A HUGE ICE AGE FLOOD INTO THE SALISH SEA

by JOHN J. CLAGUE and NICHOLAS J. ROBERTS, Spring 2021

The longest river in British Columbia twists through the Fraser Canyon and past the town of Hope. Photo by Michael A. Thornquist, Seaside Signs.

The longest river in British Columbia twists through the Fraser Canyon and past the town of Hope. Photo by Michael A. Thornquist, Seaside Signs.

A HUGE ICE AGE FLOOD INTO THE SALISH SEA

by JOHN J. CLAGUE and NICHOLAS J. ROBERTS, Spring 2021

editor’s note

Long ago, dams of glacier ice blocked river valleys in the Salish Sea region and beyond. These icy dams blocked rivers, creating glacial lakes behind them (similar to how a modern concrete dam forms a reservoir). Some of these glacial lakes were enormous, and when the ice began to melt and the ice dams failed, the water in those glacial lakes broke free and roared across the landscape in catastrophic megafloods. The Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington are a well-known example of how these floods shaped the land — the scablands were carved by repeated floods from Glacial Lake Missoula. Less well known is the glacial flood history of the Salish Sea region west of the Cascades. This article explores one of these megafloods that extended from western Canada down into northwest Washington State. It has taken detective work worthy of Sherlock Holmes for scientists to figure out what happened thousands of years ago when a giant British Columbia ice dam broke.

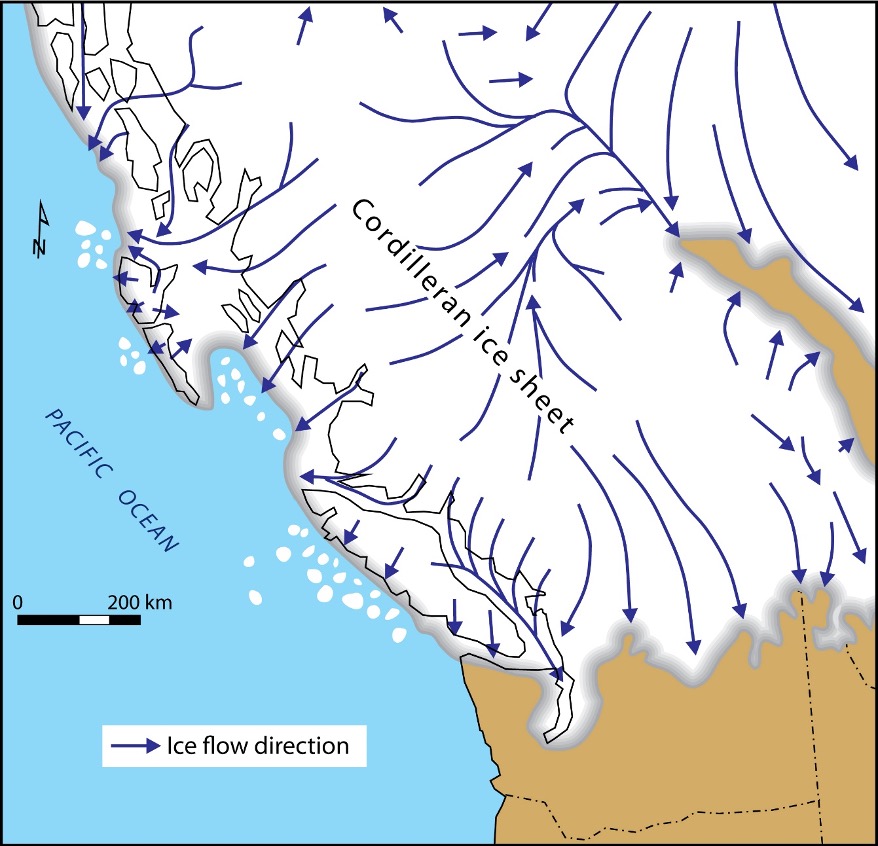

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing the southern part of the Cordilleran ice sheet at its maximum extent about 16,500 years ago. The southernmost extent of the ice sheet into Puget Sound, called the Puget Lobe, is the subject of other articles in this issue of Salish. Map courtesy of Richard Franklin.

leading up to a megaflood