CLAMS: The RVs of the Beach

by Tom Noland, Summer 2021

photos by Tom Noland except as noted

fact-checked by Greg Jensen

CLAMS: The RVs of the Beach

by Tom Noland, Summer 2021

photos by Tom Noland except as noted

fact-checked by Greg Jensen

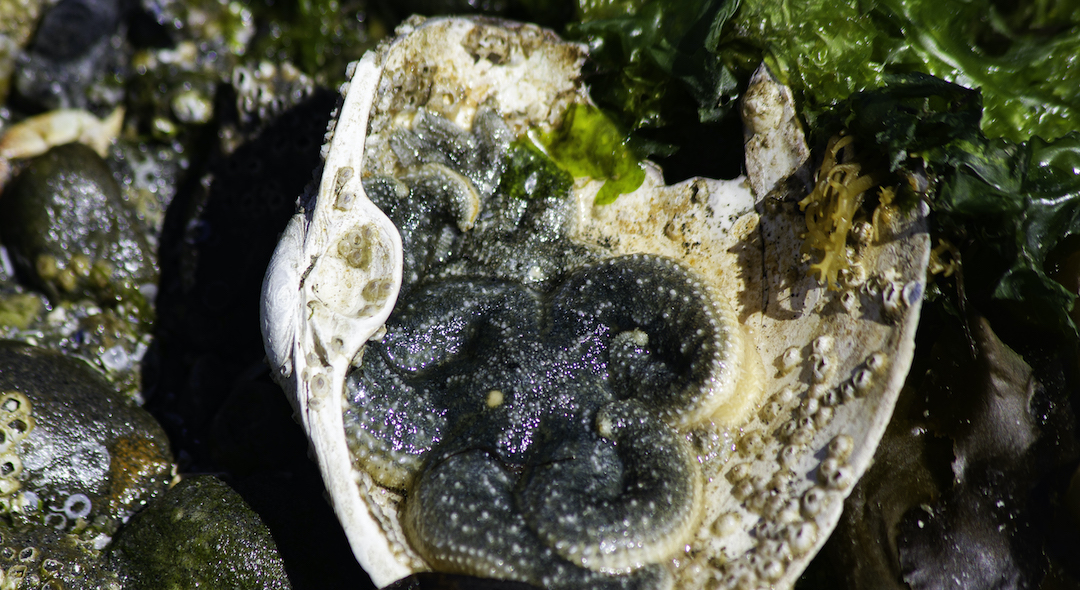

Walking the shore of Cama Beach State Park on one of the lowest tides in recent history, spurts of water eject onto my boots from mysterious holes in the sand. Clam shells are everywhere, strewn about by the receding tide. Large horse clam shells are covered with small barnacles; sea stars are curled up in some of the largest shells that still hold a bit of sea water. Some of the empty clam shells are ruffled on the outside; others are smooth and ridged.

Seeing all the empty clam shells on the beach made me wonder about the lives of clams around the Salish Sea.

Clams are in a group known as the bivalves (two shells). Within this group are clams, mussels, and oysters, as well as scallops. Most clams are mobile burrowers, whereas mussels and oysters are sessile (attached to a substrate). Scallops swim in the deep waters of the Salish Sea. Clams take their homes with them and are like a motorhome, fully self-contained and ready for the road, or in this case the beach.

