Transformation

by Deb Rudnick, Spring 2024

photos by Deb Rudnick

transformation

by Deb Rudnick

Spring 2024

photos by Deb Rudnick

transformation

by Deb Rudnick

Spring 2024

photos by Deb Rudnick

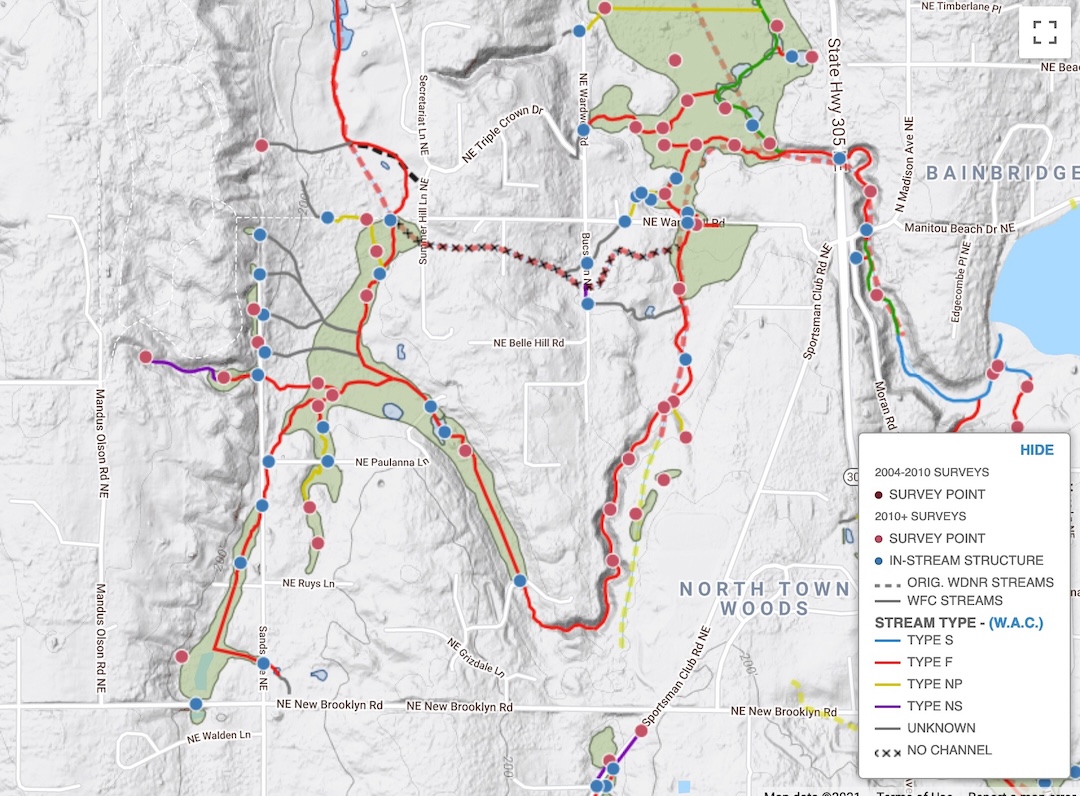

About 10 years ago, our family moved houses on Bainbridge Island, to the watershed of upper Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek, locally known also as Murden Creek, on Bainbridge Island. This creek is beautifully sinuous, draining a mostly forested watershed that covers nearly 2,000 acres (see map below). The south fork of Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek, on which I live, emerges from springs and seeps along the eastern edge of the Grand Forest Park and wetlands to its south, gathers itself into a watercourse, and begins its winding path through residential neighborhoods, including mine. It descends into a switchbacked, incised valley that runs behind two local schools before it joins with the north fork of the stream just upstream of the state highway, where it hairpin turns a few more times before it eventually flows into Puget Sound at a shallow cove.

Many Bainbridge folks know this stream by the name “Murden Creek”, which flows into Murden Cove on the east side of the Island. However, this is the Suquamish name daxwkw’d sáxwb (a Western phonetic pronunciation is “DOE-Qwap-Sah-Qwap”) which means “the place which gets jumping”. The Tribe passed a resolution in 1997 asking for this name to be retained as the official stream name by local, state and federal jurisdictions, so I will use this name here.

Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek, on the east side of Bainbridge Island. This map from the Wild Fish Conservancy’s stream typing project shows the use of the stream by fish species and many survey points. More details and pictures of the stream and fish collections can be viewed by going to:

The Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek’s watershed supports several hundred human residents and a diversity of plants, fish, and wildlife. At least three species of salmon — cutthroat, chum and coho — make their home for part or all of their lifecycle in the stream. Deer and coyotes, owls and kingfishers, songbirds and fungi live here. One of the largest spruce trees in the county, if not the state, lives here. Peat bogs live here in wetlands on the north fork. It is an astonishingly rich and beautiful ecosystem. It is such a privilege to live in this watershed, and every time I walk in it I am reminded of how beautiful it is and how, as a resident, I am responsible for treating it well.

This watershed also houses a very special resident. Hunted or trapped to near extirpation locally and throughout the region over the past two centuries, beaver are slowly reappearing in many watersheds throughout Kitsap County in places where they haven’t been seen in many years, reclaiming a landscape on which they once had a profound influence.

Beaver had come to the north fork of Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek decades ago. What I didn’t know was that beaver were soon to be our own near neighbors, as they made their way into a section of the creek close to where we live, and that I would have the incredible opportunity to watch this process unfold.

For a wonderful history of the near-extinction and more recent recovery of beaver, check out Ben Goldfarb’s wonderful book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter

For a wonderful history of the near-extinction and more recent recovery of beaver, check out Ben Goldfarb’s wonderful book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter

I. first, a creek….

If you live in this region, you may have a good picture in your mind of what a small western Washington lowland stream looks like. Forested, shaded by salmonberry and willow, small — you can probably jump across it, or walk across and barely get your ankles wet, especially in summer. That’s what Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek looked like when I’d go visit it in my neighborhood in the first few years after we moved here.

A small creek… this is at high flow, you can see some recent overbank flooding on the right side of the photo, but it is still a small creek, dark with overhanging vegetation.

A small creek… this is at high flow, you can see some recent overbank flooding on the right side of the photo, but it it is still a small creek, dark with overhanging vegetation.

I. first, a creek….

If you live in this region, you may have a good picture in your mind of what a small western Washington lowland stream looks like. Forested, shaded by salmonberry and willow, small- you can probably jump across it, or walk across and barely get your ankles wet, especially in summer. That’s what Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek looked like when I’d go visit it in my neighborhood in the first few years after we moved here.

II. then, a pond….

One day, a few years ago, I was walking one of our usual neighborhood routes with the dog, when I noticed that something was afoot. Or perhaps a-tail. Just upstream of a culverted roadway, a messy pile of branches was beginning to form in the stream. Slowly, over weeks, we watched the branches evolve into larger sticks, then logs, and soon the little wadable creek was becoming a pond.

When I first saw the dam getting underway, it struck me as a wonderful opportunity to place a wildlife camera near the dam. These cameras are relatively inexpensive, I got mine for about $100, and I can grab photos off of mine just by connecting to it with my phone. I thought it’d be fun to get pictures of a famously elusive creature. Little did I know the dramatic and beautiful events I would get to witness with this little piece of technology!

Almost immediately, I got some clues as to who was taking advantage of this slowly transforming landscape.

Mr. Barred owl was an early visitor to my wildlife camera. I wondered, was he or she here because rising floodwaters were forcing rodents out of their homes in what was formerly a stream bank?

Blue Heron was a frequent early visitor — perhaps drawn by the shallow and still relatively clear waters to look for fish and frogs?

Blue Heron liked to hang out and chat with Mr. and Mrs. Mallard. I wonder what they were discussing?

III. and back again…human transformation

But something didn’t look quite right. In the pictures above, you might notice that the bank across from the camera is quite bare, while the water level is far below it. That’s because the dam was quite a bit higher… until one day it wasn’t. Had the dam blown out in a big storm? I wasn’t sure, but I kept my camera trained, and soon I had my answer…

Someone(s) was not happy the dam was there, and they were clearly trying do something about it. Not once, but twice, over the next year or so, I captured people coming in with large rakes to remove dam material, leading to a partially destroyed dam and drained pond. Out went a lot of the water and habitat that was just starting to transform.

