PILING UP

by Jeff Adams, Summer 2021

photos by Jeff Adams except as noted

fact checked by Andy Lamb

photo by John F. Williams

photo by John F. Williams

PILING UP

by Jeff Adams, Summer 2021

photos by Jeff Adams except as noted

fact checked by Andy Lamb

As a marine ecologist and nature superfan, exploring natural beaches is one of my greatest joys. Experiencing natural beaches affords us the opportunity to not only think about connections and processes at different scales, but about the period of time over which beaches have been developing since the end of the last ice age. Yet, many Salish Sea beaches aren’t entirely natural anymore. While infrastructure does change shoreline ecosystems, it can provide a focused window into the complexities of making a home between the tides. One relatively common and accessible group of structures to explore on a low tide are pilings, the tall pieces of tree or metal or concrete that have long supported our desire to extend our lives and activities from our terrestrial constraints out over the water.

The rich collection of sea life, for which Salish Sea beaches are home, is shaped by the environment and life around it — from the complex interactions between predators, prey, parasites, or passersby, to the pressures of the physical world’s pummeling, heating, cooling, drying, or irradiation, or to the consequences of chemistry, with oxygen, pH, pollution, and nutrients supporting or interfering with life processes.

Pilings focus the ecological effects connected to the rise and fall of the tides into a fairly narrow, often cylindrical home that is much more high-rise apartment than ranch-style house. Who can live on which floors of this apartment is very much dictated by interconnected biological, physical, and chemical processes.

Let’s consider a piling near the water’s edge when the tide is really far out, an extreme low tide. Just six hours earlier and six hours later, the water may be as much as 20 feet higher in parts of South Puget Sound, 16 feet in Central Sound or Hood Canal, and 12 feet in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Even at 12 feet, that’s a lot of real estate!

The sea life near the top of the piling high rise, where the water reaches highest, spend much of their time out of the water and have to be able to survive the physical pressures of being high and dry or blasted by sun, heat, cold, rain, or whatever the above world can throw at them. They may also have to be able to survive on infrequent meals. For instance, a plankton eater can only eat when covered in water, and animals at upper edges of the tide may only be under water briefly each day or even less than daily. Upshots of living near the top of the high rise are less competition for space and potentially less predation. Lots of marine predators, like sea stars, won’t have enough time to eat you when the water is in or simply won’t go higher than the floors on which they’re safe from exposure.

