SHELL SHAPES

by Chris Rurik, Summer 2021

photo by Sarah Cavanaugh

photo by Sarah Cavanaugh

SHELL SHAPES

by Chris Rurik, Summer 2021

Photos by Sarah Cavanaugh

I have a collection of broken shells. They litter my desk and drawers, wave-smoothed fragments of curves and spirals, half-bleached, like castoff pendants. On the beach it’s not the perfect specimens that draw me, though perhaps they should. It’s the sculpted forms, no two alike, of shells being returned to sand: nature’s attempt at order being ground back down.

photos by John F. Williams

Here on the shores of Carr Inlet, in the shallow southern reaches of the Salish Sea, rock cobble beaches give way to extensive mudflats. There is no vertical relief, no pockets of habitat like those found in rocky reefs, no pre-made shelter. Even I feel naked on the mudflats. If an animal doesn’t know how to dig or build a shell, it has no place to hide.

I like to walk with the tide as it rises. At its lowest edge, waves murmur over thin patches of eelgrass that have regrown since the days of destructive geoduck harvest. I find in firm sand the drill holes of tube worms. Here and there are the lumpy tips of geoduck siphons. Were I to dig, I would find a rich assortment of thin-shelled clams, polychaete worms, the occasional heart cockle. In these strata of packed sand, empty shells are rare. They’ve been taken elsewhere, upward.

photos by John F. Williams

The tide steals up on you fast on the flats. To stay ahead of it I scramble across fields of beige and white sand dollar shells. They fragment like so many cookies underfoot. Beneath them, just under the sand’s surface, are the living purple sand dollars, thousands and thousands of them.

Here and there I see a large old horse clam shell painted with algae and barnacles. At the line where mud gives way to rock, barnacles cover every surface. I find limpets and chitons. Pacific oysters laze about. I follow the curve of the beach into a protected cove, where Manila clams and varnish clams lie in half-buried beds. Mussels cover pilings. Shore crabs and brittle stars slip through the terrain like cross stitch needles, and periwinkles and turban snails climb with me in the shallows.

From a distance, the beach’s geometry is simple. It does not suggest that it could support a diversity of lifestyles. But there sure are a lot of different shelled creatures here.

My own shell, at the moment, is an interesting one. It sits on a bluff above the beach. Built decades ago by an interior designer and his musician wife, in the shape of a cross, it sits aslant to the shoreline, oriented neither to sun nor sea but The Mountain itself to the southeast. My uncle told me the house once held a pipe organ. When he walked the beach at night, he would hear rich music rolling off the bluff, mixing with the killdeer’s cries.

The house had not been lived in for several years when my wife and I moved in. Rhododendrons loomed like trees. Alders blocked the view. It took time to banish a stale smell we could not identify, something like sun-bleached old clothing.

We were renting the place. Before long we were hoping we might buy it. The house responded to our breath of life. From my writing desk in the corner of the living room, surrounded by concentric scatterings of books, notes, collected shells and bones, toys, plants, paintings, and, beyond the tall windows, wave patterns, cloud patterns, and shorelines, it felt as though I were in the center of the world.

But that hope was not meant to be. The house is not for sale. Nor will it be. And we have come to understand that it is undermined anyway by its singular focus on the distant peak. Not only is it built too close to the edge of the bluff, it sits atop a seasonal creek. Already there have been nearby landslides. In the words of a hired coastal engineer, the house’s precarious perch needs not an investment in shoreline armoring but a long-term strategy of “mitigated retreat.”

Which I guess applies less to the house than to its occupants.

The transition of cobble to sand to driftwood to seagrass is seen on many beaches in the Salish Sea region. photo by John F. Williams

Rising inch by inch, hour by hour, the tide takes me up the cobble beach. Just before I reach driftwood and beach grass, the rocks give way to sand that is as raw as sugar, ready to blow away on a good wind. Here is where waves leave anything light or thin. I pick through beds of empty shells. Manila clam shells, whole and broken, stand out as faded purple swatches. A red rock crab claw vibrates with sand fleas. The pristine white flecks of storm-beaten shell fragments could be mistaken for pebbles.

For all the diversity of shell types here, one species dominates my collection. It’s an oddball, hard to find but hard to miss, a shell that becomes more beautiful when broken: Lewis’s moon snail.

Our moon snail is large. Its shell, the size of a softball, is remarkably spherical, moonlike, and in death it even grows gray and pitted like the moon. Inside the whorls, where the fleshy animal lived, the shell’s surface is stunningly lacquered in orange and fawn with a patina so smooth it feels soft. It can only be seen when the shell is broken.

