RESTORING FORESTS TO IMPROVE SALMON LIFE CYCLES WITHIN THE MOUNTAINS TO SOUND GREENWAY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

by Dan Hintz, Winter 2020

You can see this 2019 Mountains to Sound Greenway tree planting site at Lake Sammamish State Park, located along Issaquah Creek. Photo by Katie Egresi.

You can see this 2019 Mountains to Sound Greenway tree planting site at Lake Sammamish State Park, located along Issaquah Creek. Photo by Katie Egresi.

RESTORING FORESTS TO IMPROVE SALMON LIFE CYCLES WITHIN THE MOUNTAINS TO SOUND GREENWAY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

by Dan Hintz, Winter 2020

Salmon from Sunset Way Bridge in downtown Issaquah in early October. Photo by Dan Hintz.

This fall marked the fifty-first anniversary of the Issaquah Salmon Days Festival, a community-organized festival held annually during the first weekend of October. While there was no parade, live music, arts, crafts, or food vendors this year due to the ongoing pandemic, one cycle remained unbroken: the festival honorees (our native salmon) still returned to Issaquah Creek to spawn in their birth-waters.

This annual migration of salmon returning from the ocean to their natal streams to spawn their next generation (and then die) usually peaks in early October, but salmon can be seen in the rivers of western Washington from August into December. Walk across any of the bridges in downtown Issaquah during this time period (the bridge over Issaquah Creek on Sunset Way is a particularly good spot), and you are likely to see salmon splashing, chasing each other around, and most importantly, looking for the perfect gravelly spot to deposit their eggs.

