WHY DO WE THIN FORESTS?

by Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

WHY DO WE THIN FORESTS?

By Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

have you noticed how the forest changes as you follow the trail?

If you’ve walked through one of the many forested areas that are open to the public around Puget Sound, you may have noticed the “look” of the forest change suddenly as you followed a path. If you haven’t noticed different forest “looks,” keep you eyes peeled next time you venture into the forest.

A large percentage of our public lands were once industrial tree farms where Douglas fir trees were densely planted, then harvested for wood products. These plantations kept vast acreages in the “young forest” stage of densely packed Douglas fir trees, between 10 and 80 years old, with very little else growing because so little sunlight was able to penetrate the tree canopy.

See comparative canopy photos in Forest Stages in this issue.

See comparative canopy photos in Forest Stages in this issue.

This offered poor wildlife habitat and posed higher risks for disease and fire.

In areas that are now parks or preserves, the new goal is to improve the ecological diversity so that the repurposed tree farms can more quickly develop into healthy, habitat-rich forests.

A good example is found in Kitsap County, which lies between Seattle and the Olympic Peninsula. Since 2000, the county has added over 8,000 acres of protected forest lands, for a total of 11,000 acres. The average age of trees in these areas, mostly Douglas Fir, is less than 40 years.

A management technique called variable density thinning is being used in some of these areas which, coupled with other restoration efforts such as plantings, will accelerate the transition from young forest stage to include the wider array of biodiversity associated with more mature forests.

Variable density thinning is just what it sounds like: the average space between trees is increased, but the density is not uniform. In some small areas the higher density is retained, in other areas trees are removed to lower the density, and some small clearings are also created.

thinning process video by Arno Bergstrom

After the felled trees are delimbed, the machinery used for the thinning drives over the branches and culled wood chunks scattered through the area, pressing them close to the ground. This encourages decomposition, reduces fire risk, and creates new habitats for wildlife.

After the felled trees are delimbed, the machinery used for the thinning drives over the branches and culled wood chunks scattered through the area, pressing them close to the ground. This encourages decomposition, reduces fire risk, and creates new habitats for wildlife.

Birds will start foraging almost immediately in the freshly disturbed soil and forest floor. Within two to three years after variable density thinning, understory plants develop, encouraged by the increase in light reaching the ground. Among the first arrivals are the northwest’s native ferns. Eventually, salal, huckleberries, nettles, salmonberries, and others will put in an appearance and birds and other animals will become more abundant as the understory plants flourish.

The trees themselves develop more roots, branches and leaves as they take advantage of available light, moisture, and nutrients. It takes eight to ten years before more rapid increases in their girth and height show as obvious responses to the thinning process.

photo by Nancy Sefton

Of the 11,000 acres now part of the Kitsap County Heritage Park system, 9,000 are in the young forest stage. About 2,000 acres are in the mature forest stage, and fewer than 100 forested acres are in the old forest stage. (See the article on Forest Stages.) It’s similar in the Puget Sound region as a whole: most of the retired tree farms are in the young forest stage. There are a few places in the Puget Sound lowlands where you can see some “mature forests”, and even fewer where you can see “old growth.” But generations from now, people in this region will be able to enjoy the benefits of nature’s form of maximum maturity — this “old forest stage” takes 200 years or more to develop.

So when you see evidence of forest thinning, it may be former tree farms being revitalized and boosted on their way to becoming healthier, older forests that will benefit wildlife and future generations of park patrons. It also gives you a chance to examine the rings on recently cut trees.

For more about that see Tree Rings in this issue.

For more about that see Tree Rings in this issue.

But just when you think you understand the various stages of the forest, keep exploring and you’ll find outliers.

Here are two examples of unusual sights in the forest.

The presence of a gnome kept the forest around it dark and without much growing on the ground, but in the distance, some light penetrates a less dense forest.

These trees were planted in long rows, spaced far enough apart that bushes and small trees could sprout up between them.

Arno Bergstrom, Kitsap County Community Forester was Extension Forester with Washington State University for 35 years; created and delivered the Forest Stewardship Coached Planning curriculum to over 1,800 family forest landowners. He currently works with citizens and stakeholders implementing ecological forest management projects on 11,000 acres of forested park land owned by Kitsap County. “My goal is to transform Kitsap County parks, that were former industrial tree farms, into biologically rich, resilient and complex ecosystems that benefit the community, people and wildlife. “

Nancy Sefton is an artist, writer, videographer and photographer who specializes in nature subjects. As a former diver she has contributed frequently to national magazines and newspapers, publishing over 300 articles about marine life. Nancy now lives in Poulsbo and writes for Sound Publishing newspapers.

Table of Contents, Issue #2, Winter 2018

Forest Stages

Photo Essay by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedPhoto Essay By John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedwhy does the forest occasionally change character as you travel...

Stump Stories

Photo Essay by Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedtrees dieMaybe they die...

Rings

Musings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedMusings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedTree rings can be counted when a recently cut tree is encountered in...

Who Cooks

by Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedphoto by Nancy Seftonphoto by Nancy SeftonBy Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noteda family of barred owls flew into my neighborhoodI...

Nurse Log

by Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 photo by John F. WilliamsBy Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 above photo by John F. WilliamsFallen trees and decaying stumps lie on the forest floor in the midst of their thriving offspring. Much like beloved elders gone before, the trees on...

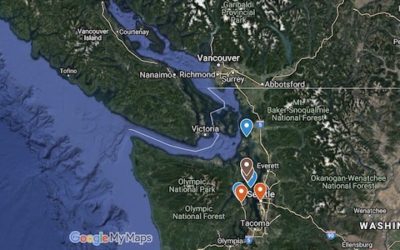

Map-2

Winter 2018Winter 2018The button below will open a Google map with some markers to show the locations of landmarks related to topics discussed in this issue #2 of Salish Magazine. For example, you can find some parks where you can see big, old stumps or different...