Exploration of Salish Sea Tide Pools

by Adrianne Lauman, Summer 2019

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

Exploration of Salish Sea Tide Pools

By Adrianne Lauman, Summer 2019

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

A tide pool is created when a small amount of marine water is left on a shoreline or in rocky crevices when the tide recedes. The water in the rocky crevices and small pools enables the marine life to survive the low tide event until the higher tides return. Many of the intertidal seaweeds and marine life depend on the shelter of the tide pools for survival, since they cannot endure the heat from the sun and exposure to air for long periods of time. The tide pool may temporarily sustain the correct amount of light, oxygen, nutrients, temperature, space and salinity that these organisms need to live.

Every tide pool has a unique community or ecosystem of intertidal life. No organism lives in isolation and interactions constantly take place within this intertidal community. The physical environment, along with the living organisms, creates intricate connections and interactions. Within the intertidal ecosystem, each tidal zone has conditions that challenge organisms, such as: temperature differences, varying light exposure, wave action, diversity in sediments, competition, predation and variations in salinity due to freshwater sources mixing with the marine water. This impact of the physical environment is magnified even more in the context of the tide pool. Every individual tide pool acts as a micro habitat and each may have unique features based on type of rocky or sandy surface, water temperature, salinity, competition for space and access to food.

Countless ecological interactions are taking place in the tidal pools, regardless of our awareness. Fortunately, during the low tide events we are able to better observe these dramatic interactions and gain a greater awareness of the biodiversity living between the high and the low tide zones. At first glance, the tide pool may seem placid and void of life, but with careful observation one may realize there is always activity in the magical realm of the intertidal zone. Watch closely and the mysteries begin to be revealed.

A hermit crab is scavenging for decaying plant life and organisms within the rocky boundaries of the tide pool. The crab depends on the use of the marine snail shells for shelter and a protective covering. It may have to fight off other hermit crabs to claim a specific shell that it prefers. As the hermit crab grows, he or she may outgrow the shell used for shelter. The hermit crab must then search to find a larger shell to occupy (Harbo, 2011).

The grainyhand hermit crabs often select the shells of the black turban or frilled dogwinkle snails (Sept, 1999). Even the shell that the hermit requires for protection is covered in a micro ecosystem. The shell may be covered in sponges, barnacles, algae or small anemones. The sponges and barnacles filter feed on microscopic planktonic plants and animals. The barnacles are continuously opening their hard plates of armor to reveal an appendage, called cirri, that sweeps up the microscopic plants and animals for nourishment. <<see barnacle article in Issue #1>> Even the microscopic life is essential in the Salish Sea food web to provide nutrients to the marine invertebrates. Each organism has a role and a purpose to maintain harmony and balance to Salish Sea ecosystem.

Grainyhand Hermit at Kayak Point County Park in Snohomish County. Photo by Adrianne Lauman.

Frilled Dogwinkle amongst barnacles at Kayak Point County Park. Photo by Adrianne Lauman

The frilled dogwinkles, or dog whelks, are snails that feed by predation. They are able to drill into the hard plates of barnacles (Harbo, 2011). The shell of the dogwinkle snail is sometimes decorated with beautiful frilly ridges and the coloration may range from yellow to orange and even purple. The shells look like shiny jewels hidden like a treasure in rock crevices or clustered on the face of a rock.

Foulweather These Frilled Dog Whelks have been attaching clusters of egg capsules to a rock. There are numerous eggs in each capsule.

Foulweather These Frilled Dog Whelks have been attaching clusters of egg capsules to a rock. There are numerous eggs in each capsule.

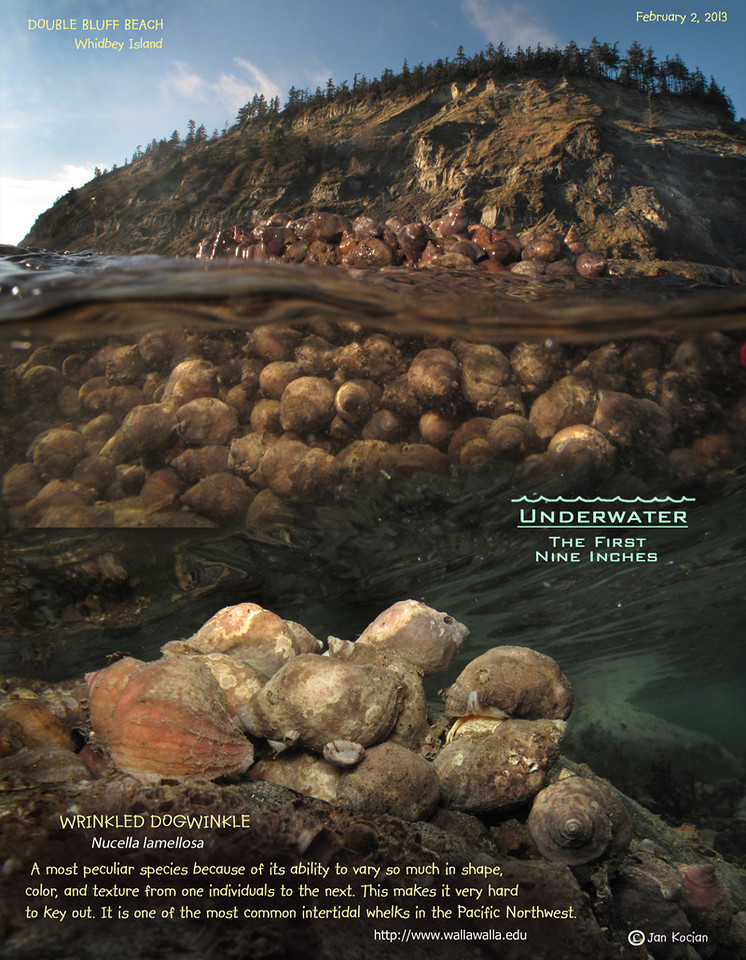

Photo by Jan Kocian

Even though the frilled dogwinkle is encased in a hard-outer shell, this marine creature is captured and eaten by red rock crabs and purple ochre sea stars (Sept, 1999). Predation and hunting for survival occurs as crabs, sea stars, tide pool fish, moon snails, anemones, marine worms, octopus, great blue herons, gulls, mink and river otters all search for other living organisms to consume in the intertidal zones. Each organism has specific adaptations to thrive in this marine world of waves, storms and predators.

