CARPENTER CREEK SALT MARSH

by Melissa Fleming & Terry Pereida, Autumn 2020

Photos by Terry Pereida, except as noted

Salt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom Twigg

Salt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom Twigg

CARPENTER CREEK SALT MARSH

by Melissa Fleming & Terry Pereida, Autumn 2020

Photos by Terry Pereida, except as noted

in early summer

The salt marsh in the Carpenter Creek estuary displays a subtle pattern of colors and textures. The brown pointy tips of Baltic rush (Juncus balticus) mix with the reddish purple stems and green leaves of Douglas aster (Aster subspicatus) in broad swaths of upland, interrupted by crop circle-like swirls of bright green blades of salt grass sticking up among prone stems of the saltmarsh reed (Juncus gerardii) with shiny brown seeds at their tips.

[Click on photo to see the gallery full sized with captions]

Purplish spikes of meadow barley (Hordeum brachyanterum) and clumps of silvery tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa) stand tall between marsh channels, while dark green blades of Lyngby sedge (Carex lyngbyei) form a standing wave at the channel edge.

On the periphery of the upper marsh, soft-stemmed bulrush (Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani), single stems five feet high and thick as a child’s pinkie finger, appear to be leading a stealthy advance away from the forest edge with broadleaf cattails (Typha latifolia) following more cautiously behind. These vegetation patterns reveal the complex interplay of tidal influence and freshwater input that characterize a natural estuary in the Pacific Northwest, where salt and freshwater meet to generate one of the world’s most productive habitats and where terrestrial plants must be able to adapt to fluctuating water and salinity levels that can differ widely across the landscape.

carpenter creek estuary

Conditions in the Carpenter Creek estuary in Kingston, Washington, have not always been natural. South Kingston Road runs across what was once a sand spit that divided the estuary from the rest of Appletree Cove. Not only was water exchange restricted to a culvert under the road, but for a short time in the 1950s, the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife installed a tide gate and cut the entire estuary off from the tides to form a rearing pond for young coho. Further up in the estuary, where the West Kingston Road Bridge stands now, multiple roadbeds were constructed near the lower end of the salt marsh over the last 150 years, most recently with only a five foot diameter culvert allowing Carpenter Creek to flow out, but restricting tidal influence sufficiently that the upper marsh could be used as pasture.

Small “pocket” estuaries like this one were once a common feature in Puget Sound, and are important to young salmon migrating to the ocean from their natal waterways, as stopping places to feed, shelter, grow, and complete the physiological transition from freshwater to saltwater fish. Although Carpenter Creek is a lowland stream and only sees adult cutthroat trout, coho, and the occasional chum during their breeding seasons, five species of juvenile salmonids, including chinook and pink salmon, have been found using the estuary in the spring as one of the last remaining stopping places before the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the ocean beyond. Culverts not only make these habitats less accessible to adult and juvenile fish, but they also reduce the productivity of estuaries by altering their natural hydrology, i.e., restricting the flow of freshwater out and saltwater in.

Stillwaters Environmental Center

In 1999, inspired by the Salmon Recovery Act, two landowners at the head of the salt marsh, Joleen Palmer and Naomi Maasberg, founded Stillwaters Environmental Center with the objective of restoring natural conditions to the lower Carpenter Creek watershed to enhance and restore habitat for salmonids.

With the guidance of county, state and tribal scientists, Stillwaters’ volunteers collected data and lobbied throughout the 2000s in support of the Army Corps of Engineers’ 2006 plan to remove both the South and West Kingston Road culverts. This mission has only recently been realized. In 2012, the ten-foot box culvert under South Kingston Road was replaced with a 90-foot bridge, and in 2018, the five foot diameter pipe at West Kingston Road was replaced with a 150-foot bridge.

This gallery of photos shows the box culvert that was removed (2011), some of the bridge construction (2011), and the new bridge (2012). Photos by John F. Williams

Stillwaters was tasked with ten years of post-construction monitoring after each bridge, giving us the opportunity to document the recovery of the lower watershed with a team composed of a few staff members, dozens of volunteers and college interns, and hundreds of supporters in North Kitsap and beyond. By annually mapping the distribution of plant species and the salinity of the water around their roots, we hope to document how unrestricted tidal exchange and unimpeded creek flow simultaneously affect these plant communities over time.

salt marsh plants

To be successful in a salt marsh, plants must be able to tolerate being all or partially submerged in water once or twice a day for minutes or hours at a time when the tide comes in, as well as being fully exposed to drying in the open air when the tide goes out. This is a very different challenge than what freshwater marsh plants typically experience: water levels that change gradually over longer periods of time (e.g., seasonally), if at all. Salt marsh plants must also tolerate higher levels of salt, not just while inundated by tides, but even after the tide recedes.

Particularly during the summer, water remaining in the soil evaporates leaving salt behind. Over time, this can cause more salt to build up in the soil higher in the marsh than in lower lying regions where tidal exchange flushes the soil more frequently. However, in pocket estuaries like Carpenter Creek’s, multiple freshwater inputs contribute additional complexity to the ecosystem by diluting some higher elevation soils (for example, along the creek and along the marsh edges) via direct run-off and seepage from surrounding hillsides. Wide variations in pore water salinity and duration of inundation across the Carpenter Creek salt marsh create an intricate pattern of color and texture in the marsh.

