STUMP STORIES

Photo Essay

by Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

STUMP STORIES

By Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

trees die

Maybe they die from old age, maybe from being blown down by a storm, or from disease, or perhaps they were harvested. Except when harvested, the trees remain in the forest, and over a period of decades or centuries they are an active part of the forest ecosystem. This old wood eventually breaks down, but that doesn’t just magically happen on its own; it gets lots of help. Dead wood in the forests is home for creatures such as small mammals, birds, insects, and amphibians. It is a substrate for lichen, ferns, and moss. It is food for detritus eaters and bacteria, and apartment buildings for mushrooms.

Where trees haven’t been harvested, fallen logs play an important role in the forest ecosystem.

And in the process of making themselves at home, these creatures gnaw, eat, dissolve, or otherwise transmogrify the wood at many different spatial and temporal scales simultaneously — it will take perhaps hundreds of years for a large log to turn into dirt, but it doesn’t take very long for a slug to chew up a fleshy mushroom that is slowly eating the log. Rodents excavate holes and tunnels, and they also make use of excavations made by previous generations of rodents — at least as long as they manage to escape the talons of the owls in the forest.

This yellow-spotted millipede is one of the many creatures chomping on the forest litter.

There is so much chomping and munching and digesting and defecating going on in the forest’s old woody debris that if we could hear it, we’d run for our lives! The amount of cleanup done by nature’s housekeeping crew is so significant that if all that activity wasn’t going on, we’d be standing in a gigantic rubble pile. Furthermore, the dead wood would not be turned into nutrients for future generations of trees and other plant life.

As it decays over the decades, and perhaps centuries, dead wood acts as sponges for water, soaking it up in the wet season and offering it up to the creatures who need it during the dry season.

Logs like this play many roles in the forest.

but what about stumps?

Our Salish Sea lowlands, once covered by ancient Douglas fir forests, have been tree farms for the last century or two. So the dead wood normally in unharvested forests is largely missing. The ecosystem functions that would be performed by fallen trees are entrusted mainly to the big stumps that you may see scattered throughout the forest.

Stumps provide many of the same services as fallen trees, including a home for various kinds of invertebrates and small mammals.

Stumps provide many of the same services as fallen trees, including a home for various kinds of invertebrates and small mammals.

Sometimes it’s possible to tell what kind of a tree the stump used to be. The bark is a big clue if it is present, but on many old stumps the bark is no longer there. Two common kinds of stumps seen in the Salish Sea lowlands are Douglas fir and western red cedar. Sometimes the shape is a give-away. Douglas fir trees tend to have very round stumps, while the cedar trees are often lobed at the base, leaving behind lobed stumps. Cedar stumps are sometimes more common, not because they were a more common tree, but because of its wood’s natural resistance to decay.

the origin of stumps

Stumps are the remains of trees that may have been as old as 1,000 years when cut down. The stumps, which are also subject to the same decomposing processes mentioned above, may take up to 200 years to disappear.

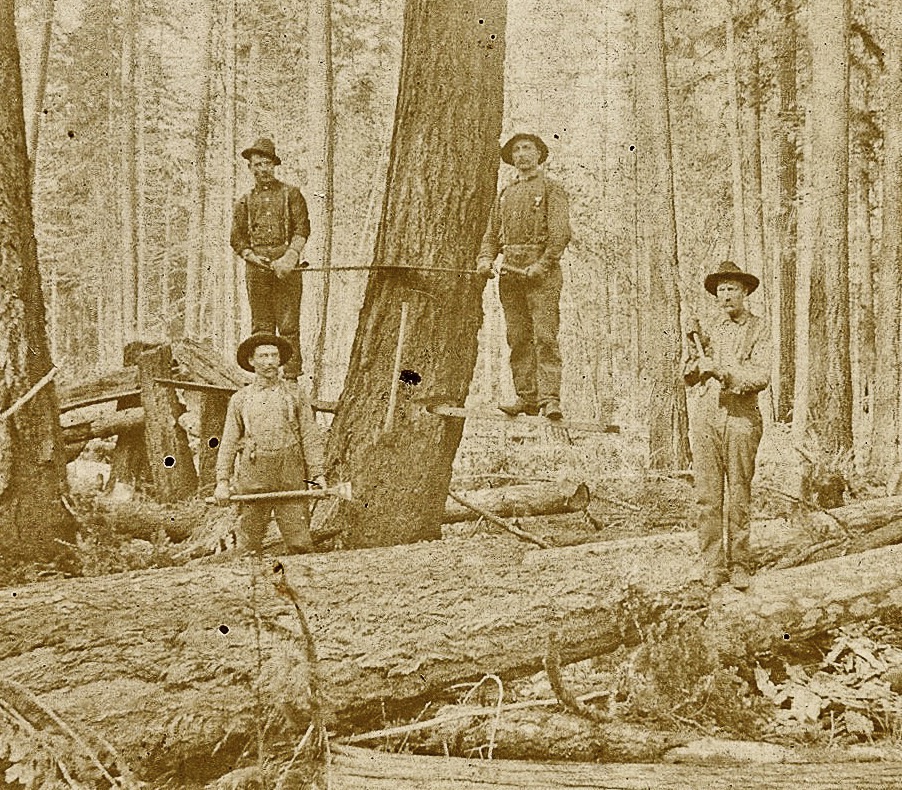

Loggers in this photo are posing with various tools that they used to fell trees. Two holding a crosscut saw are standing on springboards which were metal-tipped planks inserted into notches chopped into the tree trunks. Springboards served as platforms on which the fellers stood, allowing them to work above the dense undergrowth and above the wide lower parts of the old-growth trees, which were often full of pitch and rotten wood.