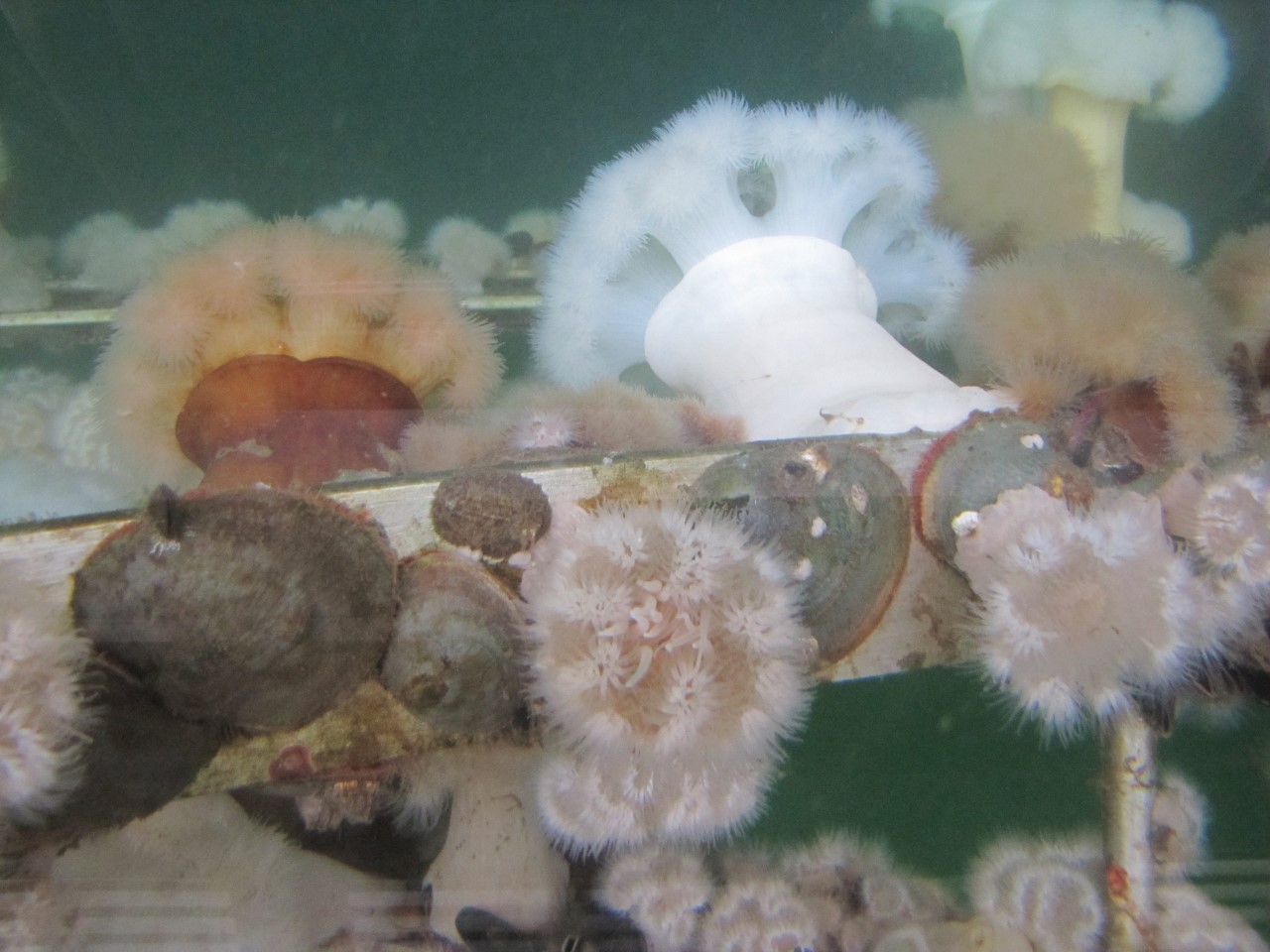

One photo shows plumose anemones hanging when the tide is out, the other shows plumose anemones when they are submerged.

In the middle floors of the piling apartment, species are subject to the stressors and benefits of both the higher and lower tides and adapt to both. In the lower floors, sea creatures are generally sensitive to being out of the water for very long and are under more pressures from predation and competition for space and food.

Plumose anemones are mostly made of water and feed on plankton. Of the two plumose anemone species in the Salish Sea, the smaller one can close up and hold water, allowing it to live more easily in the middle to low floors of the apartment. The larger anemone species that grows up to three feet long generally dwells in the safety and constant food supply of the basement, below the lowest tides. The pattern of larger species living lower is not unique to anemones.

Barnacles are a prominent part of the piling community and a good example of the responses we’ve been exploring here. A tiny barnacle, with an oval opening and smaller than a pea, mixes with but generally lives higher than the others and is called the little brown barnacle. In the middle and lower floors, you find the well-known, marble-sized acorn barnacle, with its diamond-shaped opening. In the lower floors, you also find the thatched or haystack barnacle, our second largest, that can grow as big as a tennis ball.

Thatched or haystack barnacles. The second second largest species in the Salish Sea, after the giant barnacle, which is mostly found below the lowest tides.

Along with mussels, barnacles often provide a foundation for the communities that live on habitats like pilings. While they prey only on tiny plankton, all sorts of things, from burly sea

stars and stout snails to delicate ribbon worms, love to eat barnacles. The higher barnacles live on the piling, the fewer predators they’ll have to deal with. Competition for space is another biological factor that affects how barnacles fit within the piling community. Acorn barnacles can survive being overcrowded and just grow up tall and skinny, while haystack and little brown barnacles need more space and may not survive being crowded.

