INVASIVE EUROPEAN GREEN CRAB IN THE SALISH SEA:

the key to management success is community collaboration

By Leah Robison (Northwest Straits Commission) and Chase Gunnell (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Summer 2022

Large European green crab. photo by by Jonathon Hallenbeck

Invasive European green crab in the Salish Sea:

the key to management success is community collaboration

By Leah Robison (Northwest Straits Commission) and Chase Gunnell (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Summer 2022

invasive green crabs have landed in the salish sea

European green crab (Carcinus maenus) is considered one of the world’s worst invasive species. High green crab abundance can cause harm to aquatic ecosystems by decimating eelgrass habitat and outcompeting native species for resources. Green crabs are also voracious, with a broad diet that can include predation on various native and commercially important species.

Green crabs have a large native range along eastern Atlantic coastlines, from Europe to northern Africa. A type of shore crab, they are typically found in water shallower than 25 feet deep. They have been introduced globally through various means, such as unintentional transport by humans in ships’ ballast water and hiding in packing material in seafood products. Once established on a new coastline, they can spread as larvae in ocean currents.

Green crabs were found on the U.S. East Coast starting in the mid-1800s and from there spread north into Canada. In the early 1990s, European green crabs were first reported on the West Coast of the United States in San Francisco Bay. Since that initial introduction to California, they have expanded their range north along the outer coast of the western U.S. and Canada over the past few decades, typically reaching new areas as floating larvae with the help of ocean currents. Brought in by the tides, green crab larvae that have molted through several stages can then settle out of the water column into protected bays and estuaries. Here the juvenile crabs grow and molt. Inter-tidal estuary habitat is protected from several predators, including larger fish and crustaceans common in deeper waters, and is therefore favored by these crabs and provides them abundant shelter and food.

Invasive green crabs have been found on Vancouver Island and Washington’s outer coast since 1998, but the first green crab detection in the Salish Sea didn’t occur until 2012 in Sooke Basin, British Columbia. On the Washington side, they were first found in the San Juan Islands and Padilla Bay in 2016, and in Drayton Harbor and Lummi Bay in 2019. Exponential population growth at Lummi Sea Pond and on the outer coast in 2021 are cause for serious concern, but for now, most areas where green crab have been documented within the Salish Sea currently appear to only have them in low numbers. As of early 2022, invasive green crabs have not been detected within Puget Sound south of Admiralty Inlet. During a Crab Team’s monthly monitoring this May, community science volunteers discovered a green crab in Hood Canal, the furthest south these invasive crabs have been found in the Salish Sea.

Populations of invasive green crabs in the Salish Sea are currently mostly sparse and restricted to highly suitable microhabitats. Scientists believe the primarily westward-flowing surface water patterns in the Strait of Juan de Fuca act as a partial barrier to floating larvae released by established European green crab populations on the outer coast. In short, this means that outbound currents provide Salish Sea shorelines some protection from green crab larvae from coastal infestations, yet risks remain should these crabs gain a greater foothold in our region’s inland waterways.

Early detection by community members, scientists, and Washington Sea Grant Crab Team monitoring, as well as quick removal actions by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), Northwest Straits Commission, tribal governments, and partner groups have been and continue to be vital to controlling green crab numbers, preventing spread, and protecting Salish Sea ecosystems.

a vigorous invasive species with potentially large ecosystem impacts

Green crabs’ history in places like New England—where they have been able to establish large reproducing populations—shows that this is a successful invasive species. European green crabs readily adapt to new conditions, can reproduce quickly and prolifically, and can survive a range of salinity and habitat conditions. European green crabs are opportunistic omnivores, meaning they will scavenge or prey upon a wide range of foods they encounter such as shellfish, worms, snails, algae, and detritus. They can thrive in habitat types that aren’t preferred by potential competitors, like larger Dungeness or red rock crabs.

Introduced green crabs are also showing consistency with the theory that introduced species may not face the same level of natural population regulation from parasites or predators as they do in their native range. While European green crabs in their native range can be parasitized by a barnacle species that may help regulate their numbers, that parasite has not arrived (at least not yet) on our shores to infect local populations. And humans may be further assisting the green crab invasion in terms of predator escape at some local sites. One such site is the Lummi Nation’s Sea Pond, which is a contained aquaculture facility managed by tide gates that has limited access for fish and other species that might ordinarily feed on green crab larvae and molts.

