EELGRASS FLOWERING: a spring event in the Salish Sea

by Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria and Isabella Brown, Spring 2022

Seagrass Lab, Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington

Eelgrass at low tide, showing mostly flat green leaves and a yellowish, round flowering head near the center of the photo. photo by John F. Williams

Eelgrass at low tide, showing mostly flat green leaves and a yellowish, round flowering head near the center of the photo. photo by John F. Williams

EELGRASS FLOWERING: a spring event in the Salish Sea

by Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria and Isabella Brown, Spring 2022

Seagrass Lab, Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington

Those who visit beaches around the Salish Sea at low tide may be familiar with eelgrass but may not know that is a flowering plant!

While walking on, or snorkeling over, our nearshore habitats, one may even see two species of eelgrass on the same beach. Though in some places they co-mingle, eelgrass (Zostera marina) is seen lower on the beach and has longer and wider leaves. On the other hand, dwarf eelgrass (Zostera japonica), also known as Japanese eelgrass, is found higher in the intertidal and is commonly shorter and thinner. In an article later this summer we will describe in more detail the differences between the two species, and between eelgrass and other seagrass species in the Salish Sea.

Eelgrass grows from an underground rhizome anchored by fibrous roots, often forming patches or even large meadows.

In the Salish Sea, eelgrass flowering heads (also known as flowering shoots) begin to appear each year as seawater warms in early spring. Although they grow from the same underground rhizome as vegetative shoots, these flowering shoots appear for only part of the year and then die back. Most of the eelgrass visible at the beach consists of the perennial vegetative shoots, which do not produce flowers and persist year round.

This video shows the expansiveness of the eelgrass meadow during a maximum low tide at 4th of July Beach in the San Juan Island National Historical Park. video by Tom Cogan

Local residents and visitors can see informative exhibits about eelgrass on display at several locations such as the Seattle Aquarium, Padilla Bay National Estuarine Reserve, and the Port Townsend Marine Science Center.

Local residents and visitors can see informative exhibits about eelgrass on display at several locations such as the Seattle Aquarium, Padilla Bay National Estuarine Reserve, and the Port Townsend Marine Science Center.

To find some eelgrass beds near you, visit the Washington State eelgrass mapping web site.

To find some eelgrass beds near you, visit the Washington State eelgrass mapping web site.

As a more familiar example of a plant’s seasonal life cycle, imagine if you will the very visible daffodil leaves emerging from an underground bulb. As daffodils begin to grow in early spring, their bright green leaves dominate the patch, similar to a patch or meadow of eelgrass at the beach. As aboveground growth continues, the white or yellow daffodil flowers appear on special flowering stems. The daffodil flowers are more visible in the patch until they wither in the fall and die, spreading seeds that become more bulbs.

Flat eelgrass vegetative leaves on left compared with round-ish yellow branching flowering head on the right. photo by John F. Williams

Now with this image in your mind, look at the leaves of eelgrass spread out on the tideflat during a low tide in the spring. If you carefully inspect the leaves, you will see while most are flat, bright green vegetative or foliage leaves, some are more greenish yellow and are round. These are the flowering heads, and although difficult for the untrained eye to identify, after some instruction (and practice!) the difference is easily noticed.

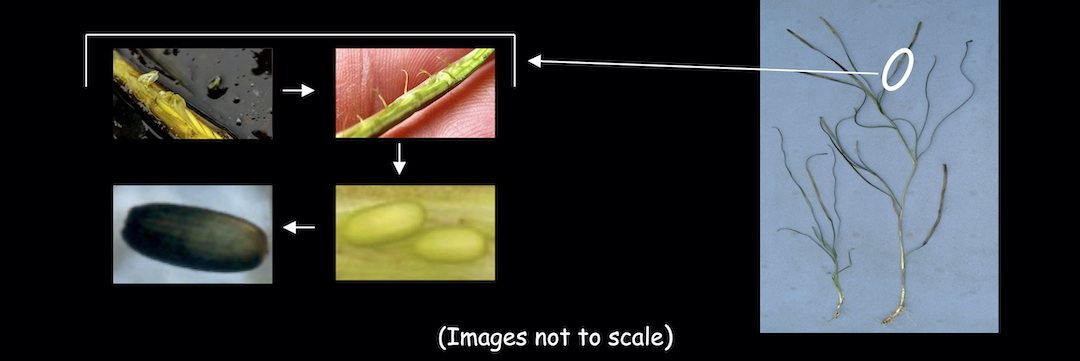

As the eelgrass flowering head grows taller, it begins to branch on the same stem, a feature that is not present in vegetative shoot development. Branching starts on the flowering stem just above the sediment, and branches grow on alternate sides of the stem upward to the top of the flowering head as shown in the accompanying photo. As the flowering head matures, spathes (the structures that enclose female and male flower parts) appear within the branches. They are quite visible during the summer low tides within the eelgrass meadow (or prairie as it called by some).

The erect stigma or female flowering part that receives pollen and receives pollen after which ovules are fertilized and seed development begins. photo by Gabriel Jacobs

The spathe is dynamic, for it is in this organ that flowers are pollinated and seed development takes place. With a careful and steady eye, one can observe pollination during sequential maximum low tide events in late spring and throughout the summer. One activity you can see is the outward expression as the female organs protrude from the spathe to receive pollen released by male organs and carried by seawater currents. This activity happens relatively quickly, and except for the protruding female organs, is rarely observed. If pollen is delivered, the ovule, now fertilized, becomes the site of seed development.