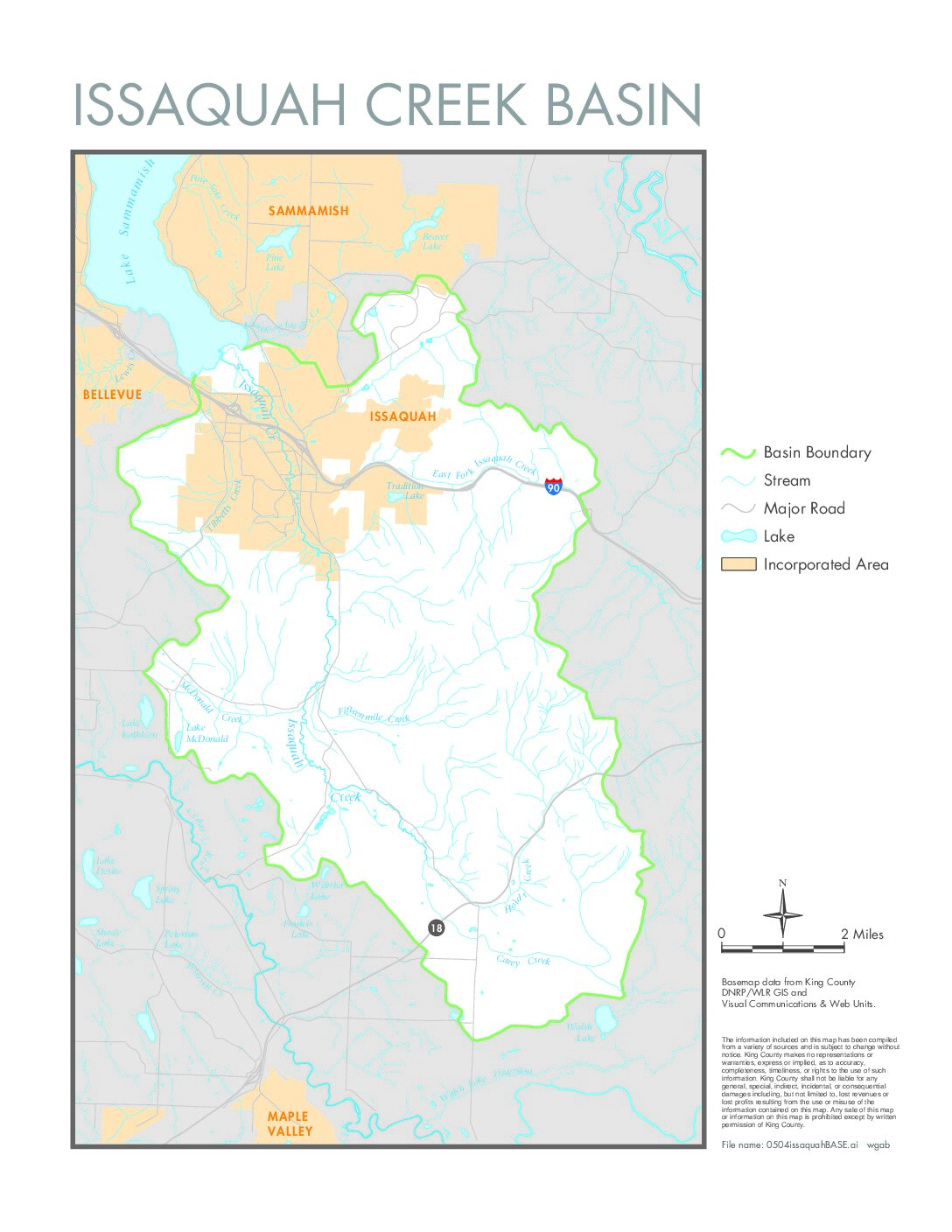

Issaquah Creek, which flows between Tiger and Squak Mountains in the Issaquah Alps before emptying out into Lake Sammamish, is critical habitat for our native Chinook salmon, a federally listed “threatened” species under the Endangered Species Act. Like many of our aquatic ecosystems that connect to the Salish Sea, Issaquah Creek has been ecologically degraded since Europeans began settling the Issaquah area in the late 1800s. From cattle ranching and dairy barns, coal mining, logging, and more recently urban development, habitat for salmon has been negatively impacted by human actions for over a century.

While these human activities have been essential to the growth of the Salish Sea region, we have a lot of catching up to do to ensure a healthy balance between people and salmon. The Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust has been working for over two decades to restore habitat along Issaquah Creek.

Restoration work has occurred along sections of all 13 miles of Issaquah Creek, partnering with local agencies like the City of Issaquah, King County, the Department of Natural Resources, and private landowners to implement projects. However, one location stands out for the scale and visibility of salmon habitat restoration work: Lake Sammamish State Park.

This is an aerial photo of Issaquah Creek within Lake Sammamish State Park. All the smaller trees were planted by the Greenway Trust. Photo courtesy of the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust.

Chinook salmon population numbers have been declining over the past several decades, and the reasons are complex. When talking about Salmon Recovery, you often hear of the four “H’s”: Hatcheries, Hydropower, Harvest, and Habitat. The restoration at Lake Sammamish State Park focuses on the latter “H,” habitat. Salmon need freshwater streams like Issaquah Creek to spawn, and for juvenile salmon to feed, grow, and hide from predators in freshwater before making their journey through the Salish Sea and out to the Pacific Ocean.

Major indicators for healthy freshwater salmon habitat are stream temperature (salmon need cool water), water quality (pollution and other runoff can endanger salmon), dissolved oxygen levels (salmon need healthy oxygen levels for aquatic life), food sources (presence of macroinvertebrates for example), and instream habitat diversity such as deep water pools, flood refuge, edge habitat, and more generally, places to hide.

Issaquah Creek Confluence Park.

The red circle outlines “natural recruitment of large woody material.” This is a fancy way of saying wood (branches or whole trees) that fell naturally into the stream (due to wind, flooding, beavers etc.). The western red cedar highlighted in red was planted by the Greenway Trust about 15 years ago and now provides cover and refuge for juvenile salmon. Vegetation and wood interacting with water also attract macroinvertebrates which are important food sources for our native fish!

The blue area highlights more natural recruitment of large woody material (large cottonwood tree) and the grey area shows the gravel bar forming behind the woody material. The wood slows down the water during floods and that allows for larger gravel material to “drop out” and aggregate. This larger gravel material is essential as a spawning substrate for our Chinook salmon.

