"WHO COOKS FOR YOU?"

by Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

photo by Nancy Sefton

photo by Nancy Sefton

"WHO COOKS FOR YOU?"

By Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

a family of barred owls flew into my neighborhood

I first noticed them from their raucous calls in a nearby tree. Who cooks for you? Who cooks the food? I ran outside to see two owls fly from the tall Douglas fir next door, across the neighbor’s yard, to the next street over. I was thrilled to have owls so near my home. I stood listening as the last of the daylight disappeared and wondered if anyone else had noticed the owls calling.

Who cooks for you? Who cooks the fooood? called the first owl. Then a more distant owl responded, who cooks the fooood? The pair called back and forth for almost an hour. I tried to guess at their mid-summer conversation.

Barred Owl Call

Barred owls mate for as long as they survive, but this didn’t sound like two adults to me. From the intermittent, hissing screeches of a young barred, it sounded like one of the owls was begging for food. After the chicks fledge, the mother owl flies off to replenish her reserves, leaving the father to care for the young and teach them how to hunt. From the sounds of it, one of the owls was refining its hunting skills, while the patient father encouraged the efforts. The pair flew to another yard over the hill. As the stars brightened, I could hear the now distant conversation. For the next several nights, I heard the barreds in the same Douglas fir, calling at dusk. Each time, I stopped to listen.

Barred owls are quite striking to look at. It’s the dish-shaped face of the owl that first captures the owler’s attention with large, dark, knowing eyes and a sharp yellow beak. Alternating brown and white concentric circles frame the face, while brown-and-white horizontal bars create a hood-like pattern over the head and neck, as if the barred is wearing a scarf. On the chest are the vertical brown bars for which the “barred” owl gets its name. A long brown-and-white tail hangs below the branch, as sharp, black, inch-long talons grip tight.

Like all owls, the barred owl has evolved over millennia to be a top avian predator. Owl eyes, power-packed with black and white nerve cells called rods, gather every shred of light in the darkness of night. Bats leaving their roosts in a nearby woodpile—for us just a part of the forest backdrop—on their nightly search for mosquitos and other flying insects, become prey for the nocturnally-sighted barred owl.

The dish-shaped face funnels the softest of sounds to the owl’s ears, placed one higher than the other on either side of the head. These asymmetrical ears allow for a swift and efficient strike from above when the barred owl triangulates the exact position of a sharp chirp from a distressed red-backed vole sifting through the detritus of the forest floor, looking for seeds and fungi. And the zygodactyl talons of the owl—two toes pointing backward, one forward and one movable talon like an opposable thumb—enable the owl to grab and squeeze a hapless deer mouse.

Kylie Stoneburner from West Sound Wildlife Shelter shows off a Barred Owl. Note the talons.

Don’t be fooled by the amazing closeup photos elsewhere in this article — often one needs to look carefully to see owls in the woods. They might be sitting in a tree quite some distance from the trail. Or if they fly past, it’s often so quickly there’s barely time to look up.

Barred owls are relative newcomers to the Pacific Northwest. Over the last one hundred years, they have moved here like many of us, and theories abound about how and why barred owls emigrated from eastern North America. One theory speculates that it was the result of European settlement. In the late 1800s, white settlers headed west, expanding the boundaries of the nation. As they settled the northern Great Plains, they pushed Native Americans off the land, claiming the territory for farms and homesteads. They also ended the Native American practice of burning the prairies, allowing trees to grow where none had grown before. They planted trees too and altered the habitat forever.

Following the lush green habitat bridge created by this westward movement, possibly as early as the 1920s,

barred owls—the more aggressive, slightly larger cousin of the northern spotted owl—moved west. Being highly adaptable to a wide variety of habitats, including both the pristine old-growth and clearcut forests, barred owls thrived here.

The clearcut forests may have also inadvertently provided barred owls with protection from their fiercest predators, the great horned owls and northern goshawks that prefer forests, as opposed to clearcut land, for foraging. Eventually, the barred owls found an almost empty niche left vacant by the near extinction of the spotted owl. The barreds claimed territories and began pushing the last native spotted owls out of their preferred habitat, the remaining old-growth forests teeming with prey.

Another theory suggests that barred owls may have moved naturally into the Pacific Northwest from Canada. By overcoming biological hurdles and expanding into the evergreen forests of eastern Canada, they made their way west following the arc of Canada’s boreal forests. They were first documented in British Columbia in 1943, with the first nesting pair spotted in 1946. They were seen in Western Washington in 1969. By 1979 they had spread into Oregon, and into California by 1985, dispersing naturally and normally as part of the species’ successful growth and expansion as a predator rather than as a result of human interference.

On Bainbridge Island, barred owls were first seen in 1992. Little more than twenty years later, in 2014, citizen scientist and owl biologist, Jamie Acker, monitored thirty-five to forty-five nesting pairs there. Now in 2018, barred owls are considered by some to be an invasive species, unwelcome in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Barred owls are the opportunists of the owl world. Like coyotes and glaucous gulls, barred owls are not picky about what they consume. As medium-size owls which weigh, on an average, slightly over two pounds, and have a wingspan of three and a half feet, are cosmopolitan hunters, feeding on a variety of small animals and owls, such as northern saw-whet owls, northern pygmy owls, and western screech owls.

artwork by Nancy Sefton

This owl was staring intently at the blackberry bushes. Closer inspection revealed that it was staring at a squirrel eating blackberries, perhaps waiting for the squirrel to wander far enough away from the bush to become an easy meal.

This owl was staring intently at the blackberry bushes. Closer inspection revealed that it was staring at a squirrel eating blackberries, perhaps waiting for the squirrel to wander far enough away from the bush to become an easy meal.