Primary concerns about green crab populations establishing in the Salish Sea include impacts to eelgrass meadows and estuary habitats, which have been a major focus of regional restoration and salmon recovery efforts. Shellfish populations including oysters, clams, mussels, and native crabs are also at risk from green crab predation. Based on evidence from the eastern United States, they have had dramatic impacts by preying on other intertidal species, particularly smaller shore crabs, soft-shell clams, small oysters, and on eelgrass. One green crab can consume 40 half-inch clams a day, as well as other crabs its own size.

European green crabs could also impact Dungeness crab populations. Adult green crabs are smaller than adult Dungeness, and do not typically inhabit waters of the same depth. However, juvenile Dungeness are often found in protected intertidal areas; the same areas where adult green crabs thrive. Invasive green crabs can directly prey on juvenile Dungeness, as well as outcompete them for habitat and food.

Young invasive green crab (lower left) next to a small juvenile Dungeness crab. photo by Leah Robison

A fukui trap set among eel grass near Point Whitehorn in Whatcom County. Rock Rock crabs found their way into the trap, but no green crab were captured during this trapping effort. photo by Jonathon Hallenbeck

Invasive green crabs damage eelgrass by digging up shoots as they search for buried prey. They may also feed directly on eelgrass should other food sources be unavailable. Eelgrass is critical nursery habitat for many native Salish Sea organisms such as herring and Chinook salmon smolts.

State and tribal fish and wildlife managers, scientists, and community groups are worried that green crabs could have wide-reaching impacts on local ecosystems. The effects of green crab infestations on eelgrass and estuaries would ripple out to the shellfish and salmon, forage fish, migratory shorebirds, and humans that rely on pocket estuaries and salt marshes for protection, recreation, and sustenance.

Ultimately, if European green crabs become abundant, they pose a risk to the overall health and resiliency of the Salish Sea that could undermine many ongoing habitat restoration and species recovery efforts. The natural resources that are at risk from green crab invasion are part of the cultural identity of Indigenous Tribes and many other people of Washington. Impacts are also likely to disproportionally affect threatened and endangered species, Tribal treaty rights and First Foods, small businesses, and low-income rural communities.

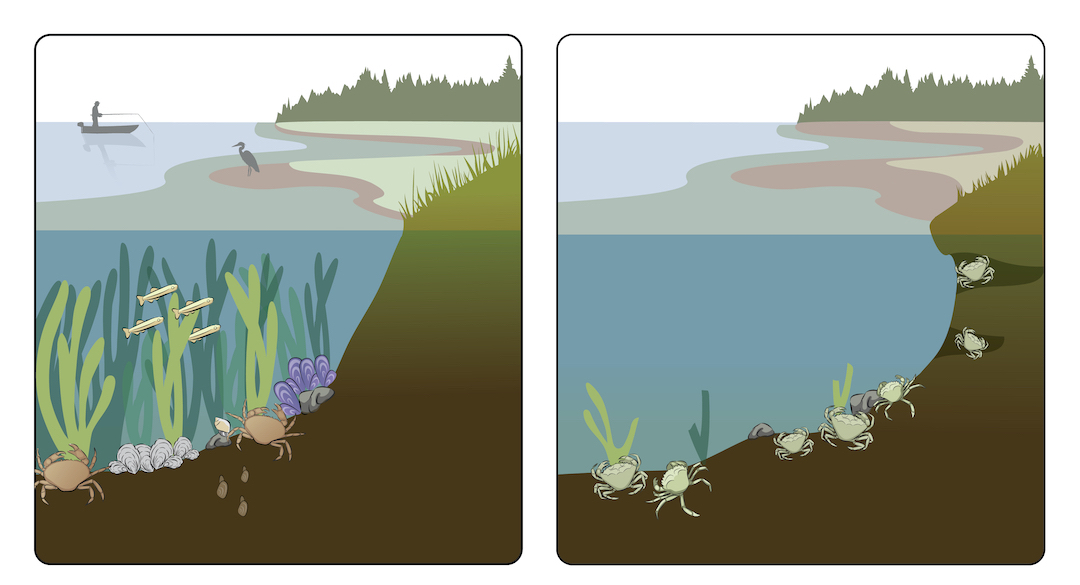

The illustrations below, by Kate Hourihan for Washington Sea Grant, show a healthy nearshore habitat on the left. On the right is shown the potential impacts if green crabs establish and become abundant in the habitat. While these many potential impacts of green crabs are not yet being documented in Salish Sea coastal estuaries, the actions we take now are critical for preventing and minimizing them (see figure).

