A HEALTHY SALISH SEA REQUIRES HEALTHY WETLANDS

by Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Autumn 2020

Wetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. Williams

Wetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. Williams

A HEALTHY SALISH SEA REQUIRES HEALTHY WETLANDS

by Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Summer 2020

For the 4.2 million residents in and around Puget Sound, there is a good chance they live, work, or play near a wetland.

According to a 1990 report to Congress, Washington’s wetlands — places where water is present at or near the surface of the soil at least part of the year — cover 938,000 acres, or nearly 1,500 square miles, around 2% of Washington state’s total land area.

While flooded forests, soggy meadows, and salt marshes may not seem important, they represent some of the state’s most environmentally important and economically valuable natural resources. They guard the health of the Salish Sea and help keep watersheds, communities, and wildlife healthy and safe.

Unfortunately, wetlands are highly endangered ecosystems. Since European settlers arrived in 1790, more than half of Washington’s original wetlands have been drained, dredged, or filled. In some Puget Sound estuaries, over 90% of the original saltwater wetlands have been lost to urban growth and development.

why do we care about wetlands?

Each wetland is a unique and valuable resource. Some ebb and flow with the seasons, transitioning from sodden, impassible fields replete with sedges, rushes and grasses, to dry summer meadows, reappearing only when the rains return. Other wetlands — slow-moving pools, ponds, and lakesides bounded by willows, cattails, and reeds — seem almost permanent and unchanging in the landscape.

See the article From Swamps & Bogs to Marshes & Meadows for more about the different kinds of wetlands.

See the article From Swamps & Bogs to Marshes & Meadows for more about the different kinds of wetlands.

These soggy spaces flourish with life. Water striders and whirligig beetles glide over the surface with waterfowl. Herons, eagles, and osprey hunt among their bounty. Salmon fry swim, hide, and feed before their journey to the sea. Otters cavort, and beavers enhance, and even engineer, wetlands. Swifts, swallows, and bats flit erratically, feeding on plentiful insects. Tadpoles transition to frogs, toads, and salamanders before the dry season.

Coastal wetlands in Puget Sound serve as a vital bridge between fresh and marine water environments. They are also among the most complex ecosystems on earth, rivaling tropical rain forests and coral reefs for the diversity of life and natural systems they support. They are popular places for people seeking to spend time in nature while hiking, birdwatching, boating, and fishing.

Saltwater wetlands are Salish Sea nurseries. Clams, crabs, shrimp, and other marine life often start their lives in fertile estuarine deltas, shallow tide flats, and eelgrass beds. These wetlands provide refuge for migrating shorebirds and waterfowl as well as forage fish, such as perch and herring. Without these wetlands, the salmon that Puget Sound’s endangered southern resident orca depend on could be lost.

In addition to providing habitat, wetlands help curb climate change by capturing and sequestering carbon and serving as a buffer against rising seas. They absorb floodwaters, runoff, and energy from storms. They control erosion by serving as transition zones between dry land and waterways. Wetlands help filter sediments and pollutants from surface water while helping recharge underground water supplies, including drinking water aquifers.

See the Blue Carbon article in this issue for more about wetlands sequestering carbon.

See the Blue Carbon article in this issue for more about wetlands sequestering carbon.

Discovery Bay, Coastal Atlas Photo, WA Department of Ecology

If communities had to artificially engineer all the benefits wetlands provide, the cost to Puget Sound’s economy could easily top $10 billion. It is more cost effective to protect wetlands than attempt to replace them.

how are we protecting washington wetlands?

As recently as 1990, Washington was losing on average 2,000 wetland acres annually — including 900 acres of freshwater wetlands a year in urban areas, especially around Puget Sound. This trend has been reversing since 1989 when Gov. Booth Gardner enacted an executive order, still in effect, requiring a no-net-loss in the acreage and function of remaining state wetlands.

Under this mandate, The Washington State Department of Ecology (WSDOE), other state agencies, and local governments are working to protect wetlands. This includes helping local partners develop land-use policies and regulations that protect wetland resources.

how is development affected?

WSDOE provides technical assistance to local governments and other parties, and it reviews development proposals to ensure potential wetland impacts are considered. The agency develops mitigation policies to offset unavoidable impacts to wetlands, and it helps organizations obtain wetland conservation funding.

When public and private developers seek to construct projects with potential wetland impacts, state law requires developers to avoid impacts first. If impacts are unavoidable, developers must minimize harm, move and replace affected wetlands, reduce or eliminate impacts over time, and protect and monitor the site. These requirements become part of the conditions for projects to continue.

To protect coastal wetlands, WSDOE works in partnership with nonprofits and local and tribal governments to help secure National Coastal Wetland Conservation grants. These grants, offered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have successfully funded $122 million in projects to conserve 13,000 acres of coastal wetlands, mostly in Puget Sound.

an example

In Puget Sound, the Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve located along the Skagit River delta is a “shoreline of statewide significance.” Created by the Washington Legislature and U.S. Congress in 1980, WSDOE manages the reserve that protects more than 11,000 acres of intertidal and upland habitat in Skagit County.