In 2009, Acker saw his last western screech owl on Bainbridge Island. These small owls hatch and fledge at the same time that barred owls are looking for food for their own growing chicks. The young owls, called “branchers” before they fledge, sit on a branch near the nest and cry for food, making them easy targets for barred owls. Eastern screech owl chicks do not behave in this way because in the east, the two species have evolved together. The eastern screech owls have had time to learn what works for their survival and what does not.

In the Pacific Northwest, we don’t have the luxury of time when it comes to threatened species. Barred owls seem to be doing their best to claim the old-growth territory from the threatened northern spotted owl. And therein lies the problem.

Dave Wiens, a wildlife biologist with the USGS in Corvallis, Oregon, studied the competition between northern spotted owls and barred owls for his PhD dissertation at Oregon State University. He found a high level of competition between the two species, with barred owl pairs outnumbering the less aggressive northern spotted owl pairs by four to one. He also estimated that northern spotted owls require about two to four times the area per home range of barred owls—4,554 acres to 1,435 acres, or seven-square miles to 2.24-square miles, respectively.

To complete his study, he radio-tagged twenty-nine spotted owls and twenty-eight barred owls in a 463-square-mile study area and followed them for two years, from 2007 to 2009. He studied how these species use their territory, what type of habitats each species chooses, what they eat, and survival and reproductive rates. The diet of barred and spotted owls is similar in that both prefer woodrats, hares and flying squirrels that live in tree cavities in old-growth forests where the trees are close enough together to soar between, as flying squirrels do. These species that account for 81 percent of a northern spotted owl’s diet only take up 49 percent of a barred’s menu. On one day during his study, Wiens got a first-hand look at the variety in a barred owl’s diet. While observing a radio-tagged female barred owl sitting in a tree above a shallow pool, he saw the owl drop down to catch crayfish, one after another, with no need to move beyond the tree at all. He watched other pairs of barreds doing the same thing.

photo by Nancy Sefton

They also caught insects, salamanders, and frogs—creatures that also did not evolve alongside these nocturnal avian predators. Barred owls, it seems, are outcompeting many species in the Pacific Northwest.

Yet in all the time Wiens spent watching the barred owls during his two-year study, he couldn’t help but get to know the individual personalities of the owls. “I have a huge amount of respect for both species [of owls], especially the barred owls,” he said. “They’re an impressive species. Very intelligent and adaptive.”

It may matter only to us humans as we try to save the spotted owls from certain extinction, but if we label the barred owls as invasive, as interlopers who do not belong in our woods, it becomes easier to remove them. Some have suggested this and are currently actively experimenting with removal of barred owls from forests to save the spotted owl.

If they have arrived naturally, as part of nature’s plan to evolve and expand, then removing them becomes a more complex moral dilemma.

I listened to these barred owls calling near my home in Suquamish, Washington, homeland of Chief Sealth, better known as Chief Seattle. He famously called for us all to remember to live with the land and its creatures, because each strand in the tapestry of life is as important as the next to the whole. Only now, in these early years of the twenty-first century, are we beginning to understand through careful study of natural systems just how these threads in the tapestry are interwoven. But we are studying the broken remains of a once-stable system thousands of years old. Now, with these forests in an ever-changing state of flux, how can we ever know which strands are safe to pull? I watch the beautiful barred owl flying from tree to tree through my neighborhood. However they arrived, they are now members of the web of life in the Pacific Northwest.

Leigh Calvez is a naturalist and nature writer. She studied humpback whales in Massachusetts and on Maui, Hawaii along with spinner dolphins on the Big Island of Hawaii. As a naturalist, she has led whale watching tours around the world to places like the Azores, New Zealand and British Columbia. Her interest in the natural world led her to nature writing and her first book “The Hidden Lives of Owls: The Science and Spirit of Nature’s Most Elusive Birds”. Leigh’s essay about her adventures in the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia was published in “American Nature Writing 2003” by Fulcrum Books. Her work was also published in an anthology for Sierra Club Books entitled “Between Species: Celebrating the Dolphin-Human Bond”. Leigh’s essays have also appeared in Smithsonian Magazine, High Country News, The Ecologist, Ocean Realm, The Christian Science Monitor, The Seattle Times and The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Her second book, “The Breath of a Whale: The Science and Spirit of Pacific Ocean Giants,” from Sasquatch Books was just released in March 2019.

Table of Contents, Issue #2, Winter 2018

Forest Stages

Photo Essay by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedPhoto Essay By John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedwhy does the forest occasionally change character as you travel...

Why Thin

by Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedhave you noticed how the forest changes as you follow the...

Stump Stories

Photo Essay by Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedtrees dieMaybe they die...

Rings

Musings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedMusings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedTree rings can be counted when a recently cut tree is encountered in...

Nurse Log

by Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 photo by John F. WilliamsBy Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 above photo by John F. WilliamsFallen trees and decaying stumps lie on the forest floor in the midst of their thriving offspring. Much like beloved elders gone before, the trees on...

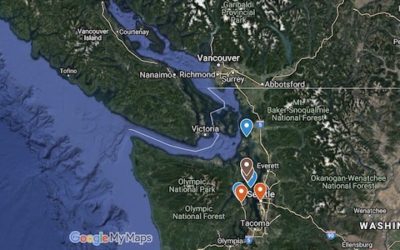

Map-2

Winter 2018Winter 2018The button below will open a Google map with some markers to show the locations of landmarks related to topics discussed in this issue #2 of Salish Magazine. For example, you can find some parks where you can see big, old stumps or different...