Wetlands Demystified

by Sarah Ottino, Spring 2024

Wetland in Silverdale, WA. photo by John F. Williams

Wetlands Demystified

by Sarah Ottino

Spring 2024

The word “wetland” is a bit mysterious. It can evoke images of gnarled trees dripping with moss, misty mires, or serene ponds. Some people are drawn to wetlands, while others do not care for them. Many people are familiar with the terms wetland, marsh, swamp, and bog, but if you ask someone to define those terms, their response may be hesitant. The simplest definition of a wetland is an area of land saturated with water. While this definition is not wrong, neither is it fully accurate.

Wetlands are liminal zones; they are neither upland nor aquatic but a transition between them. For most people, that is all they really need to know. However, for wetland scientists and anyone fascinated by these incredible habitats, accurately defining and classifying a wetland is a bit murky.

Wetland at Watmough Bay, Lopez Island. photo by John F. Williams

determination

The word “wetland” is often used to describe any area with some water and is perhaps mucky, but there are plenty of muddy tracts of land that are not true wetlands. To qualify as a wetland, an area must meet three criteria:

- The land, for at least a period, supports hydrophytes (water-loving plants).

- The ground is mostly hydric soil (soil whose chemistry has been altered by standing water).

- The soil is covered or saturated by water during at least part of the growing season every year.

These criteria make things about as clear as mud. Determining if an area is a wetland is a bit like Goldilocks’ attempt to find the right bed. If there is too much water, it is not a wetland; if there is not enough water, it is not a wetland, but if the amount and timing of the water is just right and it has the right plants, you have a wetland.

Hydrophytic plants can survive in areas where other plants cannot. They have special adaptions that allow their roots to be constantly or seasonally submerged in water. Some adaptations include elongated stems, shallow roots, adventitious roots (roots growing from the plant’s stem/trunk), and aerenchyma (tissue that creates air pockets).

Washington State’s native yellow pond lily (Nuphar polysepala) has a large surface area to allow for photosynthesis while the rest of the plant is submerged. These water lilies also have flexible stems, which allow them to stay afloat even when the water level changes. photo by John F. Williams

The iconic western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is in the cypress family and provides an example of buttress roots, a portion of the tree’s roots that are above ground and have contact with air. photo by John F. Williams

In addition to energy, which many plants get through the photosynthesis process, plants need nutrients that are often found in the soil and taken up through their roots. When living organisms die in a forest, they break down relatively quickly, releasing their nutrients back into the soil. Wetland soils, however, are often low in nutrients. Decomposition is slow in wetlands due to low oxygen levels in the water and soil. The nutrients in the soil are taken up faster than they are replenished by decomposing organic matter. Carnivorous plants, such as the round-leaf sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), have evolved to supplement the soil’s nutrients with nutrients from flies and other small animals that they catch and digest.

In the United States, the US Army Corps of Engineers publishes the National Wetland Plant List, which is available for the whole country or by region. The guide lists plants, both native and non-native, found in the US and ranks them based on how likely they are to be found in wetlands using a code (see table). The greater Puget Sound area lies within the Western Mountains, Valleys & Coast (WMVC) region.