This dam is right upstream of a road crossing for a few houses. I could understand being very nervous about the possibility of beaver flooding the only road out. So, the homeowner’s association and I worked to bring in a number of different folks, including a habitat biologist from the state Department of Fish & Wildlife who had a look at the location and positioning of the dam to make sure it wasn’t an imminent threat to the road. We worked together to install signage, send a letter to the entire neighborhood to educate folks about the dam, and talk to folks in the neighborhood.

All our work seemed to work, for the time being, as the beaver returned once more to rebuild the dam and restart the process of transformation. Good thing they are persistent!

IV. and back again…working to conserve the dam and witnessing the transformation

Again, water began backing up into the bowl of the valley as the beaver repaired their dam. Over the following months, the cedar and alders’ leaves turned brown, and fell, as the submerged trees suffocated in this transformed system. Light penetrated the canopy, and the stilled waters began hosting duckweed and algae, floating plants that could now be supported by the slower waters and increased sunlight.

The beaver dam in late winter through summer as the canopy opens and duckweed and its photosynthesizing friends take over the pond surface

There are also many things going on underneath the surface of the water that we can’t see with a camera, but we know are happening when beavers transform these landscapes. We know from research that beaver dams affect both water quantity and quality. Beaver dams store and slow water, making it available for groundwater recharge. Their dams and the plants that form along their margins can filter and clean the water, trapping fine sediments and silts. They can also reduce the temperature of the water in the stream — a recent study in western Washington showed that water temperatures downstream of beaver ponds were nearly 5°F colder than upstream — in part due to some of that water entering the ground and cooling down before it re-emerges further downstream. That’s really important for the invertebrates and fish that depend on cold waters, especially as our streams get warmer due to development and climate change.

With these many changes from stream to pond, came changes we could see in the diversity and abundance of wildlife. Some of our heron and duck friends returned, and we had several new visitors join us as well.

Would these animals have all been here if the stream had remained a stream? Possibly, but it seems likely the open pond habitat created by the beavers was favored by many of these animals for hunting, fishing and raising their babies in and nearby.

Every time I visit the pond, I am struck by how much has occurred in such a short period of time on Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek. A few years is an ecological blink of an eye in developing food webs and community relationships. This period over which I’ve watched the dam doesn’t even register on the timescale of peat formation or meaningful changes in rates of groundwater recharge that take place over centuries to millenia. But in this little window of time, I’ve seen a glimpse of how one amazing species can begin to transform a landscape. I’ve also learned that it takes a village to support the return of a species who might be a bit uncaring of property lines and human infrastructure, and who doesn’t ask permission before moving into the HOA. As beaver return to a landscape that is far more densely and permanently populated by humans than when this species flourished centuries ago, they face many more challenges in where and how we might coexist in what we often think of as “our” streams and forests. I hope we can share and embrace, wherever possible, the remarkable transformations that beavers can provide.

Deb Rudnick, Ph.D., is an ecologist who is passionate about observing and stewarding the environment of Puget Sound. Deb received her doctorate in Environmental Science, Policy and Management from the University of California, Berkeley. Deb grew up connected to the fields, woods, marshes and meadows of New England, and slowly migrated westward, with stops in Colorado and California before setting down roots on Bainbridge Island. Deb has worked for federal, county and local governments, private industry, and has taught students from kindergarden to college. She is currently a senior scientist with EcoAdapt and the Chair of the Bainbridge Island Watershed Council, a program of Sustainable Bainbridge. Deb loves to knit, birdwatch, cycle, garden and hang out with her family and their menagerie of dog, gerbil, and chickens.

Table of Contents, Issue #23, Spring 2023

Wetlands Demystified

by Sarah Ottino, Spring 2024Wetland in Silverdale, WA. photo by John F. Williamsby Sarah Ottino Spring 2024The word “wetland” is a bit mysterious. It can evoke images of gnarled trees dripping with moss, misty mires, or serene ponds. Some people are drawn to...

Watching a Tidal Exchange

by David B. Williams, Spring 2024 photos by John F. WilliamsA stretch of beach at Discovery Park, Seattle.by David B. Williams Spring 2024 photos by John F. WilliamsThe narrow band between high and low tide is Puget Sound’s most protean ecosystem, where the rhythms...

Poetry-23

by multiple poets, Spring 2024 A mossy-branch reflection creature using a snorkel as it swims in a pond. photo by John F. Williamsby assorted poets Spring 2024 early morning rains by Sue Hylen spit splattering melodies through dry grasses & dead leaves birthing...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.