the magic of evergreens

by Sarah Ottino, Winter 2023

Landscape showing the contrast between evergreens and colored deciduous leaves. photo by Sarah Ottino

the magic of evergreens

by Sarah Ottino

Winter 2023

For many, the term “evergreen” invokes images of fir-covered hills veiled in misty clouds or nostalgic memories of winter holidays. While evergreen trees are abundant in cooler parts of the hemisphere, these species are only a portion of the evergreen plants found across the globe.

The name itself offers a basic definition of this botanical category; they are plants that are always green, but there can be misconceptions about what is and is not an evergreen. Confusion arises when a plant is assumed to be an evergreen based on its appearance rather than how it functions. Some helpful botanical definitions are:

- Evergreen: a plant that retains its leaves through the year and into the following growing season

- Deciduous: a plant that sheds its leaves for a part of each year, remaining bare until new leaves are grown the following year

- Broadleaf: a relatively flat leaf with a larger surface area

- Narrowleaf: a leaf which is needle-like or scale-like

- Conifers: a group of plants produce pollen and seeds in cones

Much of the confusion is that “evergreen” is used interchangeably with “conifer.” While the majority of conifers are evergreen, not all of them are. Examples of deciduous conifer trees are two species of larch trees which prefer the eastern slopes of the Cascade Mountains.

Inversely, not all evergreens are conifers. There is a myriad of broadleaf evergreens in the Pacific Northwest, such as the Pacific madrona tree (Arbutus menziesii) and the shrub salal (Gaultheria shallon) which are nonconifer plants with seeds (berries) for reproduction.

The leaves of evergreen plants do not last forever, but unlike deciduous plants, which drop all their leaves in a short period of time, evergreen leaves are lost in small quantities throughout the year. Some evergreens lose one-year-old leaves, while others retain the same leaves for up to ten years.

Environmental stressors, such as temperature and water availability, can lead to an evergreen plant dropping more leaves than in a lower-stress year. This yellowing of an evergreen specimen can be concerning for gardeners, but instead of ripping out a not-so-green evergreen, give it a year and see if new foliage begins to grow.

adaptation

Plants, like all other living organisms, are trying to survive. Over time, certain traits emerge that help a species survive, and those traits get passed down to the next generation. Evergreen plants are found in diverse habitats, from tropical jungles to arid deserts. Although most evergreen species share similar physical traits and physiological functions, those similarities have evolved independently to meet the plant’s needs.

Some ecosystems are dominated by deciduous plants, some by evergreen plants, yet others have a balanced mixture. All plants have the same needs to survive:

- Food: most plants use photosynthesis to convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into sugar and oxygen

- Nutrients: most plants get these from the soil

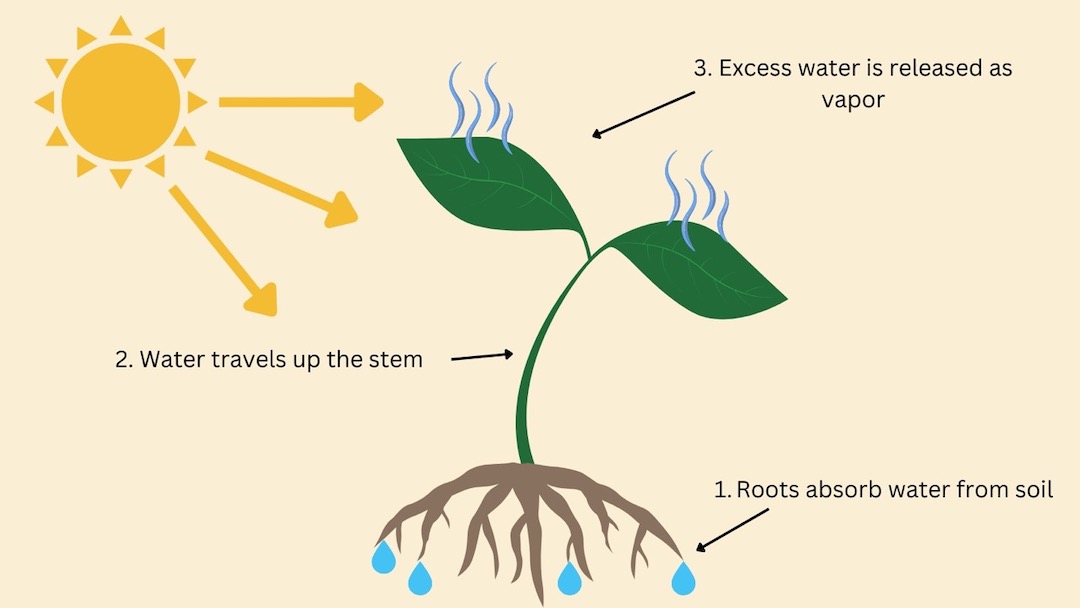

- Water: most plants take up water using their roots

However, these resources are not equally available across all ecosystems, so plants have evolved adaptations that allow them to survive with what is available.