Images provided by Washington Sea Grant. See Washington Sea Grant’s informational handout for more information.

a collaborative response

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) is the lead state agency tasked with controlling aquatic invasive species, including European green crabs. WDFW is working closely with other state and federal agencies, the Washington Invasive Species Council, universities and non-governmental organizations, and tribal nations to respond to this growing threat.

There are many pieces that fit together to manage the green crab invasion under WDFW’s lead. This includes robust early detection monitoring by community scientists at over 50 sites throughout the Salish Sea, rapid assessments and removal at new detection sites, and intensive removal efforts in localized areas with known populations. Permits and management support are available for shellfish growers or private tideland owners encountering European green crabs. Connecting with local communities on this issue is also key to reducing green crab risks.

On January 19, 2022, at the request of WDFW and tribal government, Governor Jay Inslee issued an emergency proclamation and additional funding to address the exponential increase in European green crab populations. Deployment of these funds by the Lummi Nation, Makah tribe, and local partners is well underway in the form of hiring, procurement of traps, boats and other equipment, and more boots-in-the-mud to control invasive green crabs and especially emergency infestations at sites like the Lummi Sea Pond in Lummi Bay.

Northwest Straits Commission works with Washington Conservation Crew in Padilla Bay. photo by Allie Simpson

Antonio Jones checks traps for green crab among Drayton Harbor Oyster’s shellfish growing equipment. photo by Allie Simpson

Amidst the growing concern about European green crab populations establishing in some areas of the Salish Sea, and the intensive emergency response underway by the WDFW, tribes and other partners including Northwest Straits Commission and Washington Sea Grant, there are also signs for hope.

For the past few years, a collaborative team has been trapping European green crabs at Drayton Harbor near Blaine. In 2019 a rapid response assessment pointed to Drayton Harbor as a new hotspot of a growing invasive green crab population. In 2020, a Collaborative Management Plan was developed, and substantial effort by many partners went into removing over 250 crabs from the small harbor. Capture rates declined between 2020 and 2021, indicating the response was effective at controlling the spread of green crabs within the harbor. With sound science, coordination between partners and stakeholders, and support from volunteers and the watchful eyes of beachgoers, we can control European green crab infestations in the Salish Sea before they have major impacts on native ecosystems. The progress and community collaboration in Drayton Harbor is now a model that responders in the fight against invasive European green crabs hope to follow as efforts scale up across the Salish Sea.

Closeup of green crabs. photo by Allie Simpson

how you can help

The best way for community members to help prevent expansion of the species in the Salish Sea is to be the ‘Eyes-on-the-Beach’ as you spend time along the coastline. The best places to look for evidence of European green crabs are intertidal areas with protective structure like vertical banks, intertidal vegetation, or hard debris such as shell, riprap and pilings, or logs.

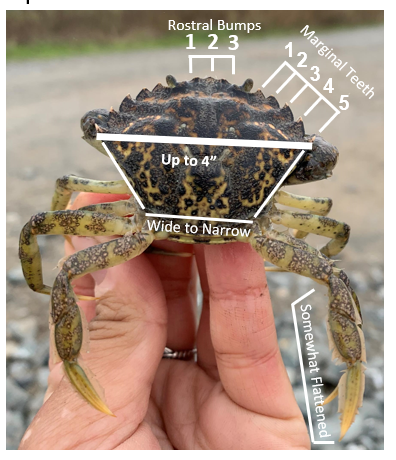

How do you know if you found an invasive green crab and not one of the many other native Salish Sea crab species? Count the spines! If it is a green crab, it will have five spines on the outside of each eye. An easy way to remember this is the word G-R-E-E-N has five letters for the 5 spines on the side of the shell of an invasive green crab. The hairy shore crab has three spines and Dungeness crabs have 10 spines on each side of their shell. The telltale sign is not its color, as many other species of crab can be green, and invasive green crabs are not always green! They may have a multi-color mottled pattern and often have yellow-orange or a red color.