| NWPL Code | Meaning | WMVC Plant Example |

| Upland (UPL) |

Almost never found in wetlands |

Summer Coralroot |

| Facultative Upland (FACU) |

Usually found in non-wetlands, but may occur in wetlands |

Big-Leaf Maple |

| Facultative (FAC) |

Equally found in wetlands and non-wetlands |

Red Alder |

| Facultative Wetland (FACW) |

Usually found in wetlands, but may occur in non-wetlands |

Sitka Willow |

| Obligate Wetland (OBL) |

Almost always found in wetlands |

Broadleaf Cattail Typha latifolia |

classification

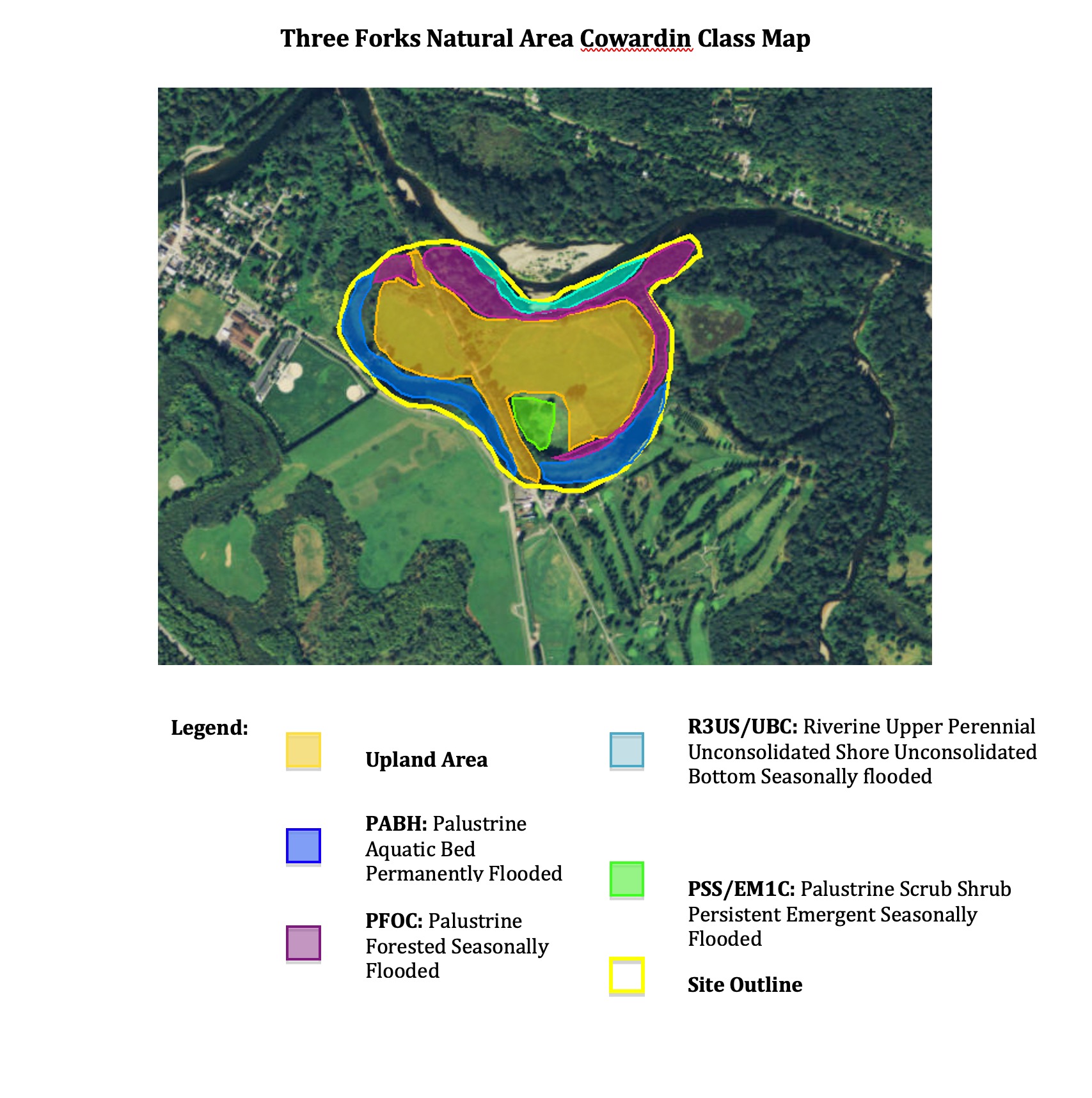

For wetland scientists, once it is determined that an area is a wetland, they must then classify it. Several classification systems exist, and not all government agencies use the same one. Here we will use the Cowardin classification system used by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It focuses on the landscape position, the type of vegetation, and the source of water.

Of course, several other classification systems exist, and not all government agencies use the same one. Another commonly used classification system is the Hydrogeomorphic (HGM) system.

Cowardin Map: A map showing the different wetland types within the Three Forks Natural Area in Snoqualmie. map courtesy of UW Wetland Science & Management Students Joy Wood, Meagan Watson, Kelly O’Callahan, and Sarah Ottino

Cowardin Classifications:

- Marine: associated with ocean coastline

- Estuarine: associated with an estuary with both freshwater and saltwater influences

- Riverine: associated with a river or stream

- Lacustrine: associated with a lake

- Palustrine: wetlands surrounded by upland where the dominant water source is rain, runoff, or groundwater

An example of a palustrine wetland is one commonly called a vernal pool. It is a depression in the bedrock or a hard clay layer that was formed during glaciation. The water source for a vernal pool is rain or runoff from the surrounding upland. Vernal pools can be found in different areas, so the vegetation varies.