Looking South at West Kingston bridge from above Stillwaters Environmental Center. Photo by Tom Twigg

how to get there

In normal times, Stillwaters would be welcoming volunteers to come learn about the lower Carpenter Creek ecosystem firsthand and participate in all of our monitoring and studies. But these are not normal times. We hope to welcome volunteers back in small numbers soon. Meanwhile, you can visit the estuary and salt marsh via Arness Park on Appletree Cove in Kingston. At low tide (less than five feet), people can walk up the creek channel through the mudflats, and at high tide (greater than 10 feet) you can take a kayak all the way up into the salt marsh. There are two good viewpoints. From the South Kingston Bridge you can see the eastern lobe of the the lower estuary. From the West Kingston Bridge you can view the salt marsh to the north and western lobe of the lower estuary to the south. Herons, eagles, osprey, waterfowl, otters, and deer may be present throughout the year, and coho salmon may be seen in the fall at the appropriate tide heights.

Looking East toward Kingston and the ferry terminal in the distance, the West Kingston bridge is in the lower right and points toward the South Kingston Bridge (AKA Stillwaters Fish Passage) and Arness Park. Photo by Tom Twigg

Melissa Fleming, Ph.D., Program Director at Stillwaters Environmental Center, received the science reins from founding partner Joleen Palmer in January 2020. Melissa earned her doctorate from UW in Animal Behavior, has taught several undergraduate research courses, and did post-doctoral fellowships at University of Alaska, Fairbanks and at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. She subsequently worked in conservation genetics studying endemic mammals of the North Pacific coast. She’s lived in Kitsap County since 1999 with her husband, John Ellsworth, and their daughter Katherine (Kit). She is a life-long learner who has thoroughly enjoyed her immersion into environmental science since joining Stillwaters in early 2018.

Terry Pereida, Administrative Director, received the business reins from founding partner Naomi Maasberg the first of May. Terry grew up on California’s central coast and earned her degree in Communication Studies from UC Santa Barbara.

Terry worked in aerospace and then technology before going back to school for her teaching credentials and taught in the classroom at the high school level for 20 years. She and her husband, Dano, moved to Kingston recently from Kailua-Kona, Hawaii and survived their first real winter here. Terry and Dano love experiencing nature’s seasons in Washington and look forward to meeting their Kingston neighbors in the community.

Table of Contents, Issue #9, Autumn 2020

From Swamps and Bogs …

by Sara & Thomas Noland, Autumn 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedby Sara & Thomas Noland, Summer 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedWetlands are part of our landscape here in the lowlands near the Salish Sea. Anyone who’s walked around in a...

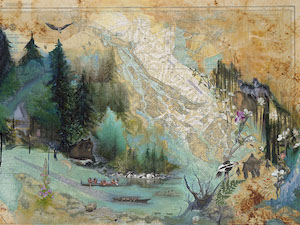

Issue 9 Art Poetry

Autumn 2020Juan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaJuan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaSummer 2020Going Home, painting by Julia MillerComing Home by Dawn Henthorn Salmon come home home to the Elwha. Bit by bit of rubble two feet at a time, the dams were removed,...

Salt Marshes

by Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020Gumweed photo by John F. WilliamsGumweed photo by John F. Williamsby Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020I’ve enjoyed, studied, mapped, and tried to protect wet places for pretty much my entire life. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share some...

Importance of Wetlands

by Josh Wozniak, Autumn 2020 Photographs by John F. Williamsby Josh Wozniak, Summer 2020 Photographs by John F. WilliamsTaking many forms, wetlands are natural features of the landscape that provide crucial functions for both nature and humankind. We benefit directly...

Newts: Wetland Magicians

by Sharon & Paul Pegany, Autumn 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany except as notedby Sharon & Paul Pegany, Summer 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany, except as noted. Did I just see what I think I saw? I had to do a double take while exploring the edge of a local pond...

Healthy Wetlands

by Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Autumn 2020Wetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. WilliamsWetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. Williamsby Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Summer 2020For the 4.2 million residents in and around Puget Sound, there is a good...

Earthquakes and Tsunamis

by Carrie Garrison-Laney and Ian Miller Autumn 2020 A photo of sediments in the coastal marsh near the mouth of Salt Creek on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, showing distinct bands of different colors and textures. Photo by Ian Miller.A photo of sediments in the coastal...

10 Things About Duckweed

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as notedby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as noted1. Duckweed grows in dense colonies in quiet water that is undisturbed by wave action. We try to avoid insulting still...

Wetland Basics

Frank Stricklin, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams except as notedThis large wetland in Newberry Hill Heritage Park is listed by the State of Washington as a “wetland of significant conservation value.” It contains many species of aquatic plants, and some...

Blue Carbon

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020Underwater Rainbow, painting by Julia MillerUnderwater Rainbow, painting by Julia Millerby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020As you’ll see everywhere else in this issue, a wetland system isn’t just another lovely place for a nature walk. Wetland...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.