So because the loggers were cutting the trees well above the forest floor, sizable stumps were left behind.

Fellers standing on springboards highlighted in red. photo courtesy of Poulsbo Historical Society

The stumps shown in the gallery here are decaying, but one can still see the springboard notches, which are dark horizontal lines. One photo shows an actual springboard, with its steel tip that fit into the notch. (Springboard courtesy of Mark Schorn.)

These stumps illustrate just how large some of the trees were in this area. The distribution of the stumps also shows that not all of the trees were huge, but there was a wide variety of sizes, and the huge ones were a minority, even before logging began.

Forest of Giants by Scotti Wilson — www.scottiwilsonart.com

nurse stumps

As they decay, the tops of the stumps are also moist, fertile ground for seedlings that eventually grow into substantial shrubs or trees. These stumps that provide nourishment are sometimes called “nurse stumps.”

Western hemlock is one of the most common trees that grow on nurse stumps or nurse logs.

Sometimes a tree can be seen with its roots still shaped by the stump that nursed it in its youth, even though that stump has largely rotted away.

Old logs found in some forests sometimes also play a similar role, and they’re called “nurse logs.”

Nurse log examples can be seen in the Nurse Log article in this issue.

Nurse log examples can be seen in the Nurse Log article in this issue.

Here’s a tree that grew atop a tall stump, eventually sending its roots into the ground. As the stump rotted away, the tree tipped, but continued growing. What the camera couldn’t capture is that the trunk, to the upper right beyond the photograph, curves upward and eventually goes vertical again.

”Field Guide to Old-Growth Forests” by Larry Eifert is a really excellent overview of old-growth forests and their inhabitants, and it also points out where some might be seen in the Pacific Northwest.

stumps, people, and culture

This stump is an informal community art project. It is decorated differently each time I see it.

This stump is being used as an entrance to a home.

Besides the various other creatures that use the stumps, humans have also found uses for stumps. Sometimes large enough stumps have provided living space. This stump is at Guillemot Cove Nature Preserve in Kitsap County.

Another role stumps sometimes play is as a vehicle for artistic expression. This carved stump is at the Chico Salmon Park.

On a larger scale, the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe is building a stumps garden at Heronswood.

The garden is named x̣ə́w̕əs shəyí, which in the S’Klallam language means New Life.

The garden is still under construction, and it is intended to be reminiscent of an abandoned logging site. This is particularly relevant because the Port Gamble S’Klallam used to paddle from their homes to logging jobs across Gamble Bay. That will be memorialized by the remnants of a tribal canoe on the shore of a pond near the garden.

John van den Meerendonk has been the principle designer of the project, assisted in the overall concept by Daniel Hinkley. John has given an enormous number of hours on a volunteer basis and deserves a huge amount of credit. The stumps for the project were all donated by Denise Harris of Bainbridge Island and Pope Resources of Port Gamble/Poulsbo.

Christina Doherty loves to share her passion for getting outdoors and learning what lives and grows there. She has been a naturalist and outdoor educator for over 15 years, and has worn many hats: zookeeper, wildlife rehabilitator, kayak guide, and shell and shark-tooth beachcomber in the southeast (on a beach, she rarely makes eye contact). Part scientist, and part performance artist, she can usually be found turning over a log in pursuit of a salamander, mingling with mycelium and sharing more than you ever wanted to know about moss reproduction. Education: B.S. Zoology, State University of New York at Oswego, Master Birder, Certified Beach Naturalist, and Certified Interpretive Guide

John F. Williams, publisher of Salish Magazine: over decades of exploring underwater and in our forests and beaches, my experiences have been enriched by the insights of knowledgeable people. What I learned from them dramatically changed the way I see things,

I shared those insights by making educational films and through lecture tours. Now, I’ve created Salish Magazine to extend that notion of sharing insights by offering a wealth of articles that are keyed to the observable, but pull back the curtains to reveal the invisible.

Table of Contents, Issue #2, Winter 2018

Forest Stages

Photo Essay by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedPhoto Essay By John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedwhy does the forest occasionally change character as you travel...

Why Thin

by Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedhave you noticed how the forest changes as you follow the...

Rings

Musings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedMusings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedTree rings can be counted when a recently cut tree is encountered in...

Who Cooks

by Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedphoto by Nancy Seftonphoto by Nancy SeftonBy Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noteda family of barred owls flew into my neighborhoodI...

Nurse Log

by Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 photo by John F. WilliamsBy Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 above photo by John F. WilliamsFallen trees and decaying stumps lie on the forest floor in the midst of their thriving offspring. Much like beloved elders gone before, the trees on...

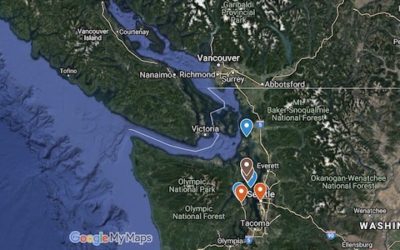

Map-2

Winter 2018Winter 2018The button below will open a Google map with some markers to show the locations of landmarks related to topics discussed in this issue #2 of Salish Magazine. For example, you can find some parks where you can see big, old stumps or different...