Since Padilla Bay is so shallow, the whole bay is intertidal. Low tide exposes miles of mud flats and allows nearly 8,000 acres of eelgrass meadows to grow. These vast eelgrass meadows provide essential foraging habitat for salmon and trap carbon in sediments, keeping it from contributing to climate change.

wetlands are widespread

Whether birdwatching at a local wildlife preserve, breathing the fresh air by the Sound, or strolling by a creek, rest assured the Washington Department of Ecology is working to protect vital wetland resources for current and future generations. Wetlands are widespread across the Salish Sea region, and they are vital for maintaining a healthy, vibrant Salish Sea.

Photo by Nancy Sefton

Curt Hart is a Communications Manager for Washington State Department of Ecology’s Shorelands and Environmental Assistance Program. For 29 years, he has worked as a media relations and outreach specialist for WSDOE and other state agencies and local governments in Washington. He has Bachelor’s Degrees in Journalism, Education, and Political Science, and spends his free time visiting, hiking, mushroom hunting, and backpacking in Washington’s natural areas, especially Puget Sound and Pacific Ocean coast.

Marcus Humberg is a Communications Specialist for the Shorelands and Environmental Assistance Program with the Washington State Department of Ecology. He has worked as a photographer and editor for local and national media outlets, and has helped write, edit, and launch two new websites for Washington state agencies. He has Master’s Degrees in both Public Policy and Strategic Communications, and enjoys hiking and kayaking all around south Puget Sound, especially in and around the Nisqually River delta and wildlife refuge.

Table of Contents, Issue #9, Autumn 2020

From Swamps and Bogs …

by Sara & Thomas Noland, Autumn 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedby Sara & Thomas Noland, Summer 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedWetlands are part of our landscape here in the lowlands near the Salish Sea. Anyone who’s walked around in a...

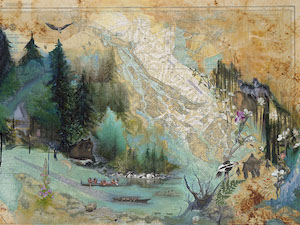

Issue 9 Art Poetry

Autumn 2020Juan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaJuan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaSummer 2020Going Home, painting by Julia MillerComing Home by Dawn Henthorn Salmon come home home to the Elwha. Bit by bit of rubble two feet at a time, the dams were removed,...

Salt Marshes

by Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020Gumweed photo by John F. WilliamsGumweed photo by John F. Williamsby Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020I’ve enjoyed, studied, mapped, and tried to protect wet places for pretty much my entire life. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share some...

Importance of Wetlands

by Josh Wozniak, Autumn 2020 Photographs by John F. Williamsby Josh Wozniak, Summer 2020 Photographs by John F. WilliamsTaking many forms, wetlands are natural features of the landscape that provide crucial functions for both nature and humankind. We benefit directly...

Newts: Wetland Magicians

by Sharon & Paul Pegany, Autumn 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany except as notedby Sharon & Paul Pegany, Summer 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany, except as noted. Did I just see what I think I saw? I had to do a double take while exploring the edge of a local pond...

Earthquakes and Tsunamis

by Carrie Garrison-Laney and Ian Miller Autumn 2020 A photo of sediments in the coastal marsh near the mouth of Salt Creek on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, showing distinct bands of different colors and textures. Photo by Ian Miller.A photo of sediments in the coastal...

10 Things About Duckweed

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as notedby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as noted1. Duckweed grows in dense colonies in quiet water that is undisturbed by wave action. We try to avoid insulting still...

Carpenter Creek Salt Marsh

by Melissa Fleming & Terry Pereida, Autumn 2020 Photos by Terry Pereida, except as notedSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom TwiggSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom Twiggby Melissa Fleming &...

Wetland Basics

Frank Stricklin, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams except as notedThis large wetland in Newberry Hill Heritage Park is listed by the State of Washington as a “wetland of significant conservation value.” It contains many species of aquatic plants, and some...

Blue Carbon

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020Underwater Rainbow, painting by Julia MillerUnderwater Rainbow, painting by Julia Millerby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020As you’ll see everywhere else in this issue, a wetland system isn’t just another lovely place for a nature walk. Wetland...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

FIND OUT MORE

References in article

1989 executive order by the Governor of Washington

About Padilla Bay. Washington State Department of Ecology.

Shorelines of Statewide Significance. Washington State Department of Ecology.

Additional Resources

Some 2020 projects: Hart, Curt 2020. New investments save dynamic coastal wetland habitat. Washington State Department of Ecology.

Floodplains by design: 2020, Washington State Floodplain Manager Discusses Program That’s Helping Communities, Environment. PEW

For a national (US) perspective: Environmental Protection Agency. Wetlands Protection and Restoration

Avoiding & minimizing wetland impacts. Washington State Department of Ecology.

Wetland mitigation resources. Washington State Department of Ecology.