Orca mother and child. photo courtesy of NOAA

HOW INVASIVE SPECIES THREATEN SOUTHERN RESIDENT KILLER WHALES

Tara Galuska, Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office

Chelsea Krimme and Justin Bush, Washington Invasive Species Council

Summer 2022

The image of a large, black-and-white killer whale jumping from the water before falling back down with a splash is iconic in the Pacific Northwest. There is hardly a sight greater than these beautiful creatures moving silently through the water, with the occasional blow from their breath. Called killer whales or orcas, they are dear to us in the Northwest.

While the species is found throughout the world’s oceans, the population of orcas that frequent the Puget Sound and Salish Sea, called the Southern Resident orcas, are unique. They spend several months a year in Washington’s waters on their way between California and Canada and southern Alaska. Their three family groups, known as J, K, and L pods, also have their own dialect to communicate. Unlike other orcas that dine on many kinds of fish, seals, octopuses, and other marine mammals, Southern Residents prefer salmon, and Chinook Salmon is their favorite. In fact, scientists estimate that 80 percent of their diet comes from this once plentiful fish.

photo courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (News May 14, 2015)

a population at risk

What makes them unique also has made it harder for them to survive. Today, the Southern Residents are among the most endangered marine mammals in the world. Only 74 individuals remain. In 2005, the population was listed as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act, and it is considered depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Earlier this year, a review of their recovery showed continued decline despite conservation efforts. With precipitous declines continuing, in 2018 Governor Jay Inslee created the Southern Resident Killer Whale Task Force to identify immediate actions for recovery.

The task force identified three primary reasons for the declining Southern Resident population: contamination in waterways, impacts from boats, and lack of their favorite food, salmon. This is where the importance of controlling or eradicating invasive species enters the conversation.

invasive species

For Southern Residents, three invasives species — Northern Pike, knotweed, and quagga and zebra mussels — are the biggest concerns because of their ability to harm salmon, Southern Residents’ primary food.

photo courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

northern pike

Northern Pike love to eat salmon. Illegally introduced in Montana in the 1950s, this ferocious predator moved downstream into Washington via the Pend Oreille River system. Today, Northern Pike have been found in the Pend Oreille River, the Spokane River, Lake Roosevelt, several lakes in Spokane County, and in Lake Washington.

In the right conditions, they can weigh as much as 45 pounds and live for more than 20 years. Northern Pike can eat fish up to 60 percent their length, making these ambush predators dangerous to salmon. Northern Pike also reproduce quickly: a single adult female can produce 40,000 eggs a year. While most salmon migrate to and from the ocean, facing many challenges along the way, Northern Pike stay in freshwater their entire lives, making young salmon leaving their redd and heading to the ocean easy prey. Given their size and ability to reproduce rapidly, Northern Pike can spread quickly and decimate salmon runs. If Northern Pike reach the Columbia River via the Pend Oreille River, they could gobble up the already fragile salmon populations there.

The good news is that scientists and managers know how to suppress Northern Pike and are working to keep them away from valuable salmon habitat. They’ve done this by listing Northern Pike as a prohibited species and prohibiting moving live fish. In addition, they have encouraged anglers to catch them by removing size and daily catch limits. Finally, they are studying the amount and locations of Northern Pike to control established populations.

Invasive knotweed on a gravel bar. photo courtesy of Washington Invasive Species Council

invasive knotweed

Commonly referred to as a single species, invasive knotweed is four similar, perennial, invasive species originally from Asia. Most knotweed has reddish-tinged, hollow stems that can grow more than 10 feet tall, and its leaves are alternating and heart-shaped. In the late summer to early fall, knotweed sports clusters of small blooms.

Along Washington’s rivers, invasive knotweeds expand rapidly, shading out native trees and shrubs. Native trees and plants provide a root system that can stabilize slopes and anchor the soil, preventing it from entering streams where it smothers fish spawning gravel. Knotweed’s roots are thick stems with few fine roots, making them less able to prevent erosion.

