BLUE CARBON AND WETLANDS

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020

Underwater Rainbow, painting by Julia Miller

Underwater Rainbow, painting by Julia Miller

BLUE CARBON AND WETLANDS

by Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020

As you’ll see everywhere else in this issue, a wetland system isn’t just another lovely place for a nature walk. Wetland ecosystems protect us from storms and floods, they provide vital nursery grounds for fish and other marine life, and they are among the most productive ecosystems in the world, comparable to rain forests and coral reefs. An immense variety of species of microbes, plants, insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, fish, and mammals compose our local wetland ecosystems. And wetlands can even reveal the history of earthquakes and tsunamis in their sediments.

We also know that wetlands provide another vital service — sequestering and storing carbon from the atmosphere — and therefore are an essential piece of the solution to global climate change.

See the Table of Contents below for other articles in this issue that address these topics.

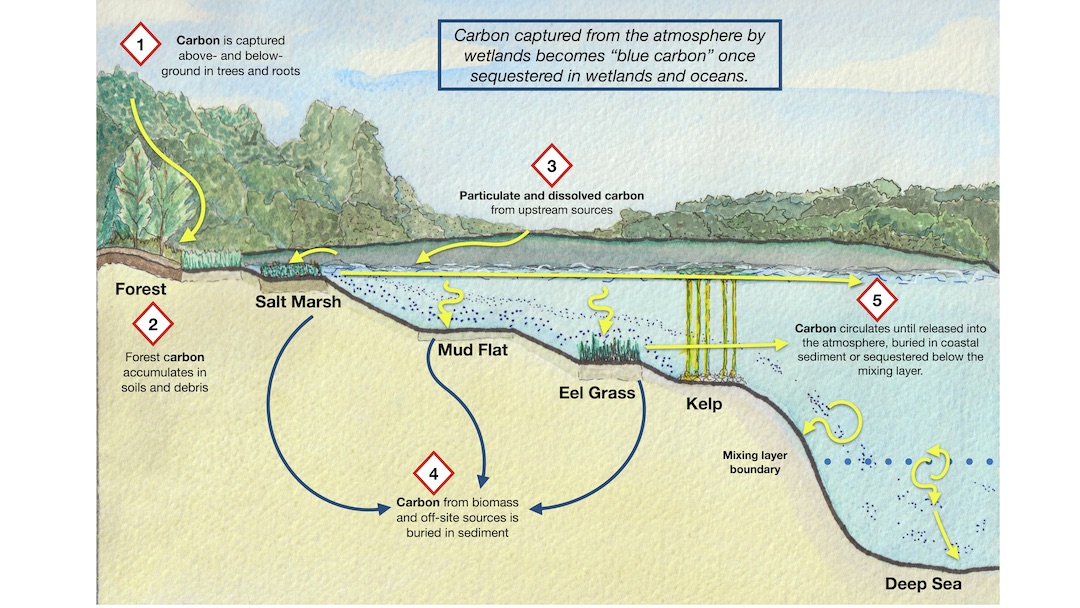

“Blue carbon” is simply a term for carbon dioxide that is captured from the atmosphere by the world’s ocean and coastal ecosystems and stored in the form of biomass and sediments. We now know that human activities give off carbon dioxide, which is a greenhouse gas once it enters the atmosphere. The good news is that our oceans and coastal wetlands provide a natural way of reducing the impact of these gases on our climate through sequestration (or capturing) of this carbon.

Sea grasses, mud flats, kelp, and tidal marshes along our coast capture and hold carbon, acting as a carbon sink. These coastal systems, though much smaller in size, sequester this carbon at a much faster rate than rain forests, and can continue to do so for millions of years. Most of the carbon taken up by these ecosystems is stored below ground where we can’t see it, but it is still there locked safely away.

What is a “greenhouse gas”? When in our atmosphere, a so-called “greenhouse” gas –– carbon dioxide, methane (natural gas), nitrous oxide or ozone –– acts just like the glass walls of a land-based greenhouse. It lets light and heat in, but it traps and holds the heat. Without any greenhouse gases, it would be freezing on our planet! With just the right amount of greenhouse gases, we are in the “Goldilocks zone” where life has evolved for millions of years. However, when too much carbon dioxide is allowed to escape into the atmosphere, the planet warms, ice caps melt, plant and animal life begins to suffer, and eventually, if left unchecked, life on Earth would be in very big trouble.

Let’s talk about the basics of carbon capture.

Referring to the illustration above, the entire process begins in upland forests and other upstream sources. The plants grab carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, and carbon in the water upstream flows downstream.

Referring to the illustration above, the entire process begins in upland forests and other upstream sources. The plants grab carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, and carbon in the water upstream flows downstream.

All those dead leaves, needles, and branches that you walk on or step over on your forest walks are in the process of becoming deep ocean sediments! As trees, shrubs, and animals die, the carbon compounds in their leaves, limbs, and bodies decompose and return to the earth where the rains wash them downhill to rivers and streams, stopping in wetlands along the way.

All those dead leaves, needles, and branches that you walk on or step over on your forest walks are in the process of becoming deep ocean sediments! As trees, shrubs, and animals die, the carbon compounds in their leaves, limbs, and bodies decompose and return to the earth where the rains wash them downhill to rivers and streams, stopping in wetlands along the way.