And the shell, being a spiraled chamber rather than a hollow sphere, fragments into infinitely interesting shapes. I have one in my collection that looks like a half-bloomed rose. Another reminds me of a tulip.

photo by Sarah Cavanaugh

The body of a living moon snail can expand to nearly encompass its shell. It can contract into the shell and shut behind itself a horn-colored door. Living underwater, a moon snail’s preferred mode of transit is to spread its body flat around its shell like the white under an egg yolk and then, like a sneaky submarine, sink a few inches beneath the silt bottom and use an outpouring of mucus to grease its way. It’s the rare snail that gets around well in sand and mud, which affords it access to its favorite food, clams. When it finds a clam, its elephant-skinned foot folds around it. Over a few days it drills a hole in the clam’s shell, liquifies the clam’s body with enzymes, and sucks out a meal of fresh chowder. It’s a clinical way of killing. The drill holes are countersunk, as perfect as a furniture-maker’s when I find the empty clam shells at the high tide line.

A live moon snail. photo by John F. Williams

A clam shell sporting limpets and a countersunk hole likely made by a moon snail. photo by John F. Williams

See also Moon Snails at Low Tide in this issue.

See also Moon Snails at Low Tide in this issue.

Back when computers filled rooms and could be rented for half-a-million-a-month in today’s dollars, and their precious power was enlisted to help with some of the world’s most fundamental questions, like the mathematics of moon landings, a paleontologist named David Raup saw their potential to shine a light on nature’s underlying design. He used an IBM 7090 to predict shell shapes.

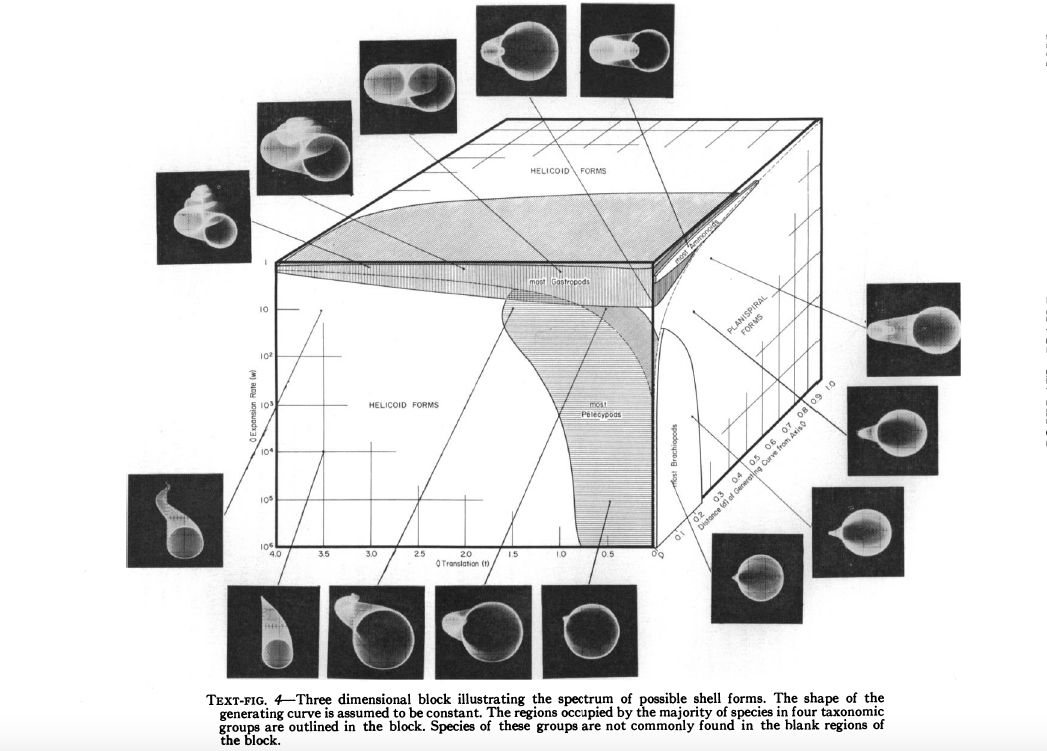

Earlier naturalists and mathematicians had recognized that shells, especially the coiled shells of snails, grow according to fixed parameters in a logarithmic spiral. Raup, refining the idea, found that only four parameters are needed to create the world’s great diversity of shell forms: shape of the generating curve, rate of the curve’s expansion, amount of overlap between successive whorls, and distance of each whorl from the axis of coiling. By tweaking the parameters, he could approximate any spiral shell in the world — and create many that have never existed.

photos by John F. Williams

Raup used the computer to understand the full range of what is mathematically possible. Then, working backward to what has actually existed, he tried to get a sense of how different groups of shelled creatures, snails and clams and ammonites and others, have clustered in distinct general “morphospaces.” Then he could theorize about why.

