THE STORY OF KNOTWEED

By Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022

King County Noxious Weed Control Program

Young late-spring knotweed on gravel. photo by Sara Price, KCNWCP

THE STORY OF KNOTWEED

By Skye Pelliccia, Summer 2022

King County Noxious Weed Control Program

If the timeline of Earth’s history stretched across your arm span, the Big Bang would start at your left fingertips, the first multicellular organism would appear at your left armpit, plants would appear near your right wrist, dinosaurs would go extinct at your first right middle finger knuckle, and humans would be less than one millimeter of your pinkie’s fingernail.

Despite our relatively short existence, humans have done more to reshape earth’s living systems than most other species in history. The most invasive species on Earth is arguably Homo sapiens, and we are also the intentional and unintentional conduits of other invasive species throughout the world, particularly a vast array of invasive plants. Because we rely on plants’ nutrients for our survival, build houses with trees, and garden with a wide variety of ornamentals, we have many intimate relationships with plant species and many ways in which we move them around the world. Some were brought to a new land as relics of old homes, some as crops, and others just as ornamental greenery because, why not? This is how many invasive plant species are established in new ecosystems. But how they got here is not the only interesting part of the story– it’s why they stayed.

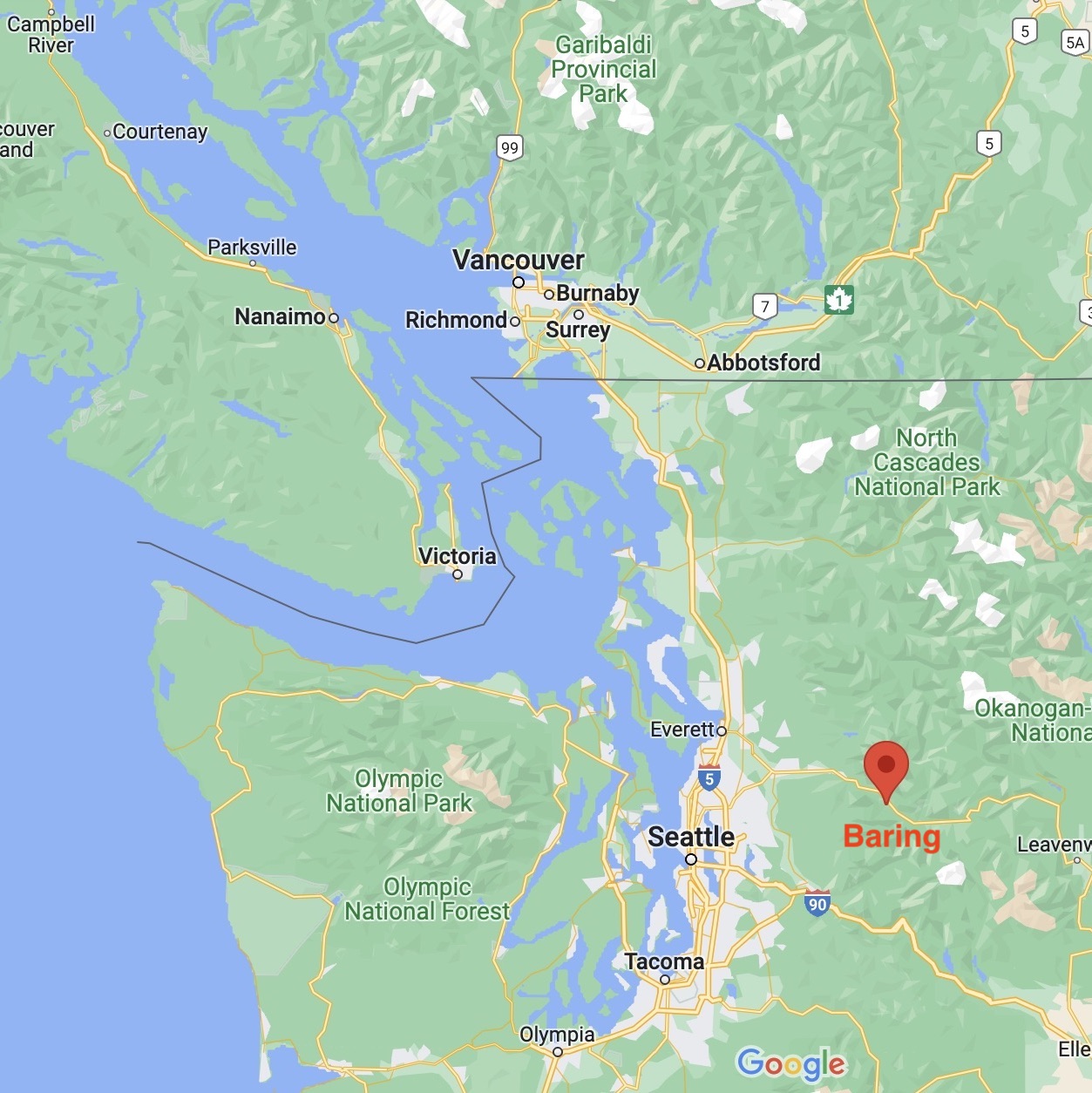

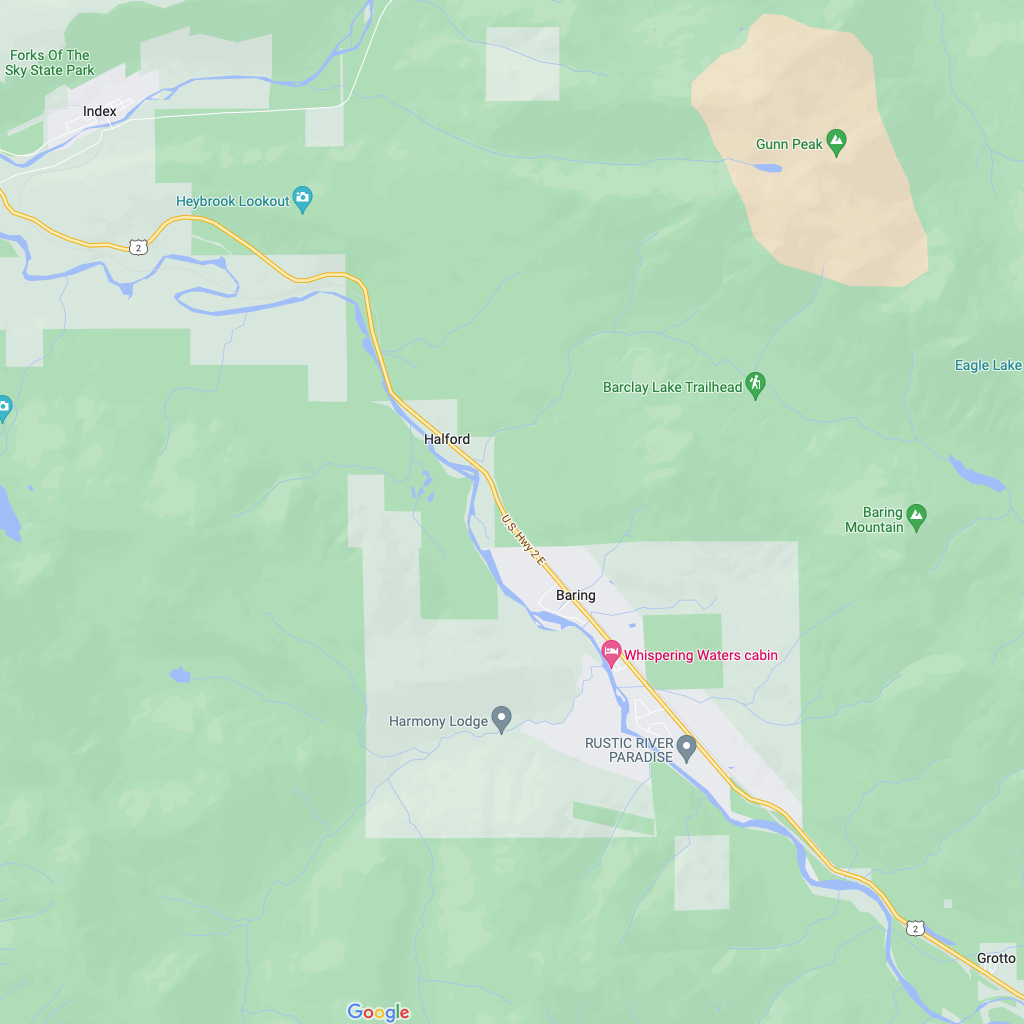

This is the story of a river valley along what is now known as the Skykomish River that was once stewarded by the sq’íxʷəbš (Skykomish) people. Let’s take a journey through time that will follow the evolution of a knotweed-laden site in the Skykomish River valley near the modern-day town of Baring, Wash.

