VISIBLE FOREST STAGES

Photo Essay

by John F. Williams, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

VISIBLE FOREST STAGES

Photo Essay

By John F. Williams, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

why does the forest occasionally change character as you travel down a path?

Once a major part of our Salish Sea lowlands, timber mills have been disappearing, and timber companies (and other commercial interests such as Washington’s Department of Natural Resources) have been divesting some of their holdings. This means that quite a bit of timberland is being made available for development, for preserves, and for parks.

This issue of Salish Magazine focuses on those forested areas in the Salish Sea lowlands that were once industrial tree farms and are now open to the public. Some are still private land, and some have been acquired by municipalities or conservation organizations.

Ages of the trees, management strategies, and growing conditions have led to patches (or stands) of trees that are different in appearance from neighboring stands. Sometimes, on a single expedition, you might see the character of the forest change several times. These are clues to the stories you might find if you examine things closely. By observing these characteristics of the forest, you can learn something about its history, future, and about what day-to-day life is like in that particular patch of woods.

Here is a photo essay showing some of the kinds of tree stands you might see when you walk in these areas.

After a clearcut, seedlings are planted. In this region, Douglas fir is the most common type of tree planted and the young preforest looks very green, like a Christmas tree lot.

Before thinning, the canopy is so dense that little sunlight penetrates.

young forest stage

Somewhere between 15 and 30 years after the trees are planted, the tree canopies become so dense that very little sunlight reaches the ground. That makes it difficult for plants to grow between the trees. And as the trees grow taller, they shed their lower branches which were prevented from receiving light by the dense canopy.

When the forest is dense and uniform like this it is called the “young forest” stage

But trees and other plants keep producing seeds, so sometimes you might see some smaller trees mixed among the older ones. These areas will typically be thinned to remove the smaller than desired trees, increasing spaces in the canopy to promote faster growth of the remaining more commercially valuable trees. You might see lots of the smaller trees lying on the ground for years after such a procedure.

Commercially thinned young forests still retain a relatively “uniform” look

After thinning, the canopy has openings that allow sunlight into the forest.

Another type of forest you might see with uniform sized trees has both small and large gaps scattered between the trees, and even the occasional clearing. These forests represent a fairly new (in tree years) management strategy called variable density thinning. This thinning process is often accompanied by the planting of diverse species in order to help a retired tree farm more quickly turn into a healthy ecosystem.

As time goes on, a young forest subjected to variable density thinning begins to show some of the diversity characteristics of a more mature forest.

For more about thinning, see Why Thin Forests? in this issue

For more about thinning, see Why Thin Forests? in this issue

mature forest stage

After about 100 years of uninterrupted growth, or less if variable density thinning is involved, there will be a mix of tree species and sizes, a lot of fallen and rotting wood on the ground, and a wide diversity of spacing between the trees. An area like this, called a “mature forest,” is beginning to be a richer ecosystem and is on its way to becoming an old growth forest again. Today, this mature stage is not common in our Pacific Northwest lowlands, but many of our young forests are being allowed to age so that they will become mature forests in future decades.

This small area in Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park has not been logged for about 80 years, and it’s beginning to look like a “mature forest.”

old forest stage

In simple terms, an Old Forest is an area that has been growing and evolving for 200 years or more, and it has achieved considerable diversity of tree age, species, size, spacing, and ecosystem function. There is a substantial population of old trees with some of the features that only old trees can offer, such as a mature canopy ecosystem and holes and crevices for various kinds of creatures to call home. Additional habitat and other services are provided by very large and copious dead wood. The Stump Stories article discusses some of the important roles that dead wood plays.

A relatively small stand of trees in Deception Pass State Park is designated an “old growth” area.

There aren’t many old growth areas like this around Puget Sound, but there are a few small ones. And this old forest stage is the long term goal for the management of conservation lands and parks that are retired tree farms.

”Field Guide to Old-Growth Forests” by Larry Eifert is a really excellent overview of old-growth forests and their inhabitants, and it also points out where some might be seen in the Pacific Northwest.

wetlands

Yet another type of forest is perhaps better described as wetlands — stands of mainly alders and cedars that grew in the wetter areas that weren’t practical for Douglas fir harvests. These wetlands are another kind of key habitat, and there will be plenty about wetlands in future issues.

Now that you’ve seen a quick overview of the stages a forest goes through, watch for these stages as you’re traveling along a trail. Other articles in this issue and in future issues will refer to these stages as they explore the different sights and sounds of the forests. For example

the “Why Thin” article in this issue explains the process called variable (or restorative) thinning which hastens the progress of the young forests becoming old forests again.

the “Why Thin” article in this issue explains the process called variable (or restorative) thinning which hastens the progress of the young forests becoming old forests again.

photo by Nancy Sefton

John F. Williams, publisher of Salish Magazine: over decades of exploring underwater and in our forests and beaches, my experiences have been enriched by the insights of knowledgeable people. What I learned from them dramatically changed the way I see things,

I shared those insights by making educational films and through lecture tours. Now, I’ve created Salish Magazine to extend that notion of sharing insights by offering a wealth of articles that are keyed to the observable, but pull back the curtains to reveal the invisible.

Table of Contents, Issue #2, Winter 2018

Why Thin

by Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedhave you noticed how the forest changes as you follow the...

Stump Stories

Photo Essay by Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedtrees dieMaybe they die...

Rings

Musings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedMusings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedTree rings can be counted when a recently cut tree is encountered in...

Who Cooks

by Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedphoto by Nancy Seftonphoto by Nancy SeftonBy Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noteda family of barred owls flew into my neighborhoodI...

Nurse Log

by Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 photo by John F. WilliamsBy Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 above photo by John F. WilliamsFallen trees and decaying stumps lie on the forest floor in the midst of their thriving offspring. Much like beloved elders gone before, the trees on...

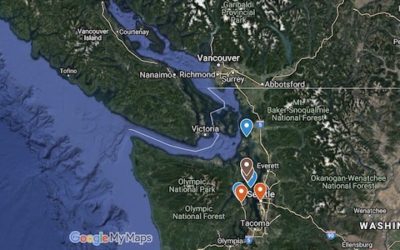

Map-2

Winter 2018Winter 2018The button below will open a Google map with some markers to show the locations of landmarks related to topics discussed in this issue #2 of Salish Magazine. For example, you can find some parks where you can see big, old stumps or different...

FIND OUT MORE

Eifert, Larry, Field Guide to Old-Growth Forests (2000).