Since most people are not wetland scientists, they use common terms such as swamp or marsh to classify a wetland. While these terms are not strictly scientific, they represent wetlands with certain vegetation types and/or water sources.

| Common Name | Description |

| Swamp | A wetland dominated by woody plants |

| Marsh | A wetland dominated by emergent plants |

| Bog | Dominated by moss and filled with decaying vegetation |

| Vernal Pool | Depressional wetlands |

| Fen | Similar to a bog but less acidic |

| Floodplain | A wetland that receives water when a lake or river floods |

| Seep | A wetland that forms when groundwater reaches the surface |

| Wet Meadow | Wetlands with non-woody plants such as agricultural fields |

The problem with common terminology is that not everyone uses it the same way, and it is not always the most accurate classification. For example, a wet meadow can be used in reference to a soggy field, but that field can also be called a marsh. Both a marsh and wet meadow can be classified as a lacustrine wetland with emergent vegetation.

Another example is the term swamp. A swamp can be dominated by shrubs and receive freshwater from a lake, but a swamp can also be dominated by trees and receive saltwater from the ocean, such as a mangrove swamp. Thankfully, unless you are a wetland scientist or a real estate developer, there is not much of a reason to be concerned with the proper classifications and terminology of wetlands.

rating

After a wetland has been determined and classified, it is rated. The Washington Department of Ecology has separate rating forms for Eastern and Western Washington. The assessor goes through the list, and points are assigned for the wetland classification type, type of plants present, soil characteristics, water quality function, and more. The wetland is then ranked as one of four categories:

- Category 1 Wetlands: unique/rare, more sensitive to disturbance, less disturbed, or high level of functions

- Category 2 Wetlands: difficult but not impossible to replace, or high level of some functions

- Category 3 Wetlands: moderate level of functions or can be adequately replaced

- Category 4 Wetlands: lowest level of functions and often heavily disturbed

Even though plants and animals living in the wetland, mainly threatened or endangered species, are taken into consideration, the whole extent of species supported by the wetland is not assessed. Bacteria and fungi are crucial for nutrient cycling and the breakdown of chemicals, however, neither group of organisms is considered.

wetlands for wildlife

Wetlands are sanctuaries for numerous species across all taxonomic kingdoms. They provide refuge for migrating birds and are nurseries for many juvenile species of animal. Some animals spend their whole lives in or next to wetlands, while others visit them seasonally.

The great blue heron (Ardea herodias) is just one of the countless species that are dependent on wetlands. These birds primarily eat fish but also snack on amphibians, reptiles, and small rodents. Since most of their diet is found in or near shallow water, a great blue heron would not easily survive in an upland habitat.

Broadleaf cattail (Typha latifolia) is an obligate plant species that only grows in wetlands. Red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) build their nests inside cattail leaves. Although red-winged blackbirds can be found away from wetlands, they are most abundant and seasonally dependent on wetlands with cattails.

Wetlands also provide vital habitat for fish. In the Salish Sea watershed, there are five species of Pacific salmon. While all the species utilize freshwater habitats for spawning, they do not use the exact same habitat.

|

Salmon Type |

Scientific Name |

Spawning Ground |

|

Chum/Dog |

Oncorhynchus keta |

Close to a river/stream delta |

|

Sockeye/Red |

Oncorhynchus nerka |

Lakes and streams connected to lakes |

|

Chinook/King |

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha |

Large rivers and near headwaters |

|

Coho/Silver |

Oncorhynchus kisutch |

Slow-moving water |

|

Humpy/Pink |

Oncorhynchus gorbuscha |

Small rivers and estuaries |

Dragonfly Larva: A dragonfly (Anisoptera family) larva collected from a wetland. photo by Sarah Ottino

Lacustrine wetlands provide sockeye salmon with safe hiding places and plenty of small invertebrates to eat. Riverine wetlands can provide slow-moving backwaters loved by coho. The Salish Sea itself is a massive estuary and is dotted with estuarine wetlands where all five salmon species will spend time before heading out to the Pacific Ocean.

Many people associate amphibians with wetlands, and this is not wrong, but the amount of time each species of amphibian uses a wetland habitat varies greatly. The Pacific tree frog (Pseudacris regilla), also known as the Pacific chorus frog, is quite hardy and its breeding calls can be heard even in developed areas. The frog’s eggs are laid in water, and each individual will stay there until it goes through metamorphosis. As adults, these frogs leave their nursery waters and head into upland forests, shrublands, and grasslands returning to the waters to mate.