Every weed has its story, and this story is about a weed that has arrived in this valley and is trying very hard to stay — knotweed. For our purposes “knotweed” refers to four species: Itadori knotweed (Fallopia japonica), hybrid knotweed (F. x bohemica), giant knotweed (F. sachalinensis), and Himalayan knotweed (Persicaria wallichii). But first, we need to recognize the vast history of the land and what it might have been if not for colonization and the introduction of plants that came with it.

the history of the Skykomish Valley and the arrival of knotweed

Our forests have looked the way they do for roughly 6,000 years. Walking through the forest at that time, you would look up and see the familiar deeply grooved bark of the Douglas fir and the Western red cedars.

The forest is not “untouched,” however. Rather, the sq’íxʷəbš (Skykomish) people, also known as the “upriver people” in their native tongue, are the stewards of this diverse ecosystem. When the Cordilleran Ice Sheet receded, the vast valley became a place for communities to establish as the climate stabilized.

The closest village, Xə’xaysalt, was only a few miles northwest of the town of Index, Wash. Land in the area was shared and stewarded for generations among native communities.

Before colonizer contact, communities in this area ebbed and flowed like the river they called home for around 180 generations. Family relationships determined where one could fish or gather. While the land was primarily stewarded by the sq’íxʷəbš (Skykomish), with permission, other local tribes such as the sdukʷalbixʷ (Snoqualmie) and dxʷlilap (Tulalip) forged and coexisted in the area.

The landscape was altered to meet human needs, such as burning practices to exclude trees and encourage growth of more useful plants. Fruits were foraged, game hunted, and natural materials used to make household items. The people highly regarded the land as a life-giving force that was to be honored and respected. People consumed only what was needed, depending on the season. Oral tradition gave generations location-specific knowledge that could be passed down, including routes to the best berry patches and where and how fish could be caught and animals hunted. The people were one with the land, not just on it.

This all changed in the 1800s due to colonization.

A man by the name of Samuel Hancock was looking for coal when he met the sdukʷalbixʷ (Snoqualmie) tribe. He hired tribal members to bring him upriver to survey the area, posing as a merchant who could be an ally to the community. In reality, Hancock was searching for coal deposits. His guides told him the area was called “a good (or productive)” land. To Hancock this meant the land was valuable for mining and timber potential.

While the land wasn’t officially taken until ratification of the Point Elliott Treaty in 1859, colonists immediately began using the native lands. This and other treaties signed at the same time established the Washington Territory. Without repercussion, the U.S. sold native lands. With their land rights taken, much of the tribe was forced to the state’s allotted “native” land plats, 50-plus miles from the land their ancestors had stewarded since time immemorial. With the move they lost access to their traditional travel routes and to their harvesting areas for first foods.

With steamboat travel active on the Skykomish River by the 1870s and the nearby railway completed in 1893, the population grew rapidly, and with the growth came new plants being introduced and land disturbances — likely knotweed among them. The largest influx of settlers came with the highway system. Highway 2, the main road that parallels the Skykomish River, opened in the 1920s, following the routes of Indian trails. As travel became easier, the local economy shifted to mining and logging. Logging quite likely contributed to knotweed’s spread. By dragging heavy machinery and dropping multi-ton trees onto the surface, it is clear how the hollow knotweed stems could dissemble, turning one plant into 10 in a matter of seconds.

While it’s unclear what year knotweed first grew in this valley, it is presumed it was in the early 1900s. It was marketed as an ornamental shrub known to do well in wet areas. This is what eventually led to the Skykomish Valley infestation. Locals suggest the first notable knotweed planting occurred only a few miles upstream.