Take the moon snail eating a clam. The shells might look quite different, but both can be generated by tweaking a few parameters. The moon snail’s spherical spiral represents a rounded generating curve that expands at a moderate rate, overlaps itself significantly, and does not stray far from its axis of coiling. The clam’s two shells, on the other hand, have a wide-mouthed generating curve that expands very quickly, allowing the two halves to meet within a single revolution. The bump at a clam’s hinge is the early part of the shell’s spiral.

Raup produced three-dimensional graphs to show that all clams, having similar basic shell parameters, occupy a sliver-like swath of the total mathematical possibilities. Snails occupy a wider swath, but a different one. Shell shapes are not random. They cluster into basic forms. And around them are great empty morphospaces.

For Raup, it raised the question: have these untried shell forms not existed because they are not viable as lifestyles, perhaps not structurally sound or ill-suited to real-world environments?

Or is it that life has not yet had the time to explore all possibilities?

Image from Digital Seashells and David Raup by Dr. M in Deep Sea News, July 16, 2016.

I think about the braided channels of history, of design and technology. Are the beach houses we know the only options? Are they thorough? Exhaustive?

Or are they the slivers of focus produced when one idea is followed to the next, and the next, and each assumption builds on the last until the path is so well-worn it’s hard to see any others, and the technologies require each other, and a body’s very design is built upon parameters that become assumptions?

It would be a lot easier to answer such questions if we could read history clearly.

For several years I volunteered at the old Burke Museum in Seattle. A few mornings a week I would pedal up the hill to the university, lock up my bike, and enter the dark brick building. Sweaty, I would take the dented staff elevator into the basement, where I helped to keep things organized in the invertebrate paleontology lab.

Metal cabinets filled the basement like library shelves. Each cabinet was packed with dozens of drawers, and each drawer held hundreds of fossils in cardboard trays. There were shells of every shape and hue, every mode of preservation, representing hundreds of millions of years of history. I got to hold pearly ammonites from Little Sucia Island and ancient dusty brachiopods from Germany. Every drawer held revelations. There were shell shapes that no longer exist; others that haven’t changed in eons. There were even a few small moon snail shells.

Reading the fossil record has been compared with browsing a library in which ninety percent of the books have been burned. The odds that a living thing will be preserved are miniscule. Shells, though, have long been recognized as one of the richer and more useful parts of the fossil record. After all, they are hard parts that live in the types of sedimentary environments that tend to preserve signs of life. They are diverse, consistent, and recognizable. Fossil shells are used to index time, calculate rates of evolution, understand mass extinction events, and gauge past water conditions.

Yet gaps are everywhere. And it’s not just the impossibility of finding orderly sequences of fossils in a vast crumbling world.

The collection managers asked me to go through every tray to ensure they held the correct fossils, with the correct labels and the proper padding. I was to make sure the collection was properly ordered by locality numbers and accession numbers.

As I began, I found myself wondering why such a collection would need several full-time managers plus volunteers like me — were these not objects that had lost the capacity to move? But it didn’t take long to see that discrepancies were everywhere. Pink slips of paper spoke of fossils that had been borrowed by researchers and never returned. Others had been returned to the wrong place. Some fossils had jumped from tray to tray, and many trays were in disarray. Some fossils had never been catalogued in the first place, just parked in the drawers to await someone like me, and I had to sift through file cabinets of notes and locality information to piece together their basic stories. Paleontological research is not a particularly invasive practice, but over a time horizon of decades the collection stirs as if by convection. Entropy enters.

The attention of people erodes order in the cabinets. And yet it is the attention of people that attempts order in the first place, giving every fossil its label along with the hope that it will contribute to a collective understanding.

Especially vexing were the fossils without any label at all. They were beautiful objects, mahogany-rich and fluted in baroque styles, speaking of past lives and the possibility, however remote, that some things in life might last. But lacking any data about where they had been found, and when, and in what layer of the earth, they could not contribute to the collection. Several times I took small loads of them up the elevator and into the sunlight. I walked them carefully to the dumpster and set them on the lid. I fingered through them one last time. It felt like sacrilege to tip them in.

photo by John F. Williams

photo by John F. Williams

The old brick Burke Museum itself has since been reduced to dust. The collections have been moved to the new museum building. I have moved.