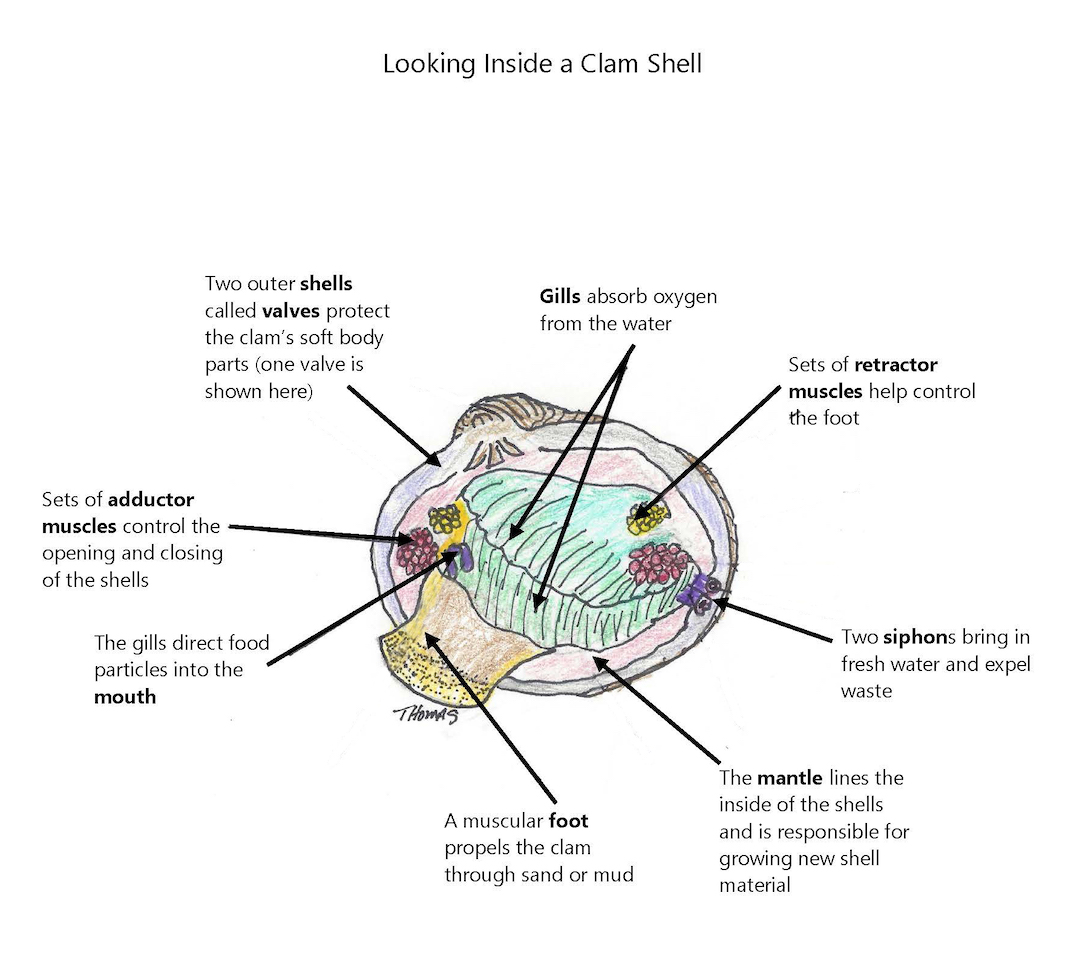

The outer armor of a clam’s RV home is its two shells, which are attached together by a hinge. The shells are lined inside with a membrane called the mantle. Inside the mantle are the clam’s organs (stomach, heart, gonads, etc.). Two parallel siphons can be extended out of the shells to bring in fresh water and expel waste. The clam’s muscular foot is used to dig, moving the clam through sand or mud. Other muscles close the shells when needed.

The clam’s foot is an amazing muscle. The clam can extend its foot outside the shells and fill the appendage with water, causing the foot to expand and creating a space in the sand that the clam can then move down into. This is known as fluidizing. By loosening up the sand, the clam’s foot reduces friction on the clam, allowing it to drag its shell downward. This video shows how it’s done by a razor clam: Facebook page

Clams feed largely on organic matter they filter from the water. They can extend their siphons to the surface of the sand or mud, creating the small holes we often see at the beach. When the tide is in, the clam’s incoming siphon brings in food-rich water through their gills, which are covered with mucus and cilia (microscopic hairs). The cilia sweep food particles (plankton and other organic matter) into the clam’s mouth. The clam also obtains oxygen from the water, similar to how a fish breathes. After incoming water has passed through the gills and had the oxygen and food particles removed, the water is pumped back into the ocean through the outgoing siphon.

After they have provided food for other creatures, and their empty shells litter the shoreline, clams continue to benefit the ecosystem. When the tide goes out, empty clam shells provide pools of water for small sea stars, barnacles, and other creatures to stay in for protection. Clam shells are attachment places for barnacles and seaweeds. As the shells are broken up on the beach, they add calcium, minerals, and other nutrients back into the beach ecosystem.

How does a clam build its shell? Clams grow by laying down a lattice of protein and covering it with calcium (think rebar and concrete). They get the calcium they need from the ocean around them. The mantle uses calcium and proteins to make a kind of gluey substance that forms a ring around the edge of the mantle that hardens as the clam grows. Clams are like trees in that they produce rings in their shells as they grow. Like tree rings, the rings of clams are closer together as their growth rate slows down. During the winter and fall, the rings of a clam are darker, perhaps due to cooler water temperatures, reduced food abundance, or spawning. In some species, such as the cockles, counting the annual rings is easy, but for some species counting them accurately involves looking at a cross-section under a microscope.

photo by John F. Williams

photo by John F. Williams

Clams have long been a delicacy for humans, sea otters, birds, and other creatures. Otters use rocks to break open clams on their stomachs as they float in the ocean. Gulls and other birds will pick up clams and drop them on rocks from the sky high above the beach, breaking them open and eating the insides. Sea stars eat clams by prying them open with their arms and then inverting their stomachs into the open shells to digest the clam. Moon snails eat clams by drilling holes into the shells to access the flesh. In places like Alaska, bears have been known to dig up clams on the beach.

clams of the Salish Sea

Now that you know some bivalve basics, let’s meet the different species that live in the Salish Sea region and some fascinating species from beyond.