Knotweed also can clog small waterways, preventing salmon from traveling upstream. Native trees and shrubs along a streambank shade the water with their larger canopies that arch over the water, cooling it for salmon. Knotweed canopies are significantly smaller and provide less shading. Native species drop branches and leaves into the water, which provide food for the insects that salmon eat, but knotweed is less palatable to aquatic insects than native plant material.

Dedicated support for statewide knotweed removal is helping ensure that Washington and its salmon habitat remain resilient and protected from total infestation. With coordination and funding from the Washington State Department of Agriculture and Salmon Recovery Funding Board, projects are underway to stop the spread of knotweed and restore streambanks for the benefit of salmon and ultimately Southern Residents.

Quagga and Zebra Mussels

quagga and zebra mussels

While quagga and zebra mussels have not been found in Washington, they are in nearby states. These striped, fingernail-sized freshwater mussels attach to hard surfaces such as rocks, docks, boats, power and water plant pipes, and even other shellfish. They reproduce quickly (one female can produce 1 million eggs annually), block water flows, and cause costly maintenance and equipment failures. Salmon would face a devastating journey navigating fish ladders, pipes, and other structures covered with layers of razor-sharp shells.

Zebra Mussels in Kansas Lake. photo by Jason Geockle, Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks

These invasive mussels also drastically change the environment they inhabit in a few ways. They can encrust river bottoms, displacing native species that need soft sediment for burrowing, lowering food availability for salmon. Shell-encrusted gravel also would create challenges for salmon spawning. These mussels are filter feeders. A single zebra mussel adult can filter up to 2 liters of water a day, consuming phytoplankton in the process. Less phytoplankton means clearer water that allows light to penetrate further, warming the cold water that salmon need to survive. More light also allows other plants in the water to grow. As those plants decay, the critters feeding on them need more oxygen and deplete the dissolved oxygen in the water. All of this can harm salmon which need cool, oxygen-rich water to survive.

Because these tiny mussels can be transported unknowingly on boats and equipment from infested areas, the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, state agencies such as the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and local organizations like Keep it Blue Lake Chelan and the Whatcom County Aquatic Invasive Species Program have been working together to keep invasive mussels from entering our waters through boat inspection and education programs.

what you can do to help

Many agencies, organizations, and individuals are working to prevent and control harmful invasive species under the guidance of the Washington Invasive Species Council’s statewide strategy. Much is known about how to reduce the invasive species that threaten the Southern Residents, but more help is needed, and it’s help the average person can provide.

photo courtesy of Washington Invasive Species Council

Here are some simple actions to prevent the introduction and spread of invasive species:

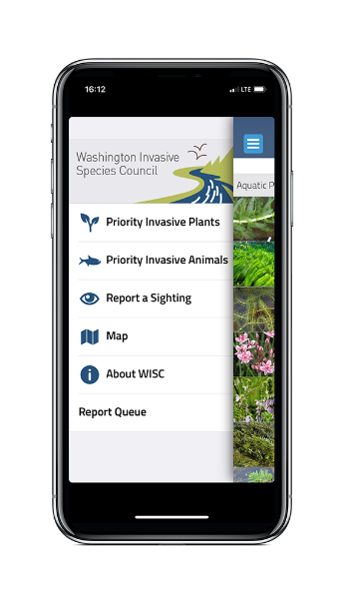

- Download the WA Invasives mobile app for a digital field guide and tool to report sightings of an invasive species while walking in your community or boating in your favorite river.

- Clean hiking boots, bikes, waders, boats, trailers, off-road vehicles, and other gear before venturing outdoors to stop invasive species from hitching a ride to a new location.

- Protect salmon by not moving any fish from one waterbody to another. This will prevent the spread of fish diseases and protect salmon from non-native, predatory fish.

- Volunteer to help remove invasive species from lands and natural areas. Contact your state, county or city parks department, land trust, conservation district, or Washington State University’s Extension Office to get involved.

- See other ways you can stop invasive species in your home.