Flowering knotweed. photo by Sara Price, KCNWCP

knotweed’s invasion success

One desirable aspect of knotweed as an ornamental is exactly what makes it so hard to manage: its ability to reproduce from plant fragments and seeds. Knotweed seeds are good at their job. They have high germination rates — nine out of ten seeds that reach moist soil are likely to form new plants. The small seeds often take ground near their parent plant but can travel via wind and water. Buoyant seeds can float long distances. Tiny seeds stick easily onto shoes and machinery, introducing new plants wherever they find suitable conditions.

Knotweed also reproduces via fragments. Knotweed’s former genus, Polygonum¸ was named after the plants plentiful (Poly-) nodes (or “knees,” -gonum). In contact with moist soil, each node can produce a new plant. Plants can regenerate from just one centimeter of the plant’s robust root system. All these things make the plant hard to eradicate, as cutting and digging the plant often make the problem worse.

the problem

Knotweed disturbs ecosystems in several ways. In the summer, plants may reach 20 feet tall or taller, shading out everything below. This crowds out native plants and discourages any new plants from coming up. In the winter the plants die back to ground level, and animals that historically relied on native plants are left without a habitat. Knotweed forms “monocultures,” large stands of plants with no other plants in sight. These stands create barriers for humans and animals of all sizes. Many native plants rely on nitrogen from leaf litter as a vital nutrient. Native plants have been shown to re-absorb small amounts of the nitrogen they give up through litterfall and death, rates of 2-33% have been reported in the literature, whereas knotweed has been shown in studies to reabsorb more than 75% of its own nitrogen prior to litterfall, depriving the surrounding soil and other plants of nutrients.

restoration and reparation: a stewardship response to the knotweed invasion

Many consider the 1970s the start of the modern environmental movement, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that legislation was in place to protect Pacific Northwest forests. The Northwest Forest Plan of 1992 established new guidelines for the forestry industry. In 1998 the logging company that had purchased millions of acres of land in the valley from the government sold its lot to the U.S. Department of Agriculture as forest land. It was around this time that the present-day King County Noxious Weed Control Program got its start.

Knotweed was not a regulated plant when the program started, and King County’s noxious weed program consisted of one full-time coordinator and six temporary weed inspectors who focused on the control of regulated weeds. The program’s capacity was limited and by 1997 it was clear that the amount of knotweed exceeded the program’s ability to control it. However, the County saw the negative impacts of knotweed on the environment and knew it needed to be controlled. The team needed to convince grantors of the weed’s impact, and thankfully, knotweed’s multiple impacts on native ecosystems made this easy.

By 2004, knotweed-specific projects were funded and underway. Work at the Skykomish site, known informally as “Skylandia,” started in 2014. The area had fundamentally changed from a 100% native understory with foot paths and cultural burning to control vegetation, to a rural neighborhood off the paved highway with homes, dirt roads, and bridges to cross the many natural creeks that were no longer allowed to flow freely. The team now had four, full-time staff dedicated to knotweed control along riparian areas and one specialist specifically assigned to weed management along the Skykomish River.

Knotweed control is different from control of other weed species because digging is almost never an option. Also, it has a narrow time window in summer where control is effective. With the exception of new growth (NOT regrowth), if you were to attempt to dig out a knotweed plant you would be assisting it in its spread. Every time you break the ground and disturb roots, new plants are encouraged to grow from these new fragments. Covering the plants with a loose, thick fabric can be effective in small patches, but it can be very cumbersome and difficult to deploy across large areas. This is why King County uses herbicides for knotweed. Our program specialists have special licenses and training to perform these treatments and do so with great care. For smaller patches the team has used “injectors” to inject concentrated chemical into each stem, but this is labor-intensive and uses a greater amount of chemicals. More often foliar sprays are used because they are quicker to apply and use lower concentrations, so they put less herbicide into the environment. Because of the limited window for application and the large amount of knotweed, each site typically gets visited once and sometimes twice per season. Therefore, the team must return to sites for several years to deplete the plants extremely large root systems.

