HOME SWEET HOME, LIMPET STYLE

by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021

Photos by Barbara Erickson

except as noted

HOME SWEET HOME, LIMPET STYLE

by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021

Photos by Barbara Erickson except as noted

WHOOPEE! With the approach of summer and loosening of COVID restrictions, it’s time to head out exploring! For me, that often means going to a nearby rocky beach to see what I can find. If you venture to carefully examine the rocks, true treasures may be found. Animals that form a shell of some kind often blend into the surrounding rock and may be easy to overlook. One such creature is the limpet.

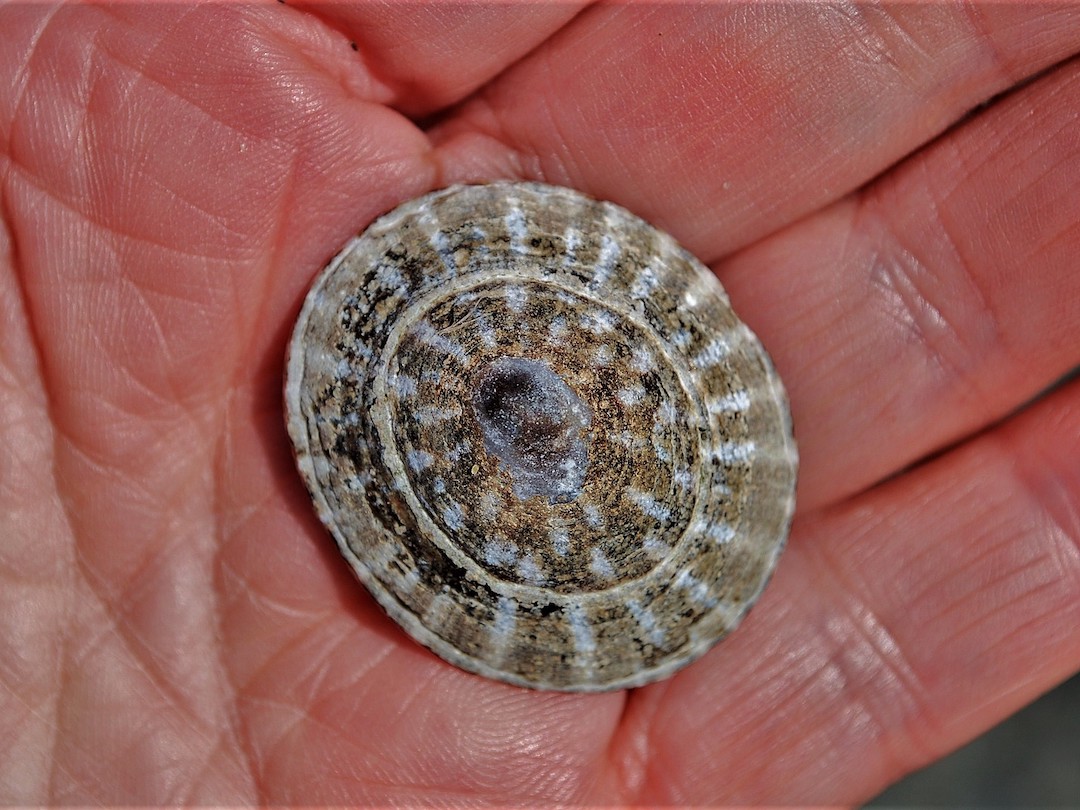

Mollusk relatives of snails, limpets are distinct with their flattened, cone-shaped shells. Latching onto solid surfaces with their single, suction cup-like foot, limpets are small, usually one-eighth to two and a half inches across. Although their shell grants them survival in many ways, you are likely to find their empty shells lying among the beach rubble. With time and waves, the top of a limpet shell can become worn away to the point where all that is left is a smooth ring of shell, making it difficult to identify. Eventually, all the minerals and other elements composing the shells are returned to the ocean, where they become available for other living things to use. Nature wastes nothing.

Like other shoreline invertebrates, limpets do not begin life with a shell, but as tiny, juvenile, microscopic bits of zooplankton. These tiny bits of life are free-floating in the open ocean, feeding on bits of algae and likewise being preyed upon by larger zooplankton. After a certain amount of time, varying with the species, the survivors feel the urge to settle down to the bottom, attach to a solid surface, and form a tiny shell using calcium and other minerals found in the sea water.

Follow this link to see another short time lapse of limpet motion as well as some of their other low-tide neighbors in this Virtual Exploration.

Follow this link to see another short time lapse of limpet motion as well as some of their other low-tide neighbors in this Virtual Exploration.

Because they are vegetarians, limpets must make their way to the shoreline, where most of their food lies within easy reach. They accomplish this by gliding along on their single, mucus-covered, muscular foot, like that of a snail. When they find a suitable location full of algae-covered rocks, they set up permanent residence. Although they cannot leave their shells since they are permanently attached to them, limpets move about while carrying their shells overhead. They move constantly in search of greener pastures of nutritious algae, which they scrape off the rock with their rough, tooth-covered tongues.

Recent research has shown the strength of the average limpet tooth is five times greater than most spider silk and stronger than man-made materials such as Kevlar fibers — almost as good as the best high-performance carbon fiber materials. This discovery might help improve future composites used to build aircraft, cars, boats, and dental fillings.

Establishing their own territories, limpets mow down a path of their preferred meal. Other vegetation moves in to replace that and, if the new growth is not to the limpet’s liking, it uses the front of its sturdy shell to bulldoze the growth away, repeating this as often as necessary until its preferred crop returns. In this way they “garden,” fertilizing their crop with their own droppings.

