AFTER THE RAINBOW: WHERE DOES THE RAIN GO?

Rain Gardens Help Rain Find Clean Paths to the Sea

by Sharon Pegany

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

AFTER THE RAINBOW: WHERE DOES THE RAIN GO?

Rain Gardens Help Rain Find Clean Paths to the Sea

By Sharon Pegany, Spring 2019

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

behold the notoriously wet and wild pacific northwest winter

Unrelenting atmospheric sheets of rain move eastward, trickling off roofs, clattering down rain gutters, spilling across pavement, flooding ditches and swelling streams. Inhabitants of the Salish Sea regularly witness the most efficient transportation system in the world: the water cycle. Due to their ability to change forms, water molecules are literally air-lifted from the ocean and carried as gas on the wings of the wind across hundreds of miles. Then, like mythical shapeshifters, change form again as they are cooled into liquid rain or crystalized snow. We are dependent on this cycle for the health of forests, inland water systems, wildlife, and our own water supply.

Most veteran Northwesterners feel sweet relief when such watery excess conveniently disappears down storm drains and roadside ditches, into streams and creeks, then ultimately into the Salish Sea. Over time, communities have designed clever ways to keep rain from inundating our towns and cities with engineered systems of drains, culverts, and reservoirs often referred to as “grey” infrastructure. However, keen observers notice far-reaching changes in the health and vitality of the environment and in our food and water supplies. When researchers search for potential reasons for these changes, they are invariably led to the same major culprits, one of which is the downside of our efficient rainwater drainage systems: storm water runoff.

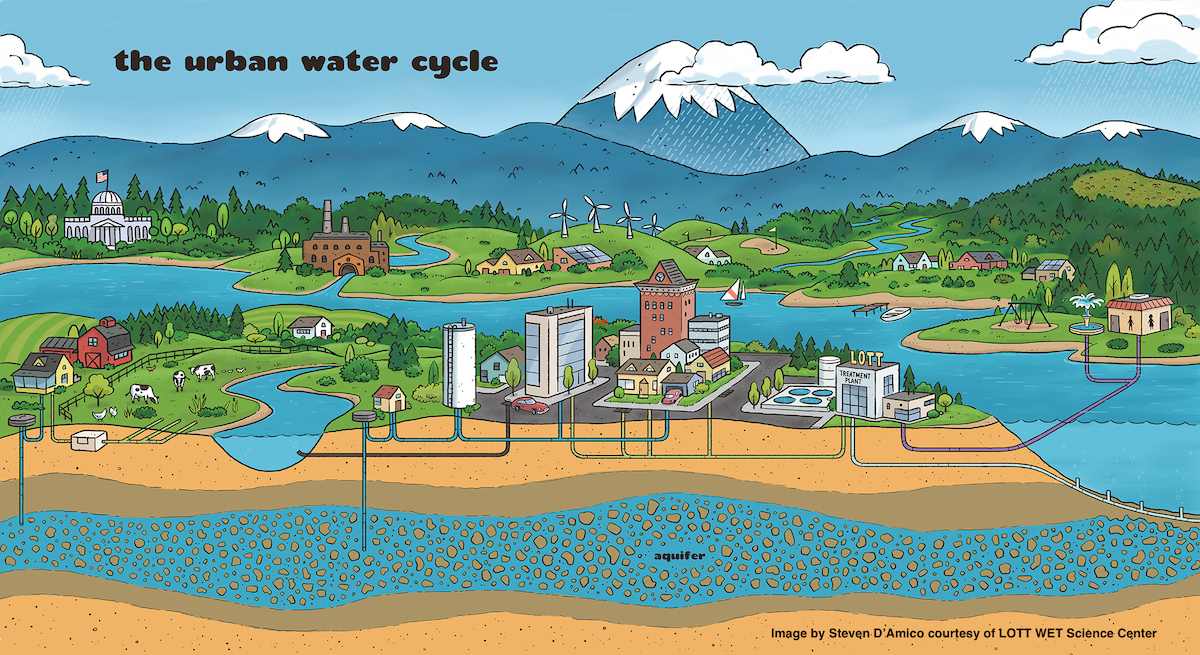

In populated settings, the water cycle is much more complicated than rain simply watering plants and then infiltrating into the aquifer and flowing in streams. This illustration shows some of the other processes, such as wells, septic systems, a sewage treatment plant, storm water, and even purple-pipe reclaimed water being used for a fountain and restrooms. Below is a discussion of various destinations for storm water. For the other topics, visit the Lott WET Science Center.

the stormwater domino effect

In its natural cycle, rain water relies on permeable surfaces like soil, gravel, and other porous matter in order to slowly soak into the ground. As water infiltrates layers of soil, it is filtered of impurities as it delivers moisture to the knobby roots of thirsty plants and trees. Eventually, this newly purified water recharges the aquifers deep below the surface. In the US, about 25% of rainfall becomes groundwater. Underground aquifers are a primary, and in some areas the only, source of drinking water. In most cases, rainfall is the only means by which critical groundwater stores are replenished.