In January it rained five inches in thirty-six hours, the rain an atmospheric river from the far side of the Pacific. I lay awake all night hearing it move in waves over the metal roof of this house. A few weeks before, a landslide had ripped a gash in a nearby gully, revealing that a hillside of ferns was nothing more than a foot-thick skin on a planet of glistening earth. As the waves of rainwater poured into the land around the house, the knowledge of mud haunted me. I could not stop thinking about the weight of water, its lubrication, how it was sliding through pores in all the strata we cannot measure.

The force of disintegration is always at hand. And it comes paired with the unknown.

If the house slid, how fast would it go? Would the whole thing go? Would it give us any warning? If we felt the first tremor, would we have time to dash outside? What then? Half-naked in the rain, would we know safe ground when we reached it? If we were still inside the house, would it be a soft ride to the beach or a crushing thing? Could we climb away if we were surrounded by liquified earth? Would it swallow us? Fossilize us?

The coastal engineer had told us that the hillside under the house would fail — they just couldn’t say if it would be in ten years or ten thousand years.

Where is the house that will last? What scheme of order can invent it?

Those last questions did not occur to me that night. Nor do they seem worth asking now. As I tossed and turned and got up to peer into the dark, I was concerned with details: pathways, flashlights, the exact orientation of shoes. The holding power of roots. The situation as it stood, imperfect, unknown, fraught. We cannot acid-wash our homes of the muddy world, nor fully purify them into mathematics. We build upon a meandering path.

Even shells, the most solidly protective of houses, integrated as they are with their creators and shaped for their environments, cannot rely fully on mathematics for their design. The world requires improvisation. Moon snails arrive. Raup acknowledged that his models could not account for things like growth lines and ornamental spires. He discussed clams. If their two shells, expanding in opposite spirals, were to follow simple geometry, the knobs where they began, overlapping, would prevent the animal from ever closing. Clams have solved this by leaning the generating curve for their shells at an angle. When the two shells meet, they fit perfectly. Furthermore, they have developed along their hinges a number of interlocking and asymmetric teeth to give the joint strength.

Thus clams are remarkably effective at inhabiting the beaches I walk. And none of their shells last. No structure lasts. And yet we must build them.

Even as I wrote this essay, absently fingering my shell collection as I attempted to find form in sentences and syntax, one of my smallest shells broke like a dry pine needle. It is a thin clam shell from the Bering Sea. Drilled in its center is the hole from a northern cousin to our moon snail. The shell did not break straight across. The fracture ran in a semicircle along a growth line until it jumped perpendicularly to the edge of the shell.

Needless to say, I’ve kept it in my collection.

Chris Rurik is a writer and naturalist who lives on a fourth-generation family farm on the Key Peninsula. His work focuses on interactions between human perception and the wider living world. You can read his monthly essays in the:

.

Table of Contents, Issue #12, Summer 2021

Beach Wrack

by Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedby Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedOn a warm sunny day, the shores of Puget Sound are filled with the smell of rotting seaweed. Flies are heard before they are seen, swarming above...

Hermit Crabs

by Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensenby Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensen The waves fly onto the beach as if they were racing each other. Which one can...

Piling Up

by Jeff Adams, Summer 2021 photos by Jeff Adams except as noted fact checked by Andy Lambphoto by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Jeff Adams, Summer 2021 photos by Jeff Adams except as noted fact checked by Andy LambAs a marine ecologist and nature...

RVs of the Beach

by Tom Noland, Summer 2021 photos by Tom Noland except as noted fact-checked by Greg Jensenby Tom Noland, Summer 2021 photos by Tom Noland except as noted fact-checked by Greg JensenWalking the shore of Cama Beach State Park on one of the lowest tides in recent...

Moon Snails at Low Tide

by Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyBy Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyAt the end of May, we had two days of minus 3.8’ (minus 1.15 m) tides at the northern end of the Kitsap Peninsula; wonderful for...

A Rainbow of Crabs

by Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen photo by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen On a Saturday in early March, in an attempt to shake off the last of the winter lockdown slump, my partner...

Poetry-12

Summer 2021Photo by Jessica C. LevinePhoto by Jessica C. LevineSummer 2021To begin this section of poetry, here are three haikus which speak to our excessive heat this summer.by Drea Dangerton Cold water absentDrive belt for water massesFrayed, hardly churning...

Hello Under There

Proper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 photo by Kaylani Siplinphoto by Kaylani SiplinProper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 At first glance, the beaches along the Salish Sea may seem desolate, except for the...

Home Sweet Home

by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021 Photos by Barbara Erickson except as noted by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021 Photos by Barbara Erickson except as notedWHOOPEE! With the approach of summer and loosening of COVID restrictions, it’s time to head out exploring! For me,...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.