Eventually, this “recycled” carbon reaches marshes and estuaries, becoming food for other creatures. Over time, this carbon-containing biomass reaches the deep blue sea, where it is held safely away for a very long time.

Eventually, this “recycled” carbon reaches marshes and estuaries, becoming food for other creatures. Over time, this carbon-containing biomass reaches the deep blue sea, where it is held safely away for a very long time.

Consider for a moment how this would be different if the trees in the upland forest had burned instead of living out their natural lives. Instead of being used and reused and ultimately stored safely away at the bottom of the sea, the carbon in those trees would have gone directly into the atmosphere, adding to the greenhouse effect and continuing to overheat our planet!

So, how exactly do healthy coastal wetlands mitigate climate change? That was the question that sparked John Rybczyk’s research at Western Washington University. This video, filmed in the Snohomish Estuary in Puget Sound and presented by EarthCorps and Restore America’s Estuaries, is one of the best examples I’ve seen about the important work being done in our region to restore all the functions of a wetland, including carbon sequestration.

Credits: Video features in order of appearance: Terry Williams, Tulalip Tribe; John Rybczyk, Western Washington University; Stefanie Simpson, Restore America’s Estuaries; Katrina Poppe, Western Washington University; Mariska Kecskes, EarthCorps; Mike Rustay, Snohomish County.

After watching this video and reading all the great articles in the rest of this issue, I hope that the next time you hear the phrase, “Drain the swamp!”, your immediate response will be, “No! We must never do that again!”

Adelia Ritchie grew up on a northern Virginia farm with horses, cattle, dogs, and her pet pig Porky, who ran the whole show. A long-time resident of the great Pacific Northwest, Adelia is a serial entrepreneur, scientist, educator, and artist, and currently works with educators and legislators to promote a deeper understanding of the science of climate change and its impacts on the complex ecological web of life. Adelia resides in Hansville, WA, with her garden, her dogs, and a flock of very entertaining chickens.

Julia Miller (Julia V. Miller Fine Art) likes nothing better than exploring a quiet forest or scrambling over a rocky beach. Her artwork expresses the delight she finds in the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest. Born and raised in the Seattle area, a University of Washington graduate, the Kitsap peninsula is now the home of her dreams.

Julia began painting after leaving a long stint as a popular natural foods restaurateur. She describes her painting style as “unhampered by formal training” and her work has been called “color poetry.”

Table of Contents, Issue #9, Autumn 2020

From Swamps and Bogs …

by Sara & Thomas Noland, Autumn 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedby Sara & Thomas Noland, Summer 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedWetlands are part of our landscape here in the lowlands near the Salish Sea. Anyone who’s walked around in a...

Issue 9 Art Poetry

Autumn 2020Juan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaJuan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaSummer 2020Going Home, painting by Julia MillerComing Home by Dawn Henthorn Salmon come home home to the Elwha. Bit by bit of rubble two feet at a time, the dams were removed,...

Salt Marshes

by Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020Gumweed photo by John F. WilliamsGumweed photo by John F. Williamsby Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020I’ve enjoyed, studied, mapped, and tried to protect wet places for pretty much my entire life. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share some...

Importance of Wetlands

by Josh Wozniak, Autumn 2020 Photographs by John F. Williamsby Josh Wozniak, Summer 2020 Photographs by John F. WilliamsTaking many forms, wetlands are natural features of the landscape that provide crucial functions for both nature and humankind. We benefit directly...

Newts: Wetland Magicians

by Sharon & Paul Pegany, Autumn 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany except as notedby Sharon & Paul Pegany, Summer 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany, except as noted. Did I just see what I think I saw? I had to do a double take while exploring the edge of a local pond...

Healthy Wetlands

by Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Autumn 2020Wetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. WilliamsWetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. Williamsby Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Summer 2020For the 4.2 million residents in and around Puget Sound, there is a good...

Earthquakes and Tsunamis

by Carrie Garrison-Laney and Ian Miller Autumn 2020 A photo of sediments in the coastal marsh near the mouth of Salt Creek on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, showing distinct bands of different colors and textures. Photo by Ian Miller.A photo of sediments in the coastal...

10 Things About Duckweed

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as notedby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as noted1. Duckweed grows in dense colonies in quiet water that is undisturbed by wave action. We try to avoid insulting still...

Carpenter Creek Salt Marsh

by Melissa Fleming & Terry Pereida, Autumn 2020 Photos by Terry Pereida, except as notedSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom TwiggSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom Twiggby Melissa Fleming &...

Wetland Basics

Frank Stricklin, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams except as notedThis large wetland in Newberry Hill Heritage Park is listed by the State of Washington as a “wetland of significant conservation value.” It contains many species of aquatic plants, and some...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

FIND OUT MORE

Hart, Curt and Marcus Humberg. Healthy Wetlands Mean a Healthy Salish Sea, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020

Miller, Ian and Carrie Garrison-Laney. Records of Earthquakes and Tsunamis Found in Salish Sea Coastal Wetlands, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020

Noland, Sara and Thomas Noland. From Swamps and Bogs to Marshes and Meadows, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020

Pegany, Sharon and Paul Pegany. Newts: Wetland Magicians, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020

Stricklin, Frank. Wetland Basics, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020

Wozniak, Josh. The Importance of Wetlands, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020

Fleming, Melissa and Terry Pereida. Carpenter Creek Salt Marsh, Salish Magazine, Autumn 2020