Female green frog at county stormwater pond #147. photo by Elizabeth Springborn

the green frog

In Kitsap CountyMelissa Fleming, Ph.D.

Photos by Melissa Fleming except as noted

Summer 2022

The green frog (Lithobates [Rana] clamitans) is the classic frog of my East Coast childhood: often the size of your hand, mostly green, and visible sitting placidly on lily pads in ponds throughout eastern North America. Thus, seeing it in Kingston, Wash. in 2019 initially brought a smile to my face. The conservation biologist in me followed up just as quickly with “Uh oh, they’re not supposed to be here.” Volunteers at Stillwaters Environmental Center in Kingston had taken photos of the species in a private pond along Carpenter Creek two years previously, but it wasn’t until the landowner brought us a bucket of 19 green frogs some young visitors caught in his yard in May 2019 that we were able to attract wildlife agency attention to the discovery. Later that month, Mark Hayes, an amphibian biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), visited to collect our frogs, tour the sites in the lower Carpenter Creek watershed where we’d been hearing them, and confirmed that they were indeed introduced green frogs.

The green frog has a long history in parts of the Pacific Northwest. It was probably introduced to western North America for food, fish bait, and education tools at about the same time as its larger cousin, the American bullfrog (Lithobates [Rana] catesbeiana), and as pets starting in the early 1900s. While the bullfrog has greatly expanded its range and is considered invasive and widely viewed as a predator and competitor of native frog species throughout the west, green frogs have made much less of a splash. Outside its native range, established green frog populations have only been documented in southeastern British Columbia and southern Vancouver Island, in Stevens and Whatcom Counties in Washington, and near Ogden, Utah. Surprisingly, these populations do not appear to have expanded their ranges significantly in the last 50 years, although numbers have increased locally, particularly on Vancouver Island.

Little if any research effort has been devoted to studying introduced green frog populations to determine how they spread (or not) and their impact on native wildlife and ecosystems. Studies in British Columbia and elsewhere have documented the decline of native frog species in waterbodies colonized by introduced bullfrogs, but similar information is not available for places where the smaller, less aggressive green frog has been introduced. Nonetheless, green frogs are considered invasive in B.C. as likely competitors with native amphibians. In Washington, bullfrogs are listed as priority invasive species by the Washington Invasive Species Council (meaning they are a focus for prevention and/or control efforts in the state), while green frogs are not.

Since 2016, the non-profit Whatcom County Amphibian Monitoring Program (WCAMP) has recruited citizen scientists to conduct call surveys and report sightings of both bullfrogs and green frogs in Whatcom County. Green frogs were thought to have been introduced to Toad Lake, a few miles northeast of Bellingham, over 100 years ago. WCAMP and iNaturalist records show green frog reports all within less than 15 miles to the north, east, and west of the lake. So far, green frog reports in Kitsap County have been localized in the lower Carpenter Creek and Grovers Greek watersheds between Kingston and Miller Bay, south of a population first reported in Carpenter Lake in 2016.

WDFW advised Stillwaters on various ways to try eradicating the green frogs in Carpenter Lake and beyond, all of which are both labor intensive and likely problematic for native species, including trapping and dredging ponds. Carpenter Lake is a natural reserve and wildlife sanctuary located in the middle of a sphagnum bog and is largely inaccessible by boats that would be necessary to conduct control efforts there. After consulting with amphibian biologist Dr. Tom Doty, who had retired to North Kitsap from teaching at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island, Stillwaters decided to adopt the WCAMP approach of monitoring green frog distribution in hopes that an agency or academic researcher will be interested in conducting a study on their impact here someday.

Male green frog at county stormwater pond #147. photo by Elizabeth Springborn

The green frog situation led Tom and I to some interesting discussions because of differences in our initial levels of concern about green frogs being potentially invasive in North Kitsap. I was initially quite concerned that they could become a species “whose introduction does or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health,” as invasives are defined by the National Invasive Species Council. Tom felt that native amphibian declines due to pollution, disease, and habitat loss far outweighed potential declines due to a non-native amphibian outcompeting them and that the former were problems more deserving of our limited time, money, and attention. The more I read about introduced green frog populations in the Pacific Northwest and observed native amphibians here, the more I came to agree that green frogs, in North Kitsap at least, did not appear to be a threat commensurate with time and effort it would take to eradicate them.

Freshly laid green frog egg mass floating on surface of Kingston Hills stormwater pond #148, May 14 2021.

Many local amphibians start breeding as early as December and January, taking advantage of innumerable seasonal wetlands that appear during our winter rains, hatching as soon as water temperatures allow, and metamorphosing relatively quickly before these water bodies dry up as they typically do in late summer.