Up to 15,000 different types of clams are found around the world. Here in Puget Sound, the following types are common and some are harvested for food.

geoduck

You’re unlikely to find a geoduck during a casual beach walk, but you can’t talk about Puget Sound clams without knowing about the “boss clam.” In the Salish Sea region, the geoduck (it’s pronounced GOOEY-duck) is the largest burrowing clam. Averaging around 1.5 pounds but known to weigh up to 10 pounds, their shells can be up to 10 inches in length and the siphons or necks can reach over 3 feet long. They are one of the longest living clams, averaging over 140 years. During this lifespan, females can produce up to 5 billion eggs. They are broadcast spawners, sending out sperm and eggs in mass. They live in deeper water and burrow down to 3 feet in the sand. Here’s an article about geoduck history, harvest, and farming:

manila clam

Up to 2.5 inches in length, Manila clams have an oblong shell with concentric rings with radiating ridge lines. Shells are generally gray, brown, or mottled in color, often with purple on the inside. They burrow in sand, gravel, or mud at a depth of 2 to 4 inches, above the half tide level. This species is native to Japan and was accidentally introduced to Canada during the 1920s or 1930s. Here’s a link from the Canadian government about Manila clams:

native littleneck clam

Around 3.5 inches in size, littlenecks also have concentric shell rings. Shell colors are typically white or gray mottled with brown, and the insides of their shells are white. They burrow in sand, gravel, and mud at depths of around 6 to 10 inches, from the mid intertidal zone down to 60 feet.

butter clam

Butter clams are heavy and large (shells up to 5 inches) and are oval to square in shape. Their shells have concentric rings but no radiating ridges and are yellow to gray to white in color. They are found on sand, gravel, and cobble beaches at a depth of 12 to 18 inches in the lower intertidal and subtidal zones.

varnish clam

The varnish clam’s shell is up to 3 inches long, oval in shape, and somewhat flat. These clams have concentric rings on their shells with a shiny brown coating on the outside and purple coloration on the inside. They can be found in the upper third of the intertidal zone, higher on the beach than any of our other clams, and sometimes as deep as the lower tidal zones. They dig into a shallow depth of 1 to 2 inches. These clams are most abundant near freshwater runoff on sand, cobble, mud, or gravel beaches. This species is native to Asia and probably arrived here in ship ballast water in the 1990s.

The Savory Varnish Clam – Sound Water Stewards

cockle

Cockles can grow up to 5 inches long and are rather beefy clams with a rounded triangular shape. The shells are mottled and light brown in color, with quite pronounced, evenly spaced ridges that fan out from a pointed hinge. They live shallowly in sand and mud at a depth of 1 to 2 inches in the intertidal and subtidal zones.

macoma

The Macoma clam is up to 4 inches long, oval to square in shape with very thin, chalky white shells with upturned ends at the siphon exit. They live in mud and sand in the intertidal zone at depth of 4 to 6 inches.

horse clam

Horse clams are one of the larger clams here in Washington, also known as gapers. They can grow to 8 inches in size, weighing up to four pounds, and are oval in shape. They have chalky white shells with patches of brown skin like dried shellac. They live deep (1 to 2 feet) in the mud and gravel at the lower intertidal zone. The name “gaper” comes from the fact their shells don’t completely close around their siphons, leaving gaps.

ODFW About Gaper Clams (state.or.us)

eastern softshell clam

Eastern softshell clams can be 6 inches long, with a squarish or oval, brittle shell that has thin yellow or brown skin around the edges. Like horse clams, they can’t completely pull their siphon into the shells. These clams like low salinity and are found in the sand and mud near the mouth of rivers at the upper half of the tidal zone. These clams are deep diggers as well, being found at a depth of 8 to 18 inches. It appears this species inhabited the Pacific Coast in prehistoric times but went extinct here before human habitation, based on archaeological evidence. It was accidentally introduced to San Francisco Bay in shipments of Atlantic oysters in the late 1880s and is now widespread on the West Coast.

Mya arenaria | The Exotics Guide

razor clam

This species is found along sandy beaches of the outer Washington coast. These clams look like the old-fashioned straight-edge razors of yore that are folded closed. They are up to six inches long with thin brown shells. Their siphons are too large to pull into their shells. They are able to quickly dig down into the sand to escape predators (or human clam diggers).

more Salish Sea bivalves

mussels

Salish Sea mussels are typically three to six inches in length and include the smaller blue mussel and the larger California mussel. Shells are black and brown. Mussels grow in large clusters in the intertidal zone, attaching to rocks, pilings, and other hard structures. They attach themselves with very strong, brown threads called byssus or “sea silk.”