Photo by Dan Hintz.

Arguably, no other living things connect more directly to these critical elements of freshwater salmon habitat restoration than trees! Trees provide shade for our rivers, filter pollutants from stormwater runoff, attract insects and other food sources for fish, and even after they die, fall into our streams and increase the instream habitat complexity which is so essential for salmon.

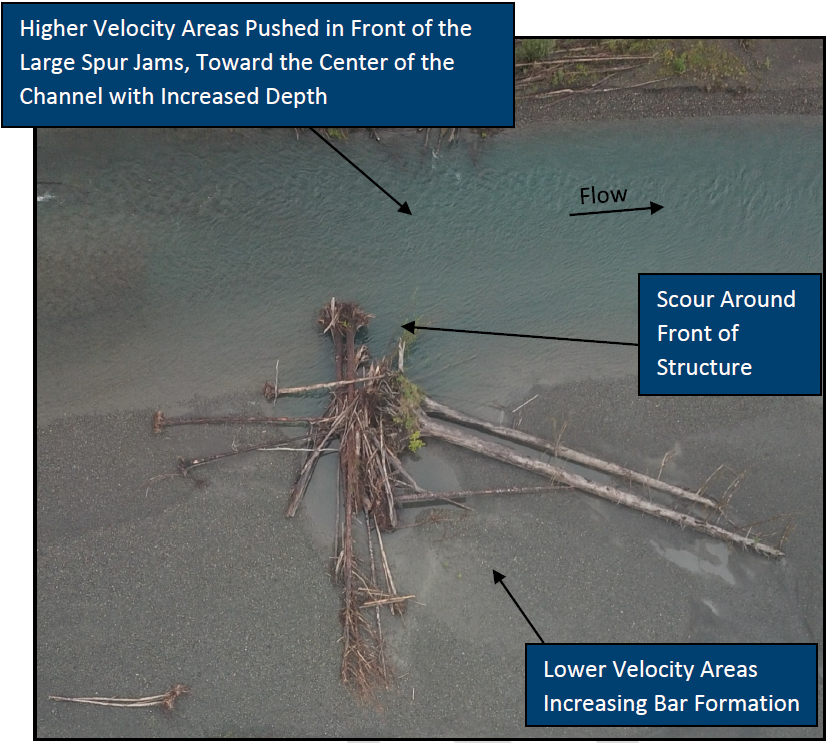

This graphic from Northwest Hydraulic Consultants shows how spur jams form instream complexity. Look closely inside circle to see young salmon enjoying the complexity.

This brings us back to Lake Sammamish State Park, where the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust staff and AmeriCorps members, and a total of 64,000 volunteer hours have contributed to planting over 50,000 native trees and shrubs across 60 acres of Issaquah Creek’s riparian buffer since 2002. This project work was primarily funded by the WRIA 8 Cooperative Watershed Management Grant Program.

2019 Tree Planting Celebration at Lake Sammamish State Park, right along Issaquah Creek. Photo by Katie Egresi.

Walk any of the trails (Sunset Beach is a good place to start) along the mile-plus of Issaquah Creek that passes through the State Park, and you can see young forests developing along with a few old relic cottonwood trees (which the bald eagles and blue herons love) that survived the tree clearing and wetland draining for the dairy farms that occupied this land before it became a State Park.

Although planting a tree into the floodplain soils along Issaquah Creek is, in and of itself, a fairly simple task, ensuring that those seedlings grow into tall, mature trees that enhance salmon habitat is an effort full of seasonal cycles, repetition, and much sweat and blood, often produced by removing the thorny, invasive blackberries that do their absolute best to persist and outcompete our native trees. Most native trees can provide some ecological lift and function for streamside habitats, but it is our native evergreen conifer trees, like Western red cedar, Douglas fir, and Sitka spruce, which are the stalwarts of riparian (streamside) restoration.

