WETLAND BASICS

Frank Stricklin, Autumn 2020

Photos by John F. Williams except as noted

This large wetland in Newberry Hill Heritage Park is listed by the State of Washington as a “wetland of significant conservation value.” It contains many species of aquatic plants, and some threatened plants. Photo by Frank Stricklin.

This large wetland in Newberry Hill Heritage Park is listed by the State of Washington as a “wetland of significant conservation value.” It contains many species of aquatic plants, and some threatened plants. Photo by Frank Stricklin.

WETLAND BASICS

Frank Stricklin, Summer 2020

Photos by John F. Williams except as noted

Whether you call it a pond or a swamp, basically a wetland is a shallow lake — shallow enough that sunlight can reach the depths and make wetlands magical places in our Salish lowlands. These shallow waters are teeming with the ebb and flow of life. They draw us to their shorelines where we can pause, contemplate, and observe a diverse array of wildlife and plants.

On warm summer evenings at twilight hundreds of bats swarm over the surface catching insects. During the day it is the swallows’ turn to feed on the abundant mosquitoes and mayflies emerging from the pond, while fish and amphibian larvae feed on tiny creatures below the surface. In late winter, waterfowl raft on the quiet waters to rest and feed until time to migrate farther north to nest. Raptors use the standing dead trees near the shore to watch for a meal, while woodpeckers and cavity-nesting birds use them for nesting or as a food source. Beaver, river otter, and other mammals can be observed on occasion. If we can sit still long enough, we could be rewarded with a bear or bobcat sighting.

See the Barn Swallow article for more about them.

See the Barn Swallow article for more about them.

Wetland habitats support and nurture a wide variety of species that includes humans as one of the many threads that form a web of life. But what you can’t see is one of the most important features of a wetland.

photosynthesis

It is here in these wetlands that the energy of sunlight converts atmospheric carbon dioxide and water to solid matter — food for both plants and animals. We all learned about photosynthesis in grade school: sunlight and atmospheric carbon dioxide interact with the plant’s chlorophyll to produce sugars and other carbon-based substances that nourish and sustain plant life. Shallow water allows photosynthesis to occur throughout the water column from the surface to the bottom. Water-loving plants, which may be free-floating at the surface (e.g., duckweed) or rooted in the muck (e.g., water lilies), along with algae in the water column, make these waters comparable in productivity to tropical rainforests.

See more about the plants that inhabit wetlands in the article From Swamps and Bogs to Marshes and Meadows.

See more about the plants that inhabit wetlands in the article From Swamps and Bogs to Marshes and Meadows.

Through photosynthesis, these plants store carbon and release oxygen in just one of a complex array of services provided by wetlands. Contrast a wetland to a lake, where a lake’s greater depth prevents sunlight from reaching the bottom, and photosynthesis is limited to the shallows near the shore.

water storage

Also important is the water storage service that wetlands and beaver ponds provide for a wide variety of living things that require stored, open, or flowing water for their existence. The Puget Lowlands are soaked by between 30 and 80 inches of rainfall each year, mostly from October through April. This rain recharges the porous glacial soil “sponge” that slowly releases a supply of water that becomes streamflow throughout the rain-free months of summer.

Wetland ponding keeps the water table closer to the surface through the summer and allows a quicker return of surface flows critical to salmonids (a family of cold-water fishes, including salmon, trout, chars, freshwater whitefishes, and graylings) once the rains return in October. The more water retained (less runoff), the better. If the water table is three feet below the surface by August, it will take several weeks of rainfall to bring it back to the surface where intermittent streams can begin to flow. If it is at or near the surface, flow can begin with the first heavy rains of fall. These could be critical weeks for salmonids and other species that use the wetlands and intermittent streams to reproduce and rear young.

More than salmon use our wetlands for survival. This pair of Western Brook Lamprey were filmed underwater mating in an un-named tributary to Wildcat Creek. They will lay between 10 and 15 thousand eggs and then die. The young will drift downstream and hopefully end up where they will thrive. Photo by Frank Stricklin.

Coho salmon in a stream near a culvert.

wetland nurseries

All salmonids require stream flow at some life stage. Chum salmon generally use the larger rocks found lower in our watersheds to lay eggs. The fish hatch and head to near-shore salt water habitats (estuaries) right away. This strategy works well when heavy fall rains arrive on schedule. However, coho salmon and sea-run cutthroat trout utilize the intermittent streams found in upper reaches of our watersheds to lay eggs. Once hatched, the fry must reach wetlands where they will spend about fifteen months maturing before fall rains flush them out to sea. They must find sanctuary before their natal stream dries up for the summer. Their odds of survival are greatly increased if they reach the safety of a wetland where they have deeper water, cover, and abundant food. The large and small woody debris found in wetlands provide cooling shade and a place to hide from predators.