While limpets cruise around in search of food, many often have a favorite parking place where they regularly return to rest. With time, and the wearing away of the rock around the rim at the bottom of their hard shells, circular scars are formed in the rock at these places. Called “home scars,” these round indentations are dead giveaways as to limpets’ preferred resting spots, although only the most observant eyes will detect them.

A limpet’s life is full of threats. Other limpets may invade their territory, threatening their food supply. To counteract this, the defending limpet will approach the invader and wedge the front edge of its shell under that of the intruder, pushing it away. The intruder may well push back, but the weaker of the two finally retreats. In this way individual territories are established, often side by side, with each limpet learning to respect the boundaries of the others. Limpets do tolerate others to some degree; their territories may overlap a bit and their resting spots may be close together.

Limpet predators include shore crabs, clingfish, shore birds (such as the oystercatcher), and the six-rayed, purple/ochre, mottled, and sunflower sea stars. The shape and texture of the shell matters. The flatter and smoother the shell, the less secure hold a predator can gain. Without ears or true eyes, limpets may be thought to be at a disadvantage when it comes to being alert to danger. Far from it: Their two small eyespots, at the base of their anterior tentacles, can detect dark and light, so they are aware of shadows passing over them. Limpets can detect vibrations and are chemically sensitive. Research has shown that when threatened by a sea star, a limpet will beat a swift retreat (swift, by limpet standards, that is) if a tube foot from said star touches its sensitive foot. They also can chemically sense the near presence of such predators, moving away before actual contact. Sometimes they will face the threat head-on by using the edge of their shell as a battering ram against the larger aggressor.

When tides are low, limpets run the risk of drying out and cooking in their own shells. They have developed a special method for dealing with this threat. While they prefer a sheltered spot under a rock or in a crevice, they may sometimes end up on top of a rock, exposed to the elements. Since their mucous-covered foot cannot move across dry surfaces, in this case they are pretty much stuck there. Either way, they securely attach themselves to the rock and pull their foot muscles tight to create a strong suction that firmly seals the edge of their shell down. In this way, they create a secure, tight capsule to hold in water for breathing and cooling until the tide returns. Some limpets can exert as much as 40 pounds of pressure per square inch with this suction, and so this method also works well against predators that cannot pry them loose to get at their soft insides. Don’t try to remove a limpet from its rock; you will surely injure or kill it in the process!

Limpets gathered in the shade on a bluff.

Limpet shells — whether tall and pointed or squat and shield like, smooth and solid colored or radially ribbed and striped or mottled with neutral shades — suit their inhabitants well, as the inside is always glass-smooth against the limpet’s soft body. As limpets grow, they enlarge their shells both vertically and laterally. The shells blend in beautifully with their surroundings and often become covered with small barnacles or bits of seaweed.

While some of us might live nearby, very few of us live right on the beach. It is important for us to remember we are merely guests here and to act accordingly. After our exploring, we can return refreshed to our warm and dry homes, leaving the limpets and others safe to continue their simple, yet not-so-simple, lives among the rocks and seaweed just as they like it – cold and wet!

Born and raised in Montana, I developed a deep love, appreciation, and respect for the land and all its inhabitants. I am a life-long learner and educator. Now retired, I fill my days with nature studies, writing, photography, and volunteering with environmental programs. I’ve lived in Poulsbo for 40+ years with my husband of 55 years and a little mutt named Scruffy.

Here’s the link to my blog, Ladybug’s Lair:

Ladybug’s Lair (flyhometoladybugslair.blogspot.com)

FIND OUT MORE

Table of Contents, Issue #12, Summer 2021

Beach Wrack

by Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedby Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedOn a warm sunny day, the shores of Puget Sound are filled with the smell of rotting seaweed. Flies are heard before they are seen, swarming above...

Hermit Crabs

by Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensenby Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensen The waves fly onto the beach as if they were racing each other. Which one can...

Piling Up

by Jeff Adams, Summer 2021 photos by Jeff Adams except as noted fact checked by Andy Lambphoto by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Jeff Adams, Summer 2021 photos by Jeff Adams except as noted fact checked by Andy LambAs a marine ecologist and nature...

RVs of the Beach

by Tom Noland, Summer 2021 photos by Tom Noland except as noted fact-checked by Greg Jensenby Tom Noland, Summer 2021 photos by Tom Noland except as noted fact-checked by Greg JensenWalking the shore of Cama Beach State Park on one of the lowest tides in recent...

Shell Shapes

by Chris Rurik, Summer 2021photo by Sarah Cavanaughphoto by Sarah Cavanaughby Chris Rurik, Summer 2021 Photos by Sarah CavanaughI have a collection of broken shells. They litter my desk and drawers, wave-smoothed fragments of curves and spirals, half-bleached, like...

Moon Snails at Low Tide

by Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyBy Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyAt the end of May, we had two days of minus 3.8’ (minus 1.15 m) tides at the northern end of the Kitsap Peninsula; wonderful for...

A Rainbow of Crabs

by Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen photo by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen On a Saturday in early March, in an attempt to shake off the last of the winter lockdown slump, my partner...

Poetry-12

Summer 2021Photo by Jessica C. LevinePhoto by Jessica C. LevineSummer 2021To begin this section of poetry, here are three haikus which speak to our excessive heat this summer.by Drea Dangerton Cold water absentDrive belt for water massesFrayed, hardly churning...

Hello Under There

Proper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 photo by Kaylani Siplinphoto by Kaylani SiplinProper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 At first glance, the beaches along the Salish Sea may seem desolate, except for the...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.