For these recently planted conifers, you could be talking about hundreds of years from tree planting to mature trees dying and falling into Issaquah Creek to improve instream habitat. Restoration is not a pursuit for those who lack patience. For every annual tree growth ring created, there are many factors and forces that our native conifers must face to survive. After planting trees during our reliably rainy fall and winter months, young trees with limited root systems must quickly adapt to native soils (often depleted of nutrients due to past agriculture use and lack of organic inputs like leaves and branches), summer heat and droughts, insect pests and deer herbivory, and of course the persistent invasive plant species that are not ready to give up their dominance so easily.

This is a large spur jam on Issaquah Creek within Lake Sammamish State Park. The spur jam causes scouring around the front of jam and increases stream sinuosity. Streams naturally meander, but a long history of human impacts often cause streams (especially in urban areas) to become fast flowing straight channels that provide little instream habitat and complexity. More sinuosity provides more complexity, broader flood plains, more refuge habitat for salmon, and will increase natural recruitment of large wood material.

Photo courtesy of Northwest Hydraulic Consultants.

These annual battles are most important during what we call the tree (or stand) establishment phase, which usually takes at least 5–10 years after tree planting. Volunteers and seasonal crews have spent thousands of hours at Lake Sammamish State Park removing invasive weeds to decrease competition, spreading mulch to improve soil conditions, watering trees, installing plant protection to keep deer from girdling trees, and inevitably, replanting trees to replace ones that don’t make it through those early, vulnerable years.

A restoration program calendar for this type of work is so consistent year to year it can seem like déjà vu all over again. However, after the excitement of planting your first trees at a restoration site, it is really the next several annual cycles of maintenance that ensure a successful project and healthy long-term trajectory for our burgeoning forests. Unfortunately, this maintenance is often hard to fund as grants have limited timelines, and there can be fundraising fatigue over raising money for the same project areas year after year. It is critical that we keep an eye on the big picture and realize that a century-plus of habitat degradation and declining salmon populations will not be fixed overnight. It takes consistent dedication, hard work, and repetitive maintenance activities, like pulling the same weeds every spring and adding more mulch to a site you mulched two years ago.

An example of how spur jams form instream complexity. Photo courtesy of Northwest Hydraulic Consultants.

There are ways to jumpstart the instream restoration processes. For instance, the Greenway Trust and the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission are designing a project to install large woody material (LWM) directly into Issaquah Creek within the State Park to achieve conditions more closely resembling the instream wood levels and complexity prior to disturbance. This approach can be seen already along other stretches of Issaquah Creek like at Confluence Park and Salmon Run Nature Park.

The cumulative impacts of these approaches and projects over the course of decades is already showing positive results for forest recovery and cautious optimism around salmon returning to Issaquah Creek. As mentioned before, there are other areas besides freshwater habitat restoration that impact salmon recovery. However, Issaquah Creek, and many other salmon-bearing streams connected to the Salish Sea have seen dramatic increases in riparian forest cover, reductions of invasive species like knotweed, and inputs of large wood material over the past several decades.

In the red circle is a root wad in Lake Sammamish State Park that likely washed up during the February 2020 floods. The root wad slows down stream velocity, causing gravel (important substrate for Chinook spawning) to aggregate behind the wood (grey area). Upstream of the root wad fast moving water diverts around the woody material and causes scouring (blue area) and two channels that flow on both sides of the gravel bar. The scouring process is important since it forms pools, which are vital for providing cold water habitat (warm stream temperatures in the spring and summer can be deadly for both adult and juvenile salmon) and also areas for refuge and feeding. In this stretch, Issaquah Creek goes from about six inches to almost six feet deep in the pool in front of the root wad! Photo by Katie Egresi.

While there is certainly still an urgency to fund and implement more of this work, there is also a pleasure and satisfaction that comes with the cyclical restoration of nature. Restoration work needs to be appreciated for these incremental, relentless gains that come from putting a tree in the ground, watching it leaf out in the spring, clearing it of invasive weeds in the summer, and remembering that if we do this right, those trees will provide for salmon long after our time passes on this earth.

As Restoration Projects Manager for Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust, Dan is responsible for developing and implementing restoration projects throughout the Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area. These projects focus primarily on riparian and instream habitat restoration, following regional salmon recovery goals and initiatives. Dan also supervises the Greenway’s seasonal restoration crew, who implement the bulk of the Greenway’s ecological restoration work.