Unlike the tree frog, the non-native American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) is more aquatic and spends its adulthood in and around wetlands. The bullfrog competes with native amphibians for habitat and is usually the successor. Thankfully, the preferred habitats of the native tree frog allow it to use seasonal wetlands, which dry up by fall and, because of that, are not home to the bullfrog

Beavers, like humans, are landscape engineers. They are so important that April 7 is International Beaver Day. Beavers do not like moving water, so much so, that the sound of running water is used as a beaver deterrent. When a beaver hears running water, they build a dam to slow it down. The creation of a dam creates a reservoir. If left undisturbed for long enough, that reservoir becomes a wetland. “Problem” beavers are sometimes relocated to areas purposely to create a wetland.

Beaver dam in Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park. photo by John F. Williams

wetland benefits

If providing vital habitat is not enough reason to appreciate wetlands, don’t worry; they have even more benefits. Coastal wetlands decrease shoreline erosion by slowing down wind and waves. Another major benefit is their ability to clean water. Wetlands are just as, if not more, effective at treating wastewater than wastewater treatment facilities, and they are cheaper. Wetlands also help mitigate climate change by sequestering carbon and other greenhouse gases.

Rough-Skinned Newt: A rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) crossing a road to access a wetland. photo by Sarah Ottino

Despite having high function and value, wetlands as a whole are sensitive. Changes in precipitation, greater coastal storms, and increased pollution strain can degrade wetlands. Historically, wetlands have been thought of as wastelands and filled in or paved over. It is estimated that around 31% of Washington State’s wetlands have been lost since the 1780s. Thankfully, we now better understand the importance of wetlands and are beginning to value them more. Buffer zones are required for building near wetlands, and mitigation is done when wetlands are impacted.

In Western Washington, wetlands are all over, and it is easy to visit parks to experience them. Here are some ways to find a wetland park to visit:

- Search “wetland” in Google Maps

- Search “wetland” in Washington Trails Association’s hiking guide

- Check with your county’s land bank/trust

- Check with your county’s and/or city’s parks department

Since wetlands provide so much for us, it’s only right that we give back. There are many ways to help protect, restore, and preserve wetlands:

- Volunteer at a work party

- Pick up litter you find on and near trails and throw it away

- Bag pet waste and throw it in the garbage

- Leave only footprints and take only memories

- Learn more about wetlands

- Teach others about wetlands

Want to learn more about wetlands? Take a look at the article FROM SWAMPS & BOGS TO MARSHES & MEADOWS in our Autumn 2020 issue.

Want to learn more about wetlands? Take a look at the article FROM SWAMPS & BOGS TO MARSHES & MEADOWS in our Autumn 2020 issue.

FIND OUT MORE

Additional Resources:

EPA: Classification and Types of Wetlands

US Army Corps of Engineers: Plant List

U.S. Fish & Wildlife: National Wetlands Inventory

U.S. Fish & Wildlife: Wetlands Mapper

WA Dept. of Ecology: Wetland Rating System

WA Dept. of Ecology: Wetlands & Climate Change

WA Dept. of Fish & Wildlife: Priority Habitats and Species List

Beavers: Wetlands & Wildlife

Seattle’s Child: 5 Wetland Boardwalks to Explore with Your Family

Sarah Ottino — Freelance Writer & Photographer

Sarah loves to write, create, and explore nature. She travels full-time in a 20ft Airstream with her husband and her border collie, Nimbus. She uses life’s adventures as inspiration for healthy living, outdoor recreation, and environmental content. She often uses her photography or design graphics to complement her writing. Her website is: www.naturewritten.com

Table of Contents, Issue #23, Spring 2023

Watching a Tidal Exchange

by David B. Williams, Spring 2024 photos by John F. WilliamsA stretch of beach at Discovery Park, Seattle.by David B. Williams Spring 2024 photos by John F. WilliamsThe narrow band between high and low tide is Puget Sound’s most protean ecosystem, where the rhythms...

Poetry-23

by multiple poets, Spring 2024 A mossy-branch reflection creature using a snorkel as it swims in a pond. photo by John F. Williamsby assorted poets Spring 2024 early morning rains by Sue Hylen spit splattering melodies through dry grasses & dead leaves birthing...

Transformation

by Deb Rudnick, Spring 2024 photos by Deb Rudnick by Deb Rudnick Spring 2024 photos by Deb Rudnickby Deb Rudnick Spring 2024 photos by Deb RudnickAbout 10 years ago, our family moved houses on Bainbridge Island, to the watershed of upper Daxwkw’d sáxwb Creek, locally...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.