HOW OLD IS (WAS) A TREE?

Musings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

HOW OLD IS (WAS) A TREE?

Musings by John F. Williams, Winter 2018

Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noted

Tree rings can be counted when a recently cut tree is encountered in the forest. Trees may have been cut for harvest or thinning, or when a fallen tree is blocking a trail.

The most obvious reason for us informal explorers to look at the rings is to get a sense of how old the trees are in that neck of the woods. Like people, the age of a tree cannot be judged simply by its size — there are too many variables. But generally, each ring (a light/dark pair) will represent one year of growth. The lighter, wider part is from the rapid warm season growth, and the dark, thinner part is from the winter.

Why would you want to know the age of a tree? Personally, I just can’t help myself. I count rings from some deep-seated curiosity, the way young kids eagerly explore what’s around the next bend in the trail. Maybe I just never grew up.

Generally, counting the rings of a recently cut tree is a good way to estimate the tree’s age. In some cases, they are easy to count. This tree, for example, was cut when it was 20-ish.

But the age of the trees also holds clues to the history of the forest and what stage of growth it’s in. That, in turn, is a clue to what kinds of other living things one might find in that forest. For example, if the forest is 30 or 40 years old and a fairly uniform stand of Douglas fir, it’s unlikely that a visitor will see eagles or hawks hanging out there. But you might see a barred owl. It’s also unlikely that one will find huckleberries and salal, or much of anything else alive between the trees. Note that a foot is a good way to establish the size of the log.

See the Forest Stages article in this issue for more about different ages and stages.

See the Forest Stages article in this issue for more about different ages and stages.

But if you count 80 or more rings on a recently cut tree that seems typical in that area, you’re probably also seeing various kinds of fallen, rotting wood on the ground — rotting wood that is home to a cornucopia of small animals and other life. You’ll also likely see some variation in the sizes and species of trees, and an abundance of other plants growing between the trees. If, however, you find a stand of trees 100+ years old that are also very uniform looking, then Dorothy, you’re not in the middle of the bell curve any more — you have a mystery on your hands.

Visible rings on a stack of recently cut logs waiting to be loaded onto a truck.

young forest stage

For example, I was on a tour of the Illahee Forest Preserve (Kitsap County, Washington), and the guide pointed out a tree that was over 500 years old. However, the tree was only about 6 inches in diameter, and its neighbors were bigger, but not even 50 years old. How did they know how old the tree was without cutting it down?

An auger-like corer can be screwed into the trunk of a tree to remove just a small core sample from the tree. Then the rings can be counted in this core. In the case of the small, old tree, the rings were so close together that a microscope was needed to count them.

The stand of trees in Illahee Forest Preserve near a skinny 500 year old tree.

The image above is not from the 500+ year old tree, but it is quite a bit older than the average trees found in our post-harvest lowland forests — but it’s not considered ancient.

A third way to gauge the age of trees is to find a planning document for the forest you are in. The map below came from such a planning document and shows the ages of different stands of trees in 2015, when the map was made.

But that’s just a rough guide because in some of those stands I’ve seen recently cut trees that were considerably older than the age assigned to the stand.

from “Forest Stewardship Plan for the Ecological Restoration of Port Gamble Forest Heritage Park”, June 1, 2016

a challenging puzzle

I said that recently cut trees often offer easy rings to count, but sometimes you might discover other opportunities. The log in the photo below was found on a beach (Fort Ward Park, Bainbridge Island). It was tossed around as driftwood long enough that the soft parts of the tree rings were worn away, but the harder parts remained. That makes the rings easy to count, except for the fact that there are so many of them.

Below is an overview photo that extends from the center to the right edge of the end of the log. Below that are three detailed photos of that overview. If you like puzzles, try to come up with a ballpark figure for how old this tree was when it was cut (or broken)? It’s a challenging puzzle.

Here is the above photo divided up into 3 pieces to make it easier to count the rings. Use the unique dark shapes to figure out where each detail photo belongs in the overview above.

audience participation

There’s not the time or space in this article to tell the stories of all of the possible ring variations, but we’ll address some of these in future issues. In the meantime, keep your eyes peeled for extra-ordinary tree rings. If you see something remarkable, snap a photo and post it on Instagram with the #salishmag2 hashtag (Salish Magazine Issue #2). That’ll help give us fuel for future articles.

John F. Williams, publisher of Salish Magazine: over decades of exploring underwater and in our forests and beaches, my experiences have been enriched by the insights of knowledgeable people. What I learned from them dramatically changed the way I see things,

I shared those insights by making educational films and through lecture tours. Now, I’ve created Salish Magazine to extend that notion of sharing insights by offering a wealth of articles that are keyed to the observable, but pull back the curtains to reveal the invisible.

Table of Contents, Issue #2, Winter 2018

Forest Stages

Photo Essay by John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedPhoto Essay By John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedwhy does the forest occasionally change character as you travel...

Why Thin

by Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Arno Bergstrom, Nancy Sefton, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedhave you noticed how the forest changes as you follow the...

Stump Stories

Photo Essay by Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy Christina Doherty & John F. Williams, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedtrees dieMaybe they die...

Who Cooks

by Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedphoto by Nancy Seftonphoto by Nancy SeftonBy Leigh Calvez, Winter 2018 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where noteda family of barred owls flew into my neighborhoodI...

Nurse Log

by Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 photo by John F. WilliamsBy Sharon Pegany, Winter 2018 above photo by John F. WilliamsFallen trees and decaying stumps lie on the forest floor in the midst of their thriving offspring. Much like beloved elders gone before, the trees on...

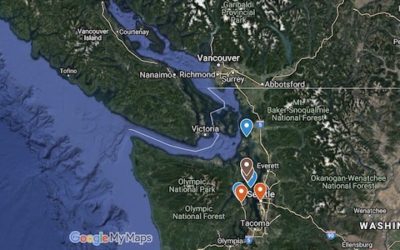

Map-2

Winter 2018Winter 2018The button below will open a Google map with some markers to show the locations of landmarks related to topics discussed in this issue #2 of Salish Magazine. For example, you can find some parks where you can see big, old stumps or different...