Dan grew up outside of Chicago and attended the University of Wisconsin where he studied economics and environmental sciences before moving to Seattle to serve as an AmeriCorps member with EarthCorps. Since then, Dan has lived in Washington and worked restoration jobs for local government, non-profits, and a private contractor. Dan finished his Master of Environmental Horticulture degree at the University of Washington just after joining the Greenway Trust in the spring of 2016. In his spare time, Dan enjoys hiking, searching for old growth trees, playing guitar, and watching Cubs baseball.

FIND OUT MORE

The Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area is a unique geographic corridor made up of connected ecosystems and communities spanning 1.5-million acres from Seattle to Ellensburg. National Heritage Areas are defined as places where historic, cultural, and natural resources combine to form cohesive, nationally important landscapes. The Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust is a coalition-based organization that leads and inspires action to conserve and enhance this special landscape, ensuring a long-term balance between people and nature.

We work to conserve and restore natural lands, open spaces, and historic sites; build and maintain recreational trails; engage with students through our environmental education program; advocate for public lands and recreational access; lead a robust volunteer program; and so much more.

Table of Contents, Issue #10, Winter 2020

Woodland Witness

by Zoe Wadkins Winter 2020 Drawings by Zoe Wadkinsby Zoe Wadkins, Winter 2020 Drawings by Zoe WadkinsIn the three years since our first introduction, I have walked this loop of Deer Creek more than one hundred times. Its rich macroinvertebrate habitat constitutes a...

Salish Sea and Dinosaur Pee

by Sarah Lorse, Winter 2020 Photo by Sarah Lorseby Sarah Lorse, Winter 2020 Photo by Sarah LorseHow wonderfully wet things are here beside the Salish sea. Whether it is a big fat raindrop dangling off your nose or the impressive volume of a king tide, water is all...

See the Salish Sea by Saddle

by Jessica C. Levine, Winter 2020 Photos by Jessica C. Levineby Jessica C. Levine, Winter 2020 Photos by Jessica C. LevineI spend a considerable amount of time pondering cycles. As a cyclist, I bike year round. I’m also a naturalist and place-based science educator....

Many Cycles of Nature

by Leigh Calvez, Winter 2020 Photos by John F. Williams except as notedby Leigh Calvez, Winter 2020 Photos by John F. Williams except as notedAs children we come into a world filled with the cycles of nature. We watch with wonder as the first crocuses of spring poke...

Swallow Season

by Donna Bunten, Winter 2020 Photos by Donna Bunten except as notedPhoto by John F. WilliamsPhoto by John F. Williamsby Donna Bunten, Winter 2020 Photos by Donna Bunten except as notedI dread August—the end of summer, sliding farther down the slope towards darkness,...

Sacred Stream Insects

by Gavin Tiemeyer, Winter 2020 Photos courtesy of King County except where notedby Gavin Tiemeyer, Winter 2020 Photos courtesy of King County except where notedLearning about the natural cycles that govern the health of the Salish Sea starts with peering into your...

Issue 10 Poetry

Winter 2020Photo by Adelia RitchiePhoto by Adelia RitchieWinter 2020Water Drop By Mahathi Mangipudi Wide strokes of grey paint the sky On the windward side of the Cascades Air masses from the Pacific Ocean Saturated with water vapor Condense into little...

The Many Lives of Tree

by Pat Kirschbaum, Winter 2020Photo by John F. WilliamsPhoto by John F. Williamsby Pat Kirschbaum, Winter 2020We are so lucky in the Pacific Northwest to have many places to go where we can be surrounded by trees. As I sat alongside a nearby stream recently, I...

Community Gardens

by Alison Ahlgrim, Winter 2020Photo by Michael YatesPhoto by Michael Yatesby Alison Ahlgrim, Winter 2020My first visit to Everett was a reconnaissance mission to see if my husband and I might like to live there. Drawn to the water, we ended up at the waterfront...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.