Green frogs are adapted to living in waterbodies with predatory fish (like trout in Carpenter Lake), which native amphibians breeding in more seasonal waterbodies don’t have to deal with. Like bullfrogs, they start breeding when the water is warmer, have eggs that develop relatively quickly, and have a longer tadpole or larval stage, often more than a year, before metamorphosing.

Same green frog egg mass, lifted off the bottom on May 17 2021, already hatching.

Green frogs may do well in permanent water bodies like Carpenter Lake (where no bullfrogs have been reported), but many of the stormwater and small backyard ponds they’ve also been reported in may not be able to support successful reproduction in most years. Thus, green frogs’ impacts on native species may be largely restricted to larger ponds and lakes.

Ecologists and others have observed the growing impact of non-native species on biological diversity around the world with alarm, but biologists who study invasive and potentially invasive species have come to appreciate the importance of taking an objective look at the role of non-native species in their new environments. Are negative outcomes the mostly likely result when a non-native species gains a foothold in a new location? Not necessarily. There are many examples of non-native species which have major disruptive impacts on ecosystems and decimate native species. There are also examples of non-native species that have become important in conservation efforts because they are filling a niche emptied due to local extirpation or extinction — like non-native birds in Hawaii that pollinate and disperse seeds of native plants whose survival depends on them now that native nectivores and frugivores have gone extinct. In Puerto Rico, non-native plantation trees, which are better at colonizing disturbed areas, create conditions that can facilitate the re-establishment of native trees.

Female green frog showing prominent dorsolateral folds running down both sides of her back. photo by Joe Lubischer

Non-native species are also spreading, not just by human-mediated introductions (intentional or accidental), but via range shifts tracking anthropogenic changes to the environment like deforestation, reforestation, and global climate change. Decisions about how to manage non-native species are best made on a case-by-case basis, particularly in human-disrupted environments, and the case of range-shifting species requires even more careful consideration, especially in the face of climate change.