King County started controlling knotweed in 2015. Each year the knotweed population shrank, until in 2018, the third year of treatment, a seasoned specialist came across a well-hidden knotweed infestation: 2.4 acres, nearly two football fields worth of knotweed towering 15-20 feet high, that had likely been growing for decades. A mature monoculture like the infestation found in 2018 is treated by spraying using a low concentration (< 2%) of the herbicide imazapyr from beneath the canopy on the underside of the leaves and stems without having to worry about damaging native plants, as they were all replaced by the knotweed. Imazapyr will harm native plants if they are present, but the EPA classifies imazapyr as “practically non-toxic” to wildlife species in the area. This is the conflicting benefit of treating monocultures: while it would be better if native plants could thrive, it’s a relief knowing that unintended harm is minimized. As mentioned earlier, knotweed is nearly impossible to control in these amounts and it is vital that we manage large patches like this before they have the chance to overtake more of this natural wetland area.

It has been four years since the initial management effort, and the treatment time has been cut in half and shrinks every year. Knotweed is an incredibly hardy species — its goal is survival, and it does that well. Because its ability to reproduce from broken fragments and roots, the site from 2018 will not be replanted with native vegetation until the danger of knotweed regrowth is substantially decreased, which is determined by monitoring to confirm that the monoculture is gone and regrowth is minimal.

Less-densely infested areas of the site treated since 2015 opened space for native plantings that took place in 2020 alongside Forterra, a land conservation organization partnering in these efforts.

Treatment will continue for many years to come. While it is impossible to go back in time and restore the site to its pre-colonization state, restoration is one attempt at reparations in the Puget Sound region.

FIND OUT MORE

For more information and resources on knotweed control, visit King County’s knotweed website.

History of Knotweed (Fallopia spp.) Invasiveness by Drazan et al. 2021

Learn more about the ecological and human history of the Snoqualmie-Skykomish Watershed.

Educate yourself about the historic and ongoing struggles that our native communities face and take action: Ecotrust Indigenous Leadership Briefings: Ensuring Native Futures.

For more source information please contact the author at: spelliccia@kingcounty.gov

Skye Pelliccia (she/her) is a noxious weed control specialist and educator for the King County Noxious Weed Control Program in Seattle. She is a member of the Tuscarora Nation Southern Band, a federally unrecognized tribe that shares the name and ancestral lineage with the federally recognized Tuscarora Nation Northern Tribes. Her other ancestors descend from the Diné (Navajo People) and Thailand. Skye has a degree in environmental geology and has studied native law and water and land rights. Skye’s work on noxious weed management is an effort to protect native plants and first foods and to use environmental education as a tool to create space for native voices and recognition.

Table of Contents, Issue #16, Summer 2022

CWMA photos

by Douglas Crist — Issue 16, Summer 2022Friends of the Farms partnering with Island School to clear invasive species and establish native, primarily edible plants at the Bainbridge Island Native Food Forest. An educational ecosystem restoration project, building...

Double Jeopardy

The Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022Purple varnish clam. photo by John F. WilliamsThe Intersection of Climate Change and Invasive Species By Paul Heimowitz, Summer 2022The arrival of non-indigenous people to the Salish...

Green Frog

Female green frog at county stormwater pond #147. photo by Elizabeth Springborn Melissa Fleming, Ph.D.Photos by Melissa Fleming except as notedSummer 2022The green frog (Lithobates [Rana] clamitans) is the classic frog of my East Coast childhood: often the size of...

Garden Escapees

by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah)English ivy (Hedera helix) creeps through the fence and overwhelms an intentionally planted native orange honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa).by Sarah Lorse (photos also by Sarah) Issue 16, Summer 2022It is easy for us gardeners to pick...

Invasives and killer whales

Orca mother and child. photo courtesy of NOAATara Galuska, Governor’s Salmon Recovery OfficeChelsea Krimme and Justin Bush, Washington Invasive Species Council Summer 2022The image of a large, black-and-white killer whale jumping from the water before falling back...

Poetry-16

Summer 2022Western redcedar. photo by John F. WilliamsSummer 2022INVASION by Diane Moser Beneath my windowcedars as old as Lewis and Clarkeclimb skywardreaching for rain and morning light. They try to ignore the ivythat climbs their trunk,invasive tentacles...

European Green Crab

the key to management success is community collaboration By Leah Robison (Northwest Straits Commission) and Chase Gunnell (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Summer 2022Large European green crab. photo by by Jonathon Hallenbeckthe key to management success...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.