watching a tidal exchange

by David B. Williams, Spring 2024

photos by John F. Williams

A stretch of beach at Discovery Park, Seattle.

watching a tidal exchange

by David B. Williams

Spring 2024

photos by John F. Williams

The narrow band between high and low tide is Puget Sound’s most protean ecosystem, where the rhythms of existence constantly fluctuate with the twice daily expansion and contraction of our inland sea. For thousands of years, those pulses of water dictated life for the Sound’s human inhabitants. Where one lived, how one traveled, and when one could find food: all depended on knowing the tides and how they affected the movement and location of water, plants, and animals.

At present, understanding the tidal cycle of the Sound has little relevance to most residents’ lives. We no longer worry much about the timing of a full or new moon or when the tide might affect our next meal, which doesn’t mean that tides don’t still have a significance here, much of which we tend to overlook.

They affect ferry routes, loading and unloading of cargo vessels, currents, and hence navigation, and many near shore ecological processes.

That the vast majority of Puget Sound residents are unaware of the tidal rhythms is neither good nor bad. It’s simply the reality of our lives and a reflection of our overall disconnect from the natural world around us.

Hoping to remedy my disconnect, at least in a minimal way, I decided to watch a tidal exchange at Seattle’s Discovery Park. On August 10, 2017, I reached the beach at 6:30 A.M., when the water had been ebbing out for three hours. I established my base for the day, a driftwood tree trunk perfect for leaning against. A dozen feet away, beyond a sloped cobble and sand beach, quiet, barely breaking waves approached the shore so gradually they seemed reluctant to arrive. Beyond, no feature broke the smooth water surface.

High tide on that day was 11.26 feet at 3:33 A.M. and the low was -2.78 feet at 10:34 A.M.

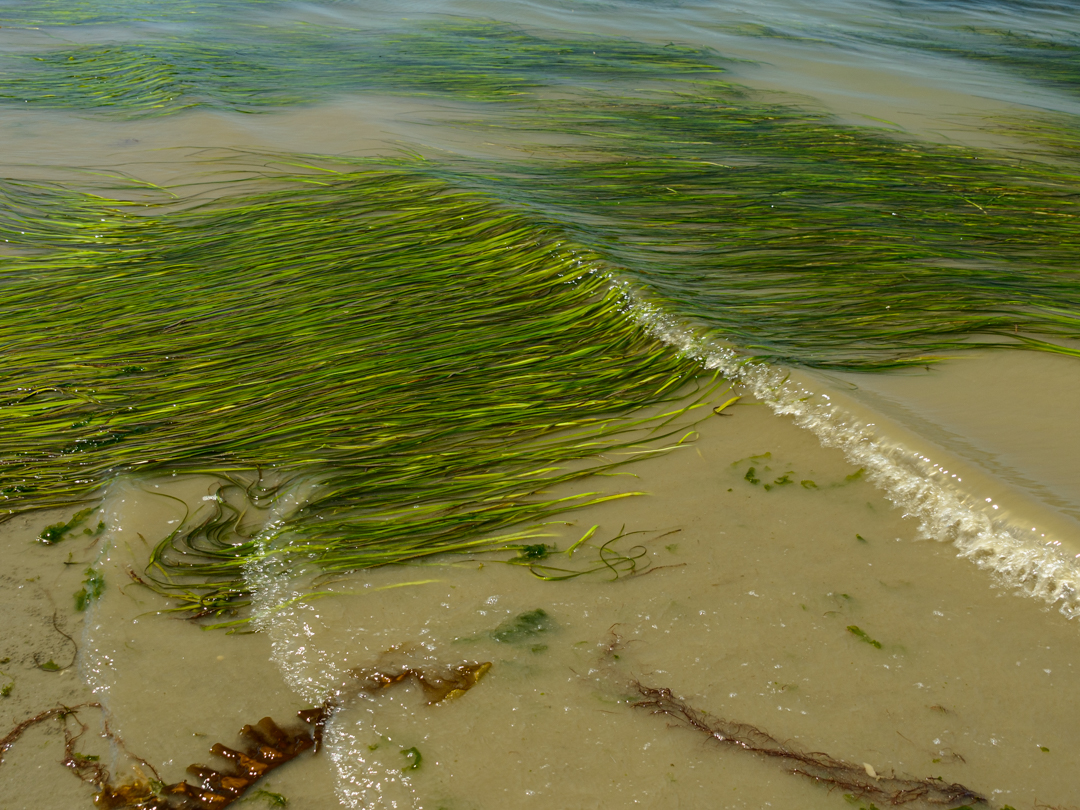

A stretch of beach at Discovery Park, Seattle.