Invasive species entering Washington affect everything from the smallest phytoplankton to the enormous Southern Residents. Northern Pike, invasive knotweeds, and quagga and zebra mussels are just three of many threats facing salmon and Southern Residents. The work to protect Southern Residents is complex, intertwined with other wildlife, and will take everyone doing their part to curb the impacts of invasive species if we are to ensure that the jumps and dives of the beloved orcas remain a part of our lives and not just the stuff of legends.

FIND OUT MORE

southern resident killer whales

- Federal Recovery Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales

- Southern Resident Killer Whale 5-year Review

- Southern Resident Killer Whale-Species in the Spotlight Priority Actions 2021-2025

- Orca Task Force Reports: Southern Resident Killer Whale Task Force

invasive species

Tara Galuska was appointed by the Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office as the Orca Recovery Coordinator in the WA State Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO) in June 2021. Before that Tara led the Salmon Recovery Section in the RCO. She also worked on aquatic planning and science at the Washington Departments of Ecology and Natural Resources.

Tara received her Bachelor of Science degree in environmental science, policy, and management from the University of California at Berkeley and her master’s degree from The Evergreen State College in Olympia. She lived, taught, traveled, and worked overseas for several years, in Asia and Central and South America. Tara lives in Olympia with her partner and two daughters. She loves soccer, ultimate frisbee, horseback riding, backpacking, traveling, and spending time with her family.

Chelsea Krimme joined the Washington Invasive Species Council staff as the Community Outreach and Environmental Education specialist in March 2022. Originally from New Hampshire, Chelsea came west in 2013 when she joined the Washington Conservation Corps. There, she worked two years on conservation projects throughout the state before being hired as a supervisor. In that role, she trained and led crews on habitat restoration, focusing on invasive species management. Chelsea earned her bachelor of science degree from Southern New Hampshire University. In her free time, Chelsea enjoys hiking, traveling, and hanging out with her dog.

Justin Bush was hired as the executive coordinator to the Washington Invasive Species Council in 2016. Justin has been working on invasive species issues since 2008 with federal, state, regional, and local organizations including King and Skamania Counties, and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas at Austin where he managed the Texasinvasives.org statewide partnership. During these years, he has been involved in various projects to prevent, detect, and control both aquatic and terrestrial invasive species and is passionate about reducing the threat they pose to the economy, native species, and ecosystems. When not working to stop invasive species, Justin can be found kayaking, SCUBA diving, riding motorcycles, and traveling.

Table of Contents, Issue #16, Summer 2022

Story of Knotweed

By Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022 King County Noxious Weed Control ProgramYoung late-spring knotweed on gravel. photo by Sara Price, KCNWCPBy Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022 King County Noxious Weed Control ProgramIf the timeline of Earth’s history stretched across your arm...

CWMA photos

by Douglas Crist — Issue 16, Summer 2022Friends of the Farms partnering with Island School to clear invasive species and establish native, primarily edible plants at the Bainbridge Island Native Food Forest. An educational ecosystem restoration project, building...

Double Jeopardy

The Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022Purple varnish clam. photo by John F. WilliamsThe Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022The arrival of non-indigenous people to the Salish...

Green Frog

Female green frog at county stormwater pond #147. photo by Elizabeth Springborn Melissa Fleming, Ph.D.Photos by Melissa Fleming except as notedSummer 2022The green frog (Lithobates [Rana] clamitans) is the classic frog of my East Coast childhood: often the size of...

Garden Escapees

by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah)English ivy (Hedera helix) creeps through the fence and overwhelms an intentionally planted native orange honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa).by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah) Issue 16, Summer 2022It is easy for us gardeners to pick...

Poetry-16

Summer 2022Western redcedar. photo by John F. WilliamsSummer 2022INVASION by Diane Moser Beneath my windowcedars as old as Lewis and Clarkeclimb skywardreaching for rain and morning light. They try to ignore the ivythat climbs their trunk,invasive tentacles...

European Green Crab

the key to management success is community collaboration By Leah Robison (Northwest Straits Commission) and Chase Gunnell (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Summer 2022Large European green crab. photo by by Jonathon Hallenbeckthe key to management success...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.