Image courtesy of USGS Water Science School

As our communities grow, adding more homes and businesses, the amount of impervious surface such as rooftops, roadways, and parking lots also grows with its attendant fast runoff into the Salish Sea. As a result, an increasing amount of our precious rain water never stands a chance to percolate into the ground. Researchers in western Washington found that in undeveloped natural areas, surface water runoff is often less than 1%, whereas in areas impacted by development, approximately 30% of surface water tumbles undeterred to the sea.

This short video discusses some of the impacts of development on local streams.

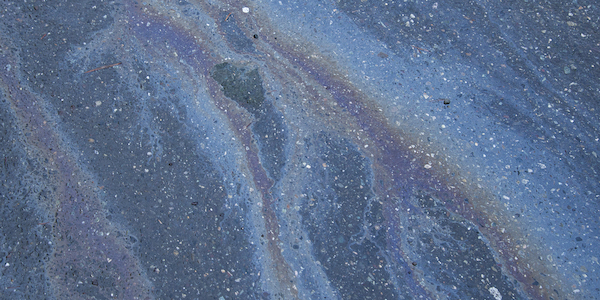

The resulting domino effect negatively impacts both aquatic and terrestrial environments, including the fish we eat and the water we drink, as well as forests that contribute to air and environmental health. According to Washington’s Department of Ecology, storm water runoff carries primarily dirt, oil, grease, nitrogen containing compounds, and phosphorus. Smaller amounts of potentially toxic chemicals such as lead, mercury and copper also flow into the Salish Sea, causing changes we are only beginning to understand. Pollutants carried by stormwater runoff are also usually responsible for closed shellfish areas and recreational beaches.

Photo by Darkday, (CC BY 2.0)

Literally everything that is on the ground can easily end up in our waterways when carried off by runaway rainwater. From cigarette butts and chewing gum to plastic bags and straws, fast moving water picks up all manner of stray objects. Even more sinister is the toxic chemical brew that results when water slurps up pathogens and bacteria from pet waste, gasoline, oil, heavy metals, tire particles, fertilizers, and sediments. It is estimated that over 10,000 different chemicals can be found in roadway stormwater, most of them non-toxic, but some severely damaging to wildlife populations such as coho salmon. (see Driving our Way to Coho Decline)

See Driving Our Way to Coho Decline in this issue.

See Driving Our Way to Coho Decline in this issue.

a dirty solution

So if excess stormwater runoff is a big factor when it comes to flooding, erosion, water supply, and pollution challenges, what can be done to help rain soak into the ground as it should as well as reduce contaminants and pollution before it reaches waterways?

See more about erosion in Soil Pedestals in this issue.

See more about erosion in Soil Pedestals in this issue.

Once again, the secrets of nature provide an answer — soil. Often overlooked as just a dirty stabilizing structure upon which we live, move, and grow crops, soil is also a powerhouse for processing and cleaning water. By slowing the flow of water, directing it away from buildings to natural areas or mimicking the activity we observe in meadows and wetlands, we can greatly reduce the current detrimental effects of stormwater runoff and ensure a healthy water table as well.

Rain Garden at Kitsap Conservation District

Based on what we are learning about the powerful properties of soil, there is a growing movement to use that knowledge to replace the “grey” infrastructure of concrete components with green stormwater infrastructure (GSI). The good news is every citizen can participate. One GSI concept that is gaining traction nationwide is the installation of rain gardens in private yards and community spaces.

A rain garden is a small, sunken landscape area that rapidly collects, absorbs, and filters stormwater runoff from roof tops, driveways, patios, and other hard surfaces that shed water quickly. Simply by capturing rainwater and releasing it back into productive soil, we can each do our part to keep some water off of our roads and impermeable surfaces, drop by precious drop. The US Department of Agriculture published a short list of the benefits of rain gardens. For starters, they are relatively inexpensive as well as easy to install and due to their design, absorb about 30% more water than conventional lawns.

Food for Thought: Potential Benefits of Rain Gardens

- Protect streams, ponds, and coastal waters

- Remove standing water in your yard

- Increase beneficial insects that eliminate pests

- Reduce potential of home flooding

- Create habitat for birds & butterflies

- Survive drought seasons

- Reduce traditional yard maintenance

- Enhance property value

the dark side: can rain gardens cause more problems than they solve?

As with all changes to the natural landscape, it is important to consider the results of our actions over time. Some researchers wonder if rain gardens can become mini toxic waste sites within neighborhoods as contaminants accumulate. When measured by sheer weight, most contaminants moving through residential areas include mostly dirt, oil, and organic matter, but there are small amounts of more dangerous substances that sneak in, such as chemicals commonly found in consumer products like lotion and soft plastics. Some studies indicate that traces of heavy metals that find their way into residential rain gardens are captured in the mulch layer.

Sightline Institute in Seattle investigated concerns and found that due to the plant and microorganism activity in soil, the biodegradation process happening in rain gardens actually destroys many contaminants rather than just storing them. (See Rain and Soil: Partners in Sustaining Life).

It is also important to understand the limitations of rain gardens. For instance, appropriate rain garden placement is critical. If placed near a bluff, infiltrating water can destabilize bluff soil and accelerate erosion. If constructed too close to the water table, water will not infiltrate and may result in standing water, which is its own can of worms. Rain gardens are designed to handle moderate rainfall and are considered a supplement, not replacement, for adequate drainage and should include accommodations for overflow. It is wise to consult with local rain garden mentors to evaluate your space. Many communities offer assistance and resources to help residents get started.

General consensus overwhelmingly considers the benefits of rain gardens outweighing any concerns, but it is a discussion that will continue as communities search for creative ways to address environmental challenges. In the meantime, rain gardens should be regarded with common sense. They are beautiful, hard-working landscape features, not designed to grow edibles or serve as sandboxes for children.

Although the Strait of Georgia has been abbreviated to the Bay of Georgia due to space constraints, can you find your home in the living Salish Sea rain garden below?

12,000 rain gardens

Ready to jump in? Designing and constructing a rain garden can be a wonderful family or community activity. It provides an opportunity to dabble in garden design and experimentation in a smaller space. Involving children in the process exposes them to many useful skills and gives them a living, changing, earth-friendly experiment to monitor right in their own yard. (For more about involving children, see the 2 videos at the end of this article)

There are hundreds of books and websites on the subject of rain gardens that basically guide homeowners through four steps: planning, building, planting, and maintaining. One valuable guide for beginners is the Rain Garden Handbook for Western Washington. Washington State University Extension and Stewardship Partners have joined forces to see 12,000 rain gardens installed in the Puget Sound area. Their site 12000raingardens.org is a treasure trove of real time information, including workshops, grant information, and other valuable resources as well as maps that plot existing residential and commercial green infrastructure sites throughout the Puget Sound area. Their goal is to map 12,000 rain gardens spread across the lower Salish Sea watershed. Read the stories of “rain gardeners” across Puget Sound and view their projects at 700 Million Gallons or Sound Impacts. The Capital Regional District in Victoria, B.C. provides many resources on their website, including a list of rain garden examples to visit in the area.

The next time you notice rain flowing along the highways and byways of your daily sphere, ask yourself where it has been and where it is going. Be on the lookout for rain gardens and bioswales and take a moment to stop and study their intentional design. You may even decide to become a rain gardener yourself. You would be doing your community and the Salish Sea a favor.

Here are two short videos that show how building rain gardens can help students develop an awareness of the roles that rain and stormwater play in our environment. [Warning: includes beavers and eagles]

Sharon Pegany is an educator and citizen scientist who loves to indulge her insatiable curiosity for the natural world. After teaching inside elementary classrooms for over 30 years, she now spends her days outside exploring, learning and encouraging others to wonder about sky, sea, and land through shared hikes, writing, photography and art. Wander with her through the contrasting naturescapes of desert, ocean and forest at pacificwondertracker.com

Table of Contents, Issue #3, Spring 2019

Precipitation

by Leigh Calvez, Spring 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Leigh Calvez, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedas a transplanted midwesterner, i am fascinated by the precipitation here in the pacific...

Raindrop

by Amy Roszak, Spring 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Amy Roszak, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedalthough most of us think of raindrops as tear shaped,by the time we see them falling through the...

Poems-3

Jenifer Browne Lawrence is the author of Grayling (Perugia Press, 2015), and One Hundred Steps from Shore (Blue Begonia Press, 2006). Awards include the Perugia Press Prize, the Orlando Poetry Prize, the James Hearst Poetry Prize, the Potomac Review poetry award, and...

Soil

Partners in Sustaining Life by Sharon Pegany, Spring 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedUSDA Public DomainUSDA Public DomainPartners in Sustaining Life By Sharon Pegany, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where...

Soil Pedestals

by Greg Geehan, Spring 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedEarly Indicators of Erosion By Greg Geehan, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedwhat does the rain hit?Rain nurtures Salish forests, and the forest...

Coho

by Paul Pegany, Spring 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted By Paul Pegany, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted can rain gardens help save salish sea coho salmon?The answer is a definite…maybe. One hidden...

Currency

by Ron Hirschi, Spring 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Ron Hirschi, Summer 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedKITSAP COUNTY SUPPORTS A FAIR NUMBER OF YEAR-ROUND STREAMSUnlike most other western Washington...

FIND OUT MORE

12,000 Rain Gardens in Puget Sound

Capital Regional District in Victoria, B.C.

Kitsap Conservation District offers technical assistance to landowners to help improve property resource management.

LOTT WET Science Center in Olympia, WA offers interpretive exhibits and events relating to water, water conservation, the urban water cycle story, wastewater treatment, reclaimed water, and protecting Puget Sound.

Rain Garden Handbook for Western Washington

USGS Water Science School, more about groundwater