The dominance of a liquid world would soon change as the water continued to backtrack from the sloped beach out onto a flat, low-tide terrace. By 7:00 A.M., the top of a lone boulder poked above the water surface about 65 yards offshore. Closer in, three ends of a stump had breached, and within another hour, the water had retreated enough to expose more than a dozen boulders the size of a doghouse or larger, as well as seaweed strewn fingers of cobbles and expanses of rippled sand. Further out in the water, a steady stream of kelp moved north, carried by the ebbing current.

Moon snail egg casing, shore crab, anemone in a tidepool, bull kelp, and eelgrass on the beach. You can click on image to make it full screen.

As the water retreated, I periodically left my tree trunk to explore the new world so recently hidden: barnacle-covered boulders and worm-covered barnacles; horse clam siphons and moon snail casings; crabs and crab tracks; anemones, logs, eelgrass, and kelp; ripple marks, pools, and channels; red algae and white bird poop; abandoned pier pilings and critter-filled tires; tube worm towers and weird, squiggly worm castings; great blue herons with fish in their bills and gulls with clams in their bills; squadrons of black-capped Caspian terns and a lone bald eagle harassed by gulls; and a variety of holes in the sand that I knew indicated yet another world beyond what I could see.

At the tide’s low point, at 10:34 A.M., more than a third of a mile of beach spread out into Puget Sound. I observed only minimal change over the next hour, during what is known as the tide’s slack time. Slowly the water began to advance faster, peaking between 1:30 and 2:00 P.M. During this period, I walked out to the waterline, stopped, and watched as the water swelled toward shore. Twenty minutes later, the water had risen three fourths up my calves and advanced more than 100 feet. After another thirty minutes or so, the tide had returned almost to where it had been when I arrived eight hours earlier.

A NOAA website showed that the tide changed less than a foot in the first hour. During the peak, it rose 1.59 feet in 30 minutes. Tidal aficionados adhere to the Rule of Twelfths to describe how tide change speeds up through the cycle. In the first hour, the water level changes 1/12 of the total tidal range; in the second hour, 2/12; and in the third and fourth hours, 3/12 per hour.

Watching that surge was humbling and exciting, fully revealing the tidal pulses that most Puget Sound residents, me included, fail to notice every day. Every twelve hours the Sound inhales and exhales, covering and uncovering a beautiful, evanescent world that thrives at the intersection of land and water.

Excerpted from Homewaters: A Human and Natural History of Puget Sound by David B. Williams with permission from University of Washington Press. Copyright David B. Williams.

David B. Williams is an author, naturalist, and tour guide whose award-winning book, Homewaters: A Human and Natural History of Puget Sound is a deep exploration of the stories of this beautiful waterway. He is also the author of Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography and Seattle Walks: Discovering History and Nature in the City. Williams writes a free weekly newsletter, the Street Smart Naturalist.

Table of Contents, Issue #23, Spring 2023

Wetlands Demystified

by Sarah Ottino, Spring 2024Wetland in Silverdale, WA. photo by John F. Williamsby Sarah Ottino Spring 2024The word “wetland” is a bit mysterious. It can evoke images of gnarled trees dripping with moss, misty mires, or serene ponds. Some people are drawn to...

Poetry-23

by multiple poets, Spring 2024 A mossy-branch reflection creature using a snorkel as it swims in a pond. photo by John F. Williamsby assorted poets Spring 2024 early morning rains by Sue Hylen spit splattering melodies through dry grasses & dead leaves birthing...

Transformation

by Deb Rudnick, Spring 2024 photos by Deb Rudnick by Deb Rudnick Spring 2024 photos by Deb Rudnickby Deb Rudnick Spring 2024 photos by Deb RudnickAbout 10 years ago, our family moved houses on Bainbridge Island, to the watershed of upper Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek, locally...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.