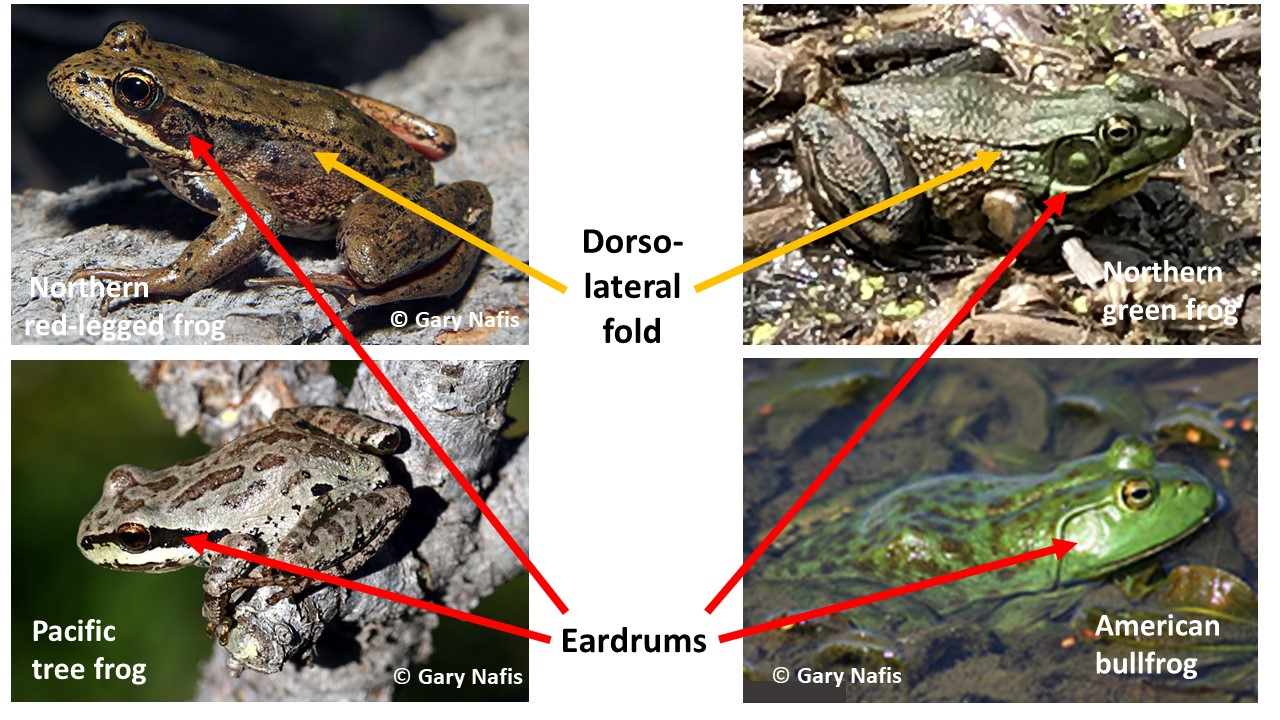

Stillwaters would appreciate your help in tracking the distribution of green frogs in Kitsap County. They are easily distinguished from native frog species (see Figure below) by their prominent eardrums (tympana) directly behind their eyes, larger than the eye in males and smaller in females. In native Pacific tree frogs and northern red-legged frogs, the eardrums are largely obscured by a dark mask extending backward from around the eyes. Prominent eardrums are also features of the green frog’s close relative, the bullfrog, which occurs in Kitsap County as well. Green frogs also have folds of skin that run down both sides of the back and bullfrogs do not. These dorsolateral folds are also found in red-legged frogs and is a good way to distinguish young red-legged frogs from brown-phase tree frogs (which can be brown or green) whose backs are smooth. Red-legged frogs can be greenish as well, so color is never a good identification criterion for local frogs.

Green frogs also have a distinctive call, most often described as a “banjo twang,” quite unlike that of Pacific tree frogs and bullfrogs. The red-legged frog’s call is a low “stutter” that is rarely heard unless one is practically standing on top of them; they often call underwater making it even harder for us to hear them.

Recordings of calls for all frog and toad species (native or not) in British Columbia (and the Puget Sound Basin) are included in excellent fact sheets for each species (click here)

Recordings of calls for all frog and toad species (native or not) in British Columbia (and the Puget Sound Basin) are included in excellent fact sheets for each species (click here)

Please report green frog calls or sightings (with photos if possible) to:

melissa@stillwatersenvironmentalcenter.org

Accepting responsibility for our role in the movement of species and the problems that result also means accepting greater stewardship and management roles in the new ecological communities we’ve created. As our responsibilities to the environment expand, managers and scientists need more help than ever from local communities to gather data needed to make decisions about how best to spend our limited time and resources managing new and established species in changing ecosystems. Citizen or community science has become an invaluable tool for collecting large amounts of quality data quickly and inexpensively. There are numerous opportunities to participate in outside projects that match your interests and passions in the Pacific Northwest.

Check out the Pacific Northwest Citizen Science web page for a partial list of local and regional projects.

Stillwaters’ volunteers and interns amphibian egg mass monitoring in Kingston Hills stormwater pond #147.

Red-legged frogs.

Melissa Fleming, Ph.D., Monitoring Director at Stillwaters Environmental Center, received the science reins from founding partner Joleen Palmer in January 2020. Melissa earned her doctorate from UW in Animal Behavior, has taught several undergraduate research courses, and did post-doctoral fellowships at University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks and at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. She subsequently worked in conservation genetics studying endemic mammals of the North Pacific coast. She’s lived in Kitsap County since 1999 with her husband, John Ellsworth. She is a life-long learner who has thoroughly enjoyed her immersion into environmental science since joining Stillwaters in early 2018.

Table of Contents, Issue #16, Summer 2022

Story of Knotweed

By Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022 King County Noxious Weed Control ProgramYoung late-spring knotweed on gravel. photo by Sara Price, KCNWCPBy Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022 King County Noxious Weed Control ProgramIf the timeline of Earth’s history stretched across your arm...

CWMA photos

by Douglas Crist — Issue 16, Summer 2022Friends of the Farms partnering with Island School to clear invasive species and establish native, primarily edible plants at the Bainbridge Island Native Food Forest. An educational ecosystem restoration project, building...

Double Jeopardy

The Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022Purple varnish clam. photo by John F. WilliamsThe Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022The arrival of non-indigenous people to the Salish...

Garden Escapees

by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah)English ivy (Hedera helix) creeps through the fence and overwhelms an intentionally planted native orange honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa).by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah) Issue 16, Summer 2022It is easy for us gardeners to pick...

Invasives and killer whales

Orca mother and child. photo courtesy of NOAATara Galuska, Governor’s Salmon Recovery OfficeChelsea Krimme and Justin Bush, Washington Invasive Species Council Summer 2022The image of a large, black-and-white killer whale jumping from the water before falling back...

Poetry-16

Summer 2022Western redcedar. photo by John F. WilliamsSummer 2022INVASION by Diane Moser Beneath my windowcedars as old as Lewis and Clarkeclimb skywardreaching for rain and morning light. They try to ignore the ivythat climbs their trunk,invasive tentacles...

European Green Crab

the key to management success is community collaboration By Leah Robison (Northwest Straits Commission) and Chase Gunnell (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Summer 2022Large European green crab. photo by by Jonathon Hallenbeckthe key to management success...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.