Fertilized ovules are also visible to the careful observer. Returning to the spathe, one will now notice features that appear very much like seeds because of their swollen appearance. It is exciting to know that the seed development stage is underway, and after 30 to 40 days from the appearance of female organs protruding from the spathe, the seeds are ripe.

The act of flowering captures human imagination. The seasonal appearance of a flower brings hope — hope that from life growing in the flower, a new generation will be born and life will continue.

The flowering parts of the eelgrass described above may not be easy to see at first. It helps to practice looking for them. These photos may help.

The previous photo is an example of how the light yellow flowering head appears to be cylindrical, and unlike the thin, darker green vegetative shoots, it doesn’t fall flat when slightly bent.

Next are some photos that show a flowering head from a distance (standing up), then even closer (squatting down), and then two views incrementally closer with a close-up lens. The erect stigmas or female flowering parts poking out of the spathe were seen without harming the plant.

photos by John F. Williams

FIND OUT MORE

- Eelgrass restoration work in the San Juan Islands: Generations unite to protect San Juan Islands seagrass – Seacology

- Eelgrass makes noise! https://www.eopugetsound.org/articles/voice-eelgrass

- Eelgrass diagrams and life cycle information: https://depts.washington.edu/fhl/mb/Zostera_Jess/Life%20History.html

- Technical information about eelgrass and its conservation status: https://www.eopugetsound.org/articles/eelgrass

- Washington state eelgrass mapping: https://www.dnr.wa.gov/programs-and-services/aquatics/aquatic-science/puget-sound-eelgrass-monitoring-data-viewer

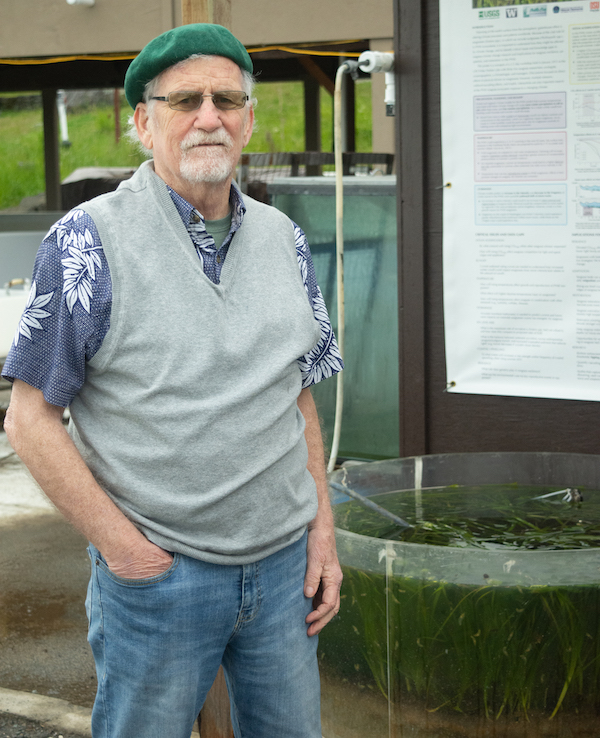

Sandy Wyllie-Echeverria: Seagrass Lab, Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington

Nearly 35 years ago, as a graduate student, Dr. S. Wyllie-Echeverria was introduced to eelgrass flowers by Dr. Paul Alan Cox on a tide flat in the San Francisco Bay. During the introduction he witnessed pollen flow from anthers to stigmas in the overlying seawater. This image captured his imagination and he decided to make the study of seagrass ecology and later seagrass ethnobotany the focus of his research. (photo by Joe Clerici)

Isabella Brown: Seagrass Lab, Friday Harbor Laboratories, University of Washington

Isabella studied Biology at Santa Clara University with minors in both chemistry and theatre. She particularly likes to work on ecology and ecosystem balance. She finds working on the Seagrass team at FHL very rewarding and energizing. Her free time is spent walking her dog Kobe or performing in local theatre productions.

Table of Contents, Issue #15, Spring 2022

The Decomposers

Video by Tom and Sara Noland Sara and Thomas Noland are naturalists who live in Everett, Washington. They live in a tiny house with many cats but are fortunate to have a big yard with lots of trees, birds, and lichens. They frequently take field trips to enjoy and...

Marine Ground Dwellers

Images by Jan KocianImages by Jan Kociansometimes worms don’t live in the ground ... especially in the Salish Sea. These curious creatures come in many forms from feathers to trumpets.moon snails and nudibranchs (sea slugs) Some of the denizens of the Salish Sea floor...

Pillbugs, Sowbugs

by Tom Noland, Spring 2022Oniscus sowbug. photo by John F. WilliamsOniscus sowbug. photo by John F. Williamsby Thomas Noland, Spring 2022Pillbugs and sowbugs are some of the small creatures you’ll commonly find on the surface of the soil. You’ll often encounter them...

I Dig Worms

by Barb Erickson, Spring 2022Nightcrawler photo by SanduStefan from PixabayBy Barb Erickson, Spring 2022I remember the iguana and the earthworm. The iguana lived in the back of the room, in a cage made of two-by-fours and chicken wire. When I say “…in the back of the...

Poetry-15

Spring 2022Salish Sea, Cama Beach Historical State Park, Camano Island, Washington.* photo by Luke VolkmannSalish Sea, Cama Beach Historical State Park, Camano Island, Washington.* photo by Luke VolkmannSpring 2022From the Ground Up by Sheryl Shapiro Venus shining...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.