Glass and metal sculpture near the mouth of Clear Creek in Silverdale, WA.

newberry hill heritage park

When people ask me, “Why did we spend all this money on a bridge, when there is no water here?” I reply, “There will be salmon here,” while pointing at this dry streambed in August. For more information about this bridge construction and the volunteers who helped make it happen, visit www.friendsofnhhp.com, where you’ll also find a map of hiking trails through this beautiful park.

If wetlands are your favorite part of our home surrounded by the Salish Sea, don’t forget that without the upland forests to protect the wetlands from our unintended insults and intrusions, there will be no healthy wetlands. We must all think on the landscape scale, and steward the entire system, not just our favorite part.

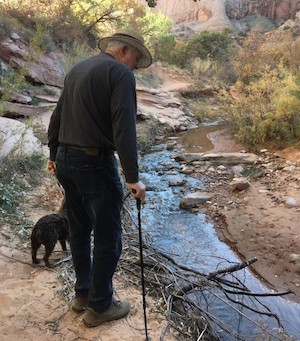

The author, seated, and Arno Bergstrom standing at the fish passage bridge installed in Newberry Hill Heritage Park in fall 2019. Now we need rain! Photo courtesy Karl Erickson. Read the article by Arno in Issue 2 of Salish Magazine.

Robert Frank Stricklin

Certified by Washington Department of Ecology in wetland rating for Eastern and Western Washington State. Associate in Science and Technology (1975) Certified Metrologist (National Institute of Standards and Technology) for US NAVY and Lockheed Martin Missiles and Space. State of Washington Wildlife Conservation award winner (WDFW). WSU Stream Steward and Native Plant Advisor. Wetland Steward for Newberry Hill Heritage Park. Lifelong learner.

Table of Contents, Issue #9, Autumn 2020

From Swamps and Bogs …

by Sara & Thomas Noland, Autumn 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedby Sara & Thomas Noland, Summer 2020 Photos by Thomas Noland except as notedWetlands are part of our landscape here in the lowlands near the Salish Sea. Anyone who’s walked around in a...

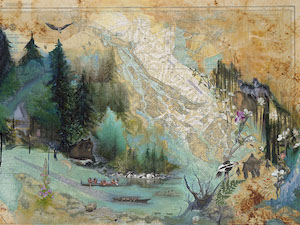

Issue 9 Art Poetry

Autumn 2020Juan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaJuan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaSummer 2020Going Home, painting by Julia MillerComing Home by Dawn Henthorn Salmon come home home to the Elwha. Bit by bit of rubble two feet at a time, the dams were removed,...

Salt Marshes

by Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020Gumweed photo by John F. WilliamsGumweed photo by John F. Williamsby Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020I’ve enjoyed, studied, mapped, and tried to protect wet places for pretty much my entire life. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share some...

Importance of Wetlands

by Josh Wozniak, Autumn 2020 Photographs by John F. Williamsby Josh Wozniak, Summer 2020 Photographs by John F. WilliamsTaking many forms, wetlands are natural features of the landscape that provide crucial functions for both nature and humankind. We benefit directly...

Newts: Wetland Magicians

by Sharon & Paul Pegany, Autumn 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany except as notedby Sharon & Paul Pegany, Summer 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany, except as noted. Did I just see what I think I saw? I had to do a double take while exploring the edge of a local pond...

Healthy Wetlands

by Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Autumn 2020Wetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. WilliamsWetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. Williamsby Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Summer 2020For the 4.2 million residents in and around Puget Sound, there is a good...

Earthquakes and Tsunamis

by Carrie Garrison-Laney and Ian Miller Autumn 2020 A photo of sediments in the coastal marsh near the mouth of Salt Creek on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, showing distinct bands of different colors and textures. Photo by Ian Miller.A photo of sediments in the coastal...

10 Things About Duckweed

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as notedby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as noted1. Duckweed grows in dense colonies in quiet water that is undisturbed by wave action. We try to avoid insulting still...

Carpenter Creek Salt Marsh

by Melissa Fleming & Terry Pereida, Autumn 2020 Photos by Terry Pereida, except as notedSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom TwiggSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom Twiggby Melissa Fleming &...

Blue Carbon

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020Underwater Rainbow, painting by Julia MillerUnderwater Rainbow, painting by Julia Millerby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020As you’ll see everywhere else in this issue, a wetland system isn’t just another lovely place for a nature walk. Wetland...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.