Silent by Nature

by Tom Doty, Autumn 2023

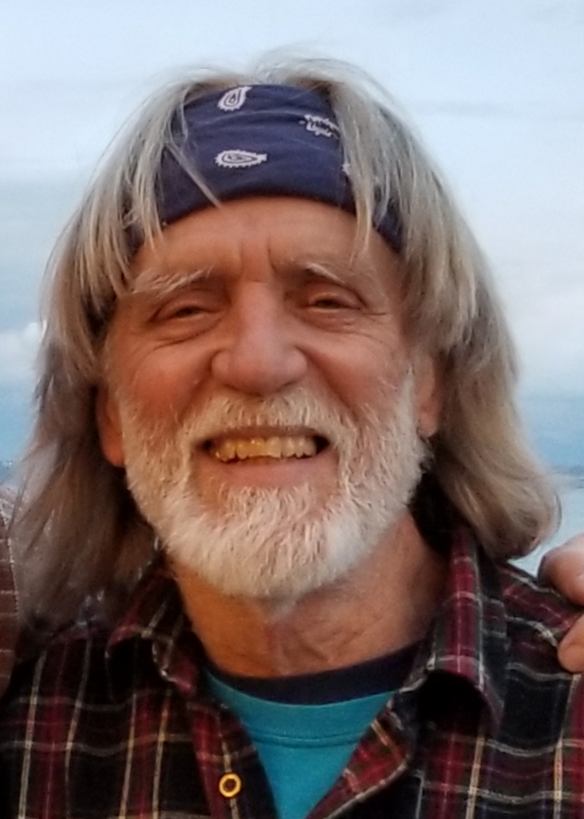

Long-toed salamander. photo by Tom Doty

Silent by Nature

by Tom Doty

Autumn 2023

Harbingers of spring, amphibians in Kitsap County include both frogs and salamanders. The iconic body form and vocalizations of frogs are familiar, but less well known are their quiet brethren, the salamanders. Like most amphibians, salamanders have a two-stage life history involving an aquatic, free-living larval stage followed by metamorphosis into a small terrestrial adult.

The Plethodontids, ‘lungless salamanders’, are the contrarians in this scheme, depositing their fertilized eggs terrestrially in damp, rotting wood and the like. Their larval stage occurs entirely within the egg. What ultimately emerges is a tiny version of an adult.

Our local aquatic-breeding amphibians reproduce mostly in late winter or early spring, commonly in small, fishless ponds and streams. Upon reaching a suitable breeding pond, male frogs advertise their location and availability for reproduction with deafening vocal choruses, thus attracting females. From our perspective salamanders appear naturally silent. Their drive to reproduce is expressed in their migratory capabilities — sexually mature adults of both sexes know where their pond is and how to get to it. We just don’t hear about it.

Frogs and salamanders have very different modes of reproduction. Most frogs, like most fishes, practice external fertilization — eggs are released into the environment and are immediately fertilized by the attendant male(s). Salamanders utilize the more flexible internal fertilization in which the female picks up a packet of sperm deposited by an attendant male and then later deposits fertilized eggs at a time and place of her choosing.

In both forms, eggs hatch, after a variable period of development, into the larval stage. In frogs, the oval, legless body and tailfin of tadpoles are well-recognized. Generally referred to as herbivorous, tadpoles spend their first days grazing on the algae that favors the egg jelly from which they just emerged (thereby recycling this important resource). Like many aquatic ‘herbivores’, tadpoles also unavoidably consume members of the smaller invertebrate herbivore community, adding an important source of protein to their diet.

In salamanders the newly hatched form is simply referred to as a salamander larva. There’s no confusing a larval salamander with a frog tadpole. The former looks like a tiny adult salamander with all four legs and a tail. The only visible larval characteristics are the feathery external gills emerging from each side of the head. Salamander larvae, like the adults they will become, are predatory carnivores, eating any animal in the pond small enough to swallow. Food consists mostly of larval and adult macroinvertebrates (aquatic bugs big enough to see), although in some cases early breeding in salamanders leads to larvae big enough to eat tadpoles of frogs breeding later in the season.

Ultimately the larval salamanders will have to leave their pond. Water levels, food and oxygen are all in decline. For amphibia in general this means it’s time for metamorphosis — the structural and functional changes required by the transition to terrestrial life. In salamanders these changes are simpler than in frogs, requiring only the resorption of the external gills, to be replaced in most, by lungs. These juvenile salamanders then disperse into the surrounding terrestrial environment, paying attention as they leave because ultimately they will need to find their way back.