The development of new leaves requires the use of resources. Plants that have limited resources available to them must adjust how those resources are used. Areas with abundant resources allow plants to grow larger, thinner leaves. These deciduous leaves have a short life but have high levels of photosynthesis. As sunlight and temperatures lower, the plant can afford to drop its leaves and remain dormant through the winter. The following spring, abundant resources allow the plant to regrow all new leaves.

Evergreens, however, use their limited resources more economically. Evergreen leaves have a thicker cuticle and epidermis layer, which decreases the rate of photosynthesis but lowers the amount of water lost during transpiration, making them more drought tolerant. Evergreen plants that have leaves with less surface area, such as needles, are more tolerant of shade. By dropping a smaller number of leaves throughout the year, an evergreen can photosynthesize year-round, though at lower rates than deciduous plants.

washington state’s evergreens

Washington state has four different forest regions: coastal forest, lowland forest, mountain forest, and eastside forest. Each region has unique growing conditions, allowing for a diverse assortment of plants. The greater Puget Sound/Salish Sea area is home to the lowland forest. The trees dominating this forest are Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and western red cedar (Thuja plicata), all of which are evergreen conifers. The understory is filled with evergreen shrubs such as dull Oregon grape (Mahonia nervosa), salal, and evergreen huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum).

Although the mature forest is dominated by evergreens, younger lowland forests have an assortment of broadleaf deciduous plants, including the iconic bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), red alder (Alnus rubra), vine maple (Acer circinatum), and red huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium). However, as trees grow taller, the sun-loving plants diminish, and the shade-tolerant evergreens become more abundant.

Evergreens of all kinds have cultural importance to the First Nations of the northwest coast. One of the most significant is the western red cedar (Thuja plicata), which is considered the Tree of Life by some. The use of evergreen plants for food, medicine, clothing, shelter, and transportation is innumerable. Other benefits of evergreen plants for humans include providing shade, wind buffers, and beautiful scenery. Since evergreen plants are active year-round, they are very effective at reducing air pollution and increasing soil stability, which is beneficial for all.

Autumn coloring of bigleaf maple leaves. photo by John F. Williams

See an article, a poem, and some art about bigleaf maples in our Summer 2020 issue.

See an article, a poem, and some art about bigleaf maples in our Summer 2020 issue.

ecological roles

Evergreen plants also play a vital role in the survival of other animals and plants. The marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) is a seabird that nests mainly in older, larger conifer trees. These birds are listed as an endangered species in Washington state and are greatly affected by logging. These murrelets forage for small fish in marine waters, so human impacts on these waters also affect the species.