oysters

Oysters can be up to 12 inches in length. They have chalky white shells that are irregular in shape with wavey, sharp edges. They are found growing together on rocky beaches in the intertidal zone. It is important not to remove oyster shells because their spat (baby oysters) attach to shells where they grow. Several types of non-native oysters are farmed in the Salish Sea region. Efforts are underway to restore populations of the native Olympia oyster. This article provides an overview of oyster history in our region:

The Pacific Shellfish Institute | Washington (pacshell.org)

scallops

People harvest four types of scallops locally: pink, spiny, weathervane, and rock. They live in deep waters and are usually hand harvested by divers. The first three species can swim to get away from predators, while adult rock scallops attach themselves to rocks. The singing pink scallop is so named because of the way they clap their shells open and closed when moving, making them appear to sing. Scallops have fascinating adaptations, such as chemoreceptors and bright blue eyes around the edges of the mantle.

The spiny pink scallop is ready for sweater weather – Washington State Department of Ecology

bivalves in fresh water?

Clams and mussels also inhabit some freshwater ponds and streams in the Puget Sound area. Because they are quite sensitive to water pollution and can live up to 50 years, freshwater mussels can tell us about the health of a stream system. For more information see:

15-060_01_Mussel_Outreach_July_20_2015_Final_low_res.pdf (xerces.org)

Fingernail clams are found in some freshwater ponds and streams. Their shells are usually a quarter-inch long or smaller and translucent like a fingernail. I’ve come across them in Snohomish County ponds such as those at Narbeck park in Everett. They are an important food source for juvenile fish.

record book of bivalves

One of the oldest living clams ever found was an Artica islandica estimated at 507 years old. This clam was found in 2007 off the coast of Iceland. People named it “Ming” after the dynasty that was ruling China at the time this clam was born.

The largest clam in the world? Not our geoduck by a long shot. The tropical Tridacna gigas can weigh over 600 pounds and span 4 feet across. These clams do not eat or trap divers as legends would have it; they close their shells so slowly a diver can easily pull away. This giant survives using a symbiotic relationship with algae that grow in their mantle, producing sugars and proteins that help these clams grow to enormous size. Because of this relationship with photosynthetic algae, the giants are found in shallow waters where sunlight reaches the seabed.

editor’s note

The focus of this article is on observing and enjoying clams and other bivalves in their environment. Harvesting these creatures for consumption requires a knowledge of licensing requirements, beach closures, and shellfish toxins. We leave those topics to the experts and regulators, such as the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Washington Department of Health. See these web pages:

Shellfish Beach Closures :: Washington State Department of Health

Shellfishing regulations | Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife

For convenient clam ID guide, the State Department of Health provides these links:

Bivalve Shellfish Identification Handout (wa.gov)

For more details about native shellfish in Puget Sound, see:

Thomas Noland is a naturalist and photographer living in Everett. In addition to his interests in paleobiology, he is a dedicated entomologist and caretaker of numerous rescued cats.

.

Table of Contents, Issue #12, Summer 2021

Beach Wrack

by Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedby Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedOn a warm sunny day, the shores of Puget Sound are filled with the smell of rotting seaweed. Flies are heard before they are seen, swarming above...

Hermit Crabs

by Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensenby Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensen The waves fly onto the beach as if they were racing each other. Which one can...

Piling Up

by Jeff Adams, Summer 2021 photos by Jeff Adams except as noted fact checked by Andy Lambphoto by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Jeff Adams, Summer 2021 photos by Jeff Adams except as noted fact checked by Andy LambAs a marine ecologist and nature...

Shell Shapes

by Chris Rurik, Summer 2021photo by Sarah Cavanaughphoto by Sarah Cavanaughby Chris Rurik, Summer 2021 Photos by Sarah CavanaughI have a collection of broken shells. They litter my desk and drawers, wave-smoothed fragments of curves and spirals, half-bleached, like...

Moon Snails at Low Tide

by Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyBy Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyAt the end of May, we had two days of minus 3.8’ (minus 1.15 m) tides at the northern end of the Kitsap Peninsula; wonderful for...

A Rainbow of Crabs

by Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen photo by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen On a Saturday in early March, in an attempt to shake off the last of the winter lockdown slump, my partner...

Poetry-12

Summer 2021Photo by Jessica C. LevinePhoto by Jessica C. LevineSummer 2021To begin this section of poetry, here are three haikus which speak to our excessive heat this summer.by Drea Dangerton Cold water absentDrive belt for water massesFrayed, hardly churning...

Hello Under There

Proper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 photo by Kaylani Siplinphoto by Kaylani SiplinProper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 At first glance, the beaches along the Salish Sea may seem desolate, except for the...

Home Sweet Home

by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021 Photos by Barbara Erickson except as noted by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021 Photos by Barbara Erickson except as notedWHOOPEE! With the approach of summer and loosening of COVID restrictions, it’s time to head out exploring! For me,...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.