Most juvenile and adult salamanders lead secretive lives, taking advantage of natural features (and occasionally human debris) to avoid predation. One group, referred to as the ‘mole salamanders’, are predisposed to utilize existing channels through the forest duff in their search for prey. Adult salamanders can wander widely in their daily activities, requiring access to an area well beyond what might be expected by their diminutive size (tens to hundreds of acres). Ultimately, however, they must find their way to a breeding pond to complete their life history activities. The logical choice, evolutionarily speaking, would be the natal pond, the one from which they successfully emerged a year or two prior. This migratory journey can be long and fraught with danger for an otherwise secretive animal. Many directional cues are available to them, including Earth’s magnetic field, and migratory pathways are known to exist in some species.

In frogs, the first to reach a suitable pond are able to advertise that fact vocally, attracting other males and, importantly, females to the party. Salamanders, having no broadcast-level voice, must depend on the navigational skills of their potential mates to find the pond and one another. Except for the brief appearance of spermatophores (the sperm packets deposited by exuberant males on the pond bottom) and the ultimate presence of egg masses we might never have known they were there.

The reproductive success of amphibians is not simply a matter of academic interest to humans. Passerine (perching) birds (about 70% of all birds) are having difficulty calcifying their eggs, one factor contributing to declining bird populations. Calcium is a common nutrient in aquatic systems but is less available terrestrially — increasingly acidic rainfall dissolves and washes it away. In times past, temporary ponds and intermittent streams produced uncountable numbers of tiny emergent frogs and salamanders carrying their calcium-rich bones into the surrounding forest where they became the opportunistic source of calcium for predatory birds and other terrestrial vertebrates. However, the decline in amphibian populations worldwide has resulted in further reductions in calcium availability terrestrially.

Global warming, in part a consequence of increasing atmospheric CO2, is perhaps the most serious long-term threat to biodiversity. In one of very few such investigations, it has recently been demonstrated that the local salamander Ensatina, by eating the bugs that eat downed wood, increase the amount of wood buried (i.e., carbon sequestered) over time by 17% in the PNW forests in which they live.

Future studies will likely reveal the degree to which other amphibians, particularly salamanders, contribute to ecosystem function. The global decline in frog populations is notable for the resulting silence. Will we notice the absence of salamanders?

Thomas Doty and his wife Aimee, a Ph.D. oceanographer at NOAA, moved to Kitsap County in 2000. With a B.S. degree in biology (cum laude) from Kent State University (1968) followed by a Ph.D. in biological sciences from the University of Rhode Island (1978), supported by the Atomic Energy Commission, Tom studied larval amphibian population dynamics.

In a postdoc sponsored by the Bureau of Land Management’s Cetacean and Turtle Assessment Program (CeTAP), Tom flew with the U.S. Coast Guard on their offshore law enforcement patrols looking for marine mammals and sea turtles in a 98,000 square mile study area in the western North Atlantic. Tom joined the faculty at Roger Williams College in 1982 and resumed his amphibian community monitoring program in Rhode Island. Following retirement, Tom studied juvenile salmon habitat preference in streams tributary to Hood Canal for the S’Klallam and Skokomish tribes, 2001-04.

Table of Contents, Issue #21, Autumn 2023

Listen To Salish Sea

by Gordon Hempton, Autumn 2023 photos and audio by Gordon Hempton except as noted by Gordon Hempton photos and audio by Gordon Hempton except as noted Autumn 2023Clap your hands, drop a pencil, set down a coffee mug — each event makes a sound — a different sound. Our...

Sound Mapping Nature

by Micaela Petrini, Autumn 2023 Misery Point, Kitsap Peninsula. photo by Micaela Petriniby Micaela Petrini Autumn 2023Do you ever spend time outside with the intent of listening? Closing your eyes, opening your ears, and taking in all of the sounds around you? This...

Singing Bullhead

by Andy Lamb, Autumn 2023 A small, recently deposited clutch of eggs with a pair of plainfin midshipman fish. One is overturned, showing its distinctive underside. photo by Linda Schroederby Andy Lamb Autumn 2023Perhaps the most colourful family...

Atmosphere

Poem and video by Renee Gastineau Autumn, 2023Atmosphere Wind and watertogether and apartcrash and crackle to sooth restless thoughts.Today and tomorrowtogether and apartconnect with the wind and waves to saymove along, take a ride, enjoy the journey, embrace the flow...

Poetry-21

Photos by John F. Williams Autumn 2023 Photos by John F. Williams Autumn, 2023Blue Skies by Nancy Taylor birds have muchto say todayeach on a different noteyet in harmony pausingwhen wind whips upto listen, to defend,or tend hatchlings no alarmingdeesfrom...

Counting Thrush Songs

by John Neville, Autumn 2023 Swainson's Thrush. photo by Janine SchuttI Decided to Find Out by John Neville Autumn 2023COVID-19 kept me at home in the 2020 springtime so I was able to enjoy the birds in my own backyard on Salt Spring Island, BC. On May 9 I first heard...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.