Marine snails like these have a “door” or operculum that they can use to seal themselves inside their shells for protection against predators or drying out when the tide is out.

Green shore crabs, also known as hairy shore crabs, are abundant on rocky shorelines. They hide under rocks and are perfectly camouflaged in their environment with algae, rocks and sand. The shore crabs feed on sea lettuce, which is a type of green algae. Additionally, the shore crabs will scavenger feed on other small organisms.

Green Shore Crab blending into the environment at Kayak Point. Photo by Adrianne Lauman

Another amazing creature exposed by the low tide is the moonglow anemone or burrowing anemone. This anemone is usually covered in sand or small pieces of shell. The colorations may vary, but the tentacles may be a jade green with white bands. The tentacles sometimes appear to glow, resulting in the anemone’s common name of “moonglow” (Sept, 1999). The sea anemone is able to sting other organisms such as small fish and to collect plankton to feed on. Sometimes the stalk of the anemone can be seen hanging from underneath rock ledges. The moonglow anemones close in a donut shaped ring to conserve water during the low tide, as the anemones need to retain water to stay alive.

See more about a common type of anemone, including more video, photos, and poetry, in Flower of the Tide Pool in Issue #1.

See more about a common type of anemone, including more video, photos, and poetry, in Flower of the Tide Pool in Issue #1.

Each visit to the edge of a tide pool is an adventure with changing conditions and interesting marine life species to be discovered. There is much more to learn than just the common names of the marine life; a deeper knowledge may be gained by observing the life patterns and interactions that take place. The organisms have adaptations to survive harsh conditions, favorite foods to consume, and intricate interactions with other organisms.

Every marine organism has a story to tell about how it survives and the role it plays in the tide pool micro habitat. We all may access this mysterious marine world with the curiosity and enthusiasm of life long learners. Visiting intertidal sites along the shores of the Salish Sea is a rewarding pastime for people of all ages. Rachel Carson stated the following words in her appreciation for intertidal ecosystems, “Each time that I enter it, I gain some new awareness of its beauty and its deeper meanings, sensing that intricate fabric of life by which one creature is linked with another, and each with its surroundings.” (Levine, 2007)

Small octopus in the sandy sediments searching to capture prey in the tide pool created by receding tidal waters at Kayak Point. Photo by Adrianne Lauman

See an octopus finding a new home after being released after spending the Summer at the Discovery Passage Aquarium.

See an octopus finding a new home after being released after spending the Summer at the Discovery Passage Aquarium.

Adrianne Lauman spent her youth birdwatching and observing wildlife while living in Utah and Wyoming. In 2000, Adrianne graduated from Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, with a Bachelor of Science degree in biology. In 2013, she completed a post-baccalaureate teacher certification from the Department of Education at the University of Wyoming. Currently, Adrianne resides in Stanwood, Washington, where she spends leisure time hiking, birdwatching, building Lego sets and photographing wildlife. In 2015, Adrianne graduated from the Washington State University Beach Watcher beach naturalist program for Snohomish County. The opportunity to share information about the Salish Sea ecosystem and marine life has been rewarding; people are inquisitive about the region and are seeking to learn more. Adrianne recently returned from Spain, where she spent time hiking on the Camino del Norte and Camino Primitivo.

Table of Contents, Issue #4, Summer 2019

Windows On the Sea

by Nancy Sefton Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Nancy Sefton, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedI am bent over double, unable to stop a steady slide down a slope of green slime, tennies soaking, shoulders...

Star Eat Star World

by Paul Pegany Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedSome of the variety of local sea stars. Photo by Sharon PeganySome of the variety of local sea stars. Photo by Sharon PeganyBy Paul Pegany, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams...

Tide Pool Seaweed

by Sara Noland Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedPhoto by Tom NolandIt's low tide on a lovely Pacific Northwest afternoon. The beach is an expanse of rippled mud and sand, with cobbles and scattered boulders near the water’s edge. I’ve forgotten...

Sea Cucumbers

by Paul Pegany Photos & video by John F. Williams, except where notedBy Paul Pegany, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedSea cucumbers are elongated creatures with a mouth on one end and an anus on the other. They appear soft,...

Portals of Discovery

by Sharon Pegany Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedImage courtesy of Feiro Marine Life CenterImage courtesy of Feiro Marine Life CenterBy Sharon Pegany, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedAs spring gives way to...

Postscript 4

by John F. Williams Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy John F. Williams, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedThis issue marks a full year of publishing for Salish Magazine! I've learned a lot of lessons, and a...

FIND OUT MORE

Harbo, R. M. (2011). Whelks to whales. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing.

Kocian, Jan. An underwater photographer who augments his photos with artwork to add context and interpretation. His gallery The First 9 Inches Underwater is especially relevant to this Tide Pool issue of Salish Magazine

Levine, E. (2007). Rachel Carson. New York, NY: Viking Publishing.

Sept, J. D. (1999). The Beachcomber’s Guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing.

Frilled Dog Whelk (Nucella lamellosa), Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound

Moonglow anemone (Anthopleura artemisia), Sound Water Stewards, Intertidal Organisms EZ-ID GUIDES