European Green Crab with clear five spines on each side and three rostral bumps in the front center. photo courtesy of Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife

See more about Identifying European Green Crab and lots of photos of native crabs for comparison at this Washington Sea Grant site.

See more about Identifying European Green Crab and lots of photos of native crabs for comparison at this Washington Sea Grant site.

If you find a suspected European green crab or its shell in Washington, please take a picture, note your location, and report it as soon as possible using WDFW’s webform or the Washington Invasive Species app, available in your phone’s app store. Currently, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is not asking the public to kill suspected European green crabs. This may sound counterintuitive, but it is intended to protect native crabs from cases of mistaken identity. Our trapping teams will follow up on reports from the community with more trapping to assess the extent of green crab presence in the area.

If you are interested in volunteering as a community scientist to help monitor and trap European green crabs, check out the Washington Sea Grant’s Crab Team, a volunteer-based early detection and monitoring program to improve understanding of native salt marsh and pocket estuary organisms, and how they could be affected by green crabs. Community involvement and collaboration among partners has been, and will continue to be, major and crucial components of protecting the Salish Sea from the invasive European green crab.

FIND OUT MORE

Zombie Crabs: why can’t we get those here? https://wsg.washington.edu/crabteam/about/newsletter/late-summer-2016/#Summer1

WDFW. European Green Crab. https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/invasive/carcinus-maenas

Leah Robison serves as the Ecosystem Project Assistant for the Northwest Straits Commission. She received her B.S. degree in Environmental Science from Drake University, and is currently pursuing her M.S. in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences through Montana State University. Previously she has worked on field research projects in Midwestern prairie and forest ecosystems, and for the water quality program in Whatcom County monitoring bacteria pollution. For the Northwest Straits Commission, she provides support and helps coordinate the European green crab and forage fish spawn monitoring projects.

Chase Gunnell is the Puget Sound Region Communications Manager for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and a life-long fisherman and shellfish gatherer. His work on European green crab communications, policy, and outreach sits on the shoulders of more than a dozen WDFW Aquatic Invasive Species staffers who’ve been on the front lines of this invasion.

Table of Contents, Issue #16, Summer 2022

Story of Knotweed

By Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022 King County Noxious Weed Control ProgramYoung late-spring knotweed on gravel. photo by Sara Price, KCNWCPBy Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022 King County Noxious Weed Control ProgramIf the timeline of Earth’s history stretched across your arm...

CWMA photos

by Douglas Crist — Issue 16, Summer 2022Friends of the Farms partnering with Island School to clear invasive species and establish native, primarily edible plants at the Bainbridge Island Native Food Forest. An educational ecosystem restoration project, building...

Double Jeopardy

The Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022Purple varnish clam. photo by John F. WilliamsThe Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022The arrival of non-indigenous people to the Salish...

Green Frog

Female green frog at county stormwater pond #147. photo by Elizabeth Springborn Melissa Fleming, Ph.D.Photos by Melissa Fleming except as notedSummer 2022The green frog (Lithobates [Rana] clamitans) is the classic frog of my East Coast childhood: often the size of...

Garden Escapees

by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah)English ivy (Hedera helix) creeps through the fence and overwhelms an intentionally planted native orange honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa).by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah) Issue 16, Summer 2022It is easy for us gardeners to pick...

Invasives and killer whales

Orca mother and child. photo courtesy of NOAATara Galuska, Governor’s Salmon Recovery OfficeChelsea Krimme and Justin Bush, Washington Invasive Species Council Summer 2022The image of a large, black-and-white killer whale jumping from the water before falling back...

Poetry-16

Summer 2022Western redcedar. photo by John F. WilliamsSummer 2022INVASION by Diane Moser Beneath my windowcedars as old as Lewis and Clarkeclimb skywardreaching for rain and morning light. They try to ignore the ivythat climbs their trunk,invasive tentacles...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.