See more about barnacles in the article:

See more about barnacles in the article:

The Barnacle — More Than Meets The Eye

While usually situated a bit lower than the animals, the seaweeds can also occupy different floors of the piling apartment. Often red and green seaweeds will inhabit the middle floors, and the more sensitive brown kelps dwell near the lowest tides where they’re exposed to the elements less often. These patterns are similar to the tidal zones you can see stretched from top to bottom of a beach, but just concentrated in a small, vertical space on a piling. Some pilings have very few seaweeds or only small ones hanging out in cracks and crevices. Really small algae, called diatoms, occupy surfaces of pilings and may even be farmed by limpets that keep their little territories free of barnacles so they can scoot around and dine on diatoms.

See more about limpets in the article:

See more about limpets in the article:

Home Sweet Home, Limpet Style by Barbara Erickson

Limpets and barnacles high on a glacial erratic. photo by John F. Williams

Limpets and barnacles high on a glacial erratic. photo by John F. Williams

So many interactions in such an observable space! Explore pilings next time you’re near a pier or on a dock at low tide, or in a place where pilings are the relics of some past structure. Fewer and farther between, glacial erratics provide a similar experience on a more natural substrate. Look slowly, closely, and curiously, imagining what interactions and pressures the sea life you observe may be adapted to and living under. Whether you step back and look across all Salish Sea beaches, consider a single place, ponder a particular habitat, focus on a specific rock, or identify an individual organism, these complexities come into play at all scales. Take a moment or many and wonder at all this ecological connectedness. (Breathe deeply… exhale.)

Love it.

Table of Contents, Issue #12, Summer 2021

Beach Wrack

by Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedby Nick Baca, Summer 2021 photos by Nick Baca except as notedOn a warm sunny day, the shores of Puget Sound are filled with the smell of rotting seaweed. Flies are heard before they are seen, swarming above...

Hermit Crabs

by Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensenby Sadie Bailey, Summer 2021 photos and drawings by Jan Kocian fact checked by Greg Jensen The waves fly onto the beach as if they were racing each other. Which one can...

RVs of the Beach

by Tom Noland, Summer 2021 photos by Tom Noland except as noted fact-checked by Greg Jensenby Tom Noland, Summer 2021 photos by Tom Noland except as noted fact-checked by Greg JensenWalking the shore of Cama Beach State Park on one of the lowest tides in recent...

Shell Shapes

by Chris Rurik, Summer 2021photo by Sarah Cavanaughphoto by Sarah Cavanaughby Chris Rurik, Summer 2021 Photos by Sarah CavanaughI have a collection of broken shells. They litter my desk and drawers, wave-smoothed fragments of curves and spirals, half-bleached, like...

Moon Snails at Low Tide

by Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyBy Marilyn DeRoy, Summer 2021 Photos & video by Marilyn DeRoyAt the end of May, we had two days of minus 3.8’ (minus 1.15 m) tides at the northern end of the Kitsap Peninsula; wonderful for...

A Rainbow of Crabs

by Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen photo by John F. Williamsphoto by John F. Williamsby Laura Marx, Summer 2021 fact-checked by Greg Jensen On a Saturday in early March, in an attempt to shake off the last of the winter lockdown slump, my partner...

Poetry-12

Summer 2021Photo by Jessica C. LevinePhoto by Jessica C. LevineSummer 2021To begin this section of poetry, here are three haikus which speak to our excessive heat this summer.by Drea Dangerton Cold water absentDrive belt for water massesFrayed, hardly churning...

Hello Under There

Proper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 photo by Kaylani Siplinphoto by Kaylani SiplinProper Etiquette for Exploring the Beach by Sarah Lorse, Summer 2021 At first glance, the beaches along the Salish Sea may seem desolate, except for the...

Home Sweet Home

by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021 Photos by Barbara Erickson except as noted by Barbara Erickson, Summer 2021 Photos by Barbara Erickson except as notedWHOOPEE! With the approach of summer and loosening of COVID restrictions, it’s time to head out exploring! For me,...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.