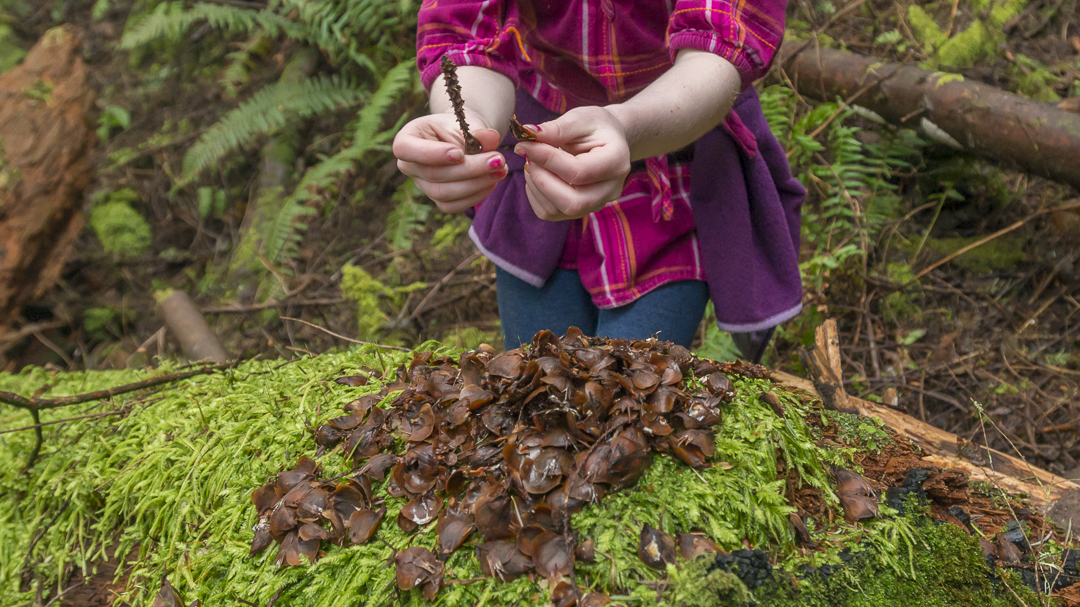

The vocal Douglas squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) makes its home in stands of evergreen conifers. Their diet is very dependent on the seeds of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), and shore pine (Pinus contorta). One can frequently find a midden pile (discarded cone scales) below their favorite tree branch; some piles accumulate over generations.

Every animal in the Salish Sea region is connected to an evergreen plant to some degree, but the importance of evergreens is not limited to animals. They can be crucial to the survival of other plants, too. Douglas-fir dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium douglasii Engelm) is a species of mistletoe that is dependent on Douglas-firs. Mistletoes are parasitic plants that live amongst the branches of the host tree. Dwarf mistletoes do not photosynthesize and receive the majority of their food and nutrients from their host.

The evergreen conifer-dominated forests of the Pacific Northwest are unique. Forests with similar climates around the world have evergreen conifers limited to extreme habitats or as early successional plants, not dominate mature species.

impacting our evergreens

Before Euro-Americans settled in western Washington, over 96% of the forests were dominated by evergreen conifers. The logging and development that came with the settlers dramatically impacted the landscape. During the past 150 years, over two-thirds of Puget Sound’s forests have been lost.

When a disturbance such as a fire, landslide, or logging destroys a mature forest, succession restarts. Sun-loving deciduous plants are the first to take root. As they grow and eventually die, they are replaced by shade-tolerant evergreens. Succession is a natural cycle that is constantly in motion. However, the more frequent disturbances are in an area, the less likely it is that the forest community will reach the mature stage.

See a photo essay about the stages a forest goes through heading toward maturity in our Winter 2018 issue.

See a photo essay about the stages a forest goes through heading toward maturity in our Winter 2018 issue.

Direct human activity, as well as human-impacted climate change, has the potential to cause lasting changes in the plant makeup of the Salish Sea region. As the summers become hotter and drier, it is more important for people to be responsible with campfires to decrease the number of human-caused wildfires. Homeowners can prioritize the health of evergreen trees on their property instead of topping them to create a better view.

Humans are a part of nature, but we have an enormous impact on the ecosystems in which we live. If we take pride in living in the evergreen state, we must take responsibility for caring for it. While Puget Sound may never regrow its evergreen forests to historic extents, we can preserve what remains and help disturbed areas regrow their evergreen magic.

FIND OUT MORE

The Diversity of Washington Forests, by Washington Forest Protection Association

Identifying Mature and Old Forests in Western Washington, Washington State Department of Natural Resources

Cedar, First Nations Studies Program at the University of British Columbia

Sarah Ottino – Freelance Writer & Photographer

I love to write, create, and explore nature. I travel full-time in a 20ft Airstream with my husband and border collie, Nimbus. I use life’s adventures as inspiration for healthy living, outdoor recreation, and environmental content. I often use my photography or design graphics to complement my writing.

Table of Contents, Issue #22, Winter 2023

Gardening With Native Evergreen Plants

by John Bolivar, Winter 2023 Snow on sword ferns. photo by John F. Williamsby John Bolivar Winter 2023The cold winter months here in the Pacific Northwest can be a lonely time — especially if some of your best friends are flowers. I start to miss my colorful...

Seeing Beyond the Trees

by Mary Johnson, Winter 2023 Evergreens in Newberry Hill Heritage Park, Silverdale, WA. photo by John F. Williamsby Mary Johnson Winter 2023Evergreen trees, particularly the Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) tree, dominate the botanical landscape on the western...

Poetry 22

by multiple poets, Winter 2023 Bare deciduous trees and evergreen trees. photo by John F. Williamsby multiple poets Winter 2023Dependable Green by Ælfhild Astrædottir Green is the call sign of summerWhen chlorophyll works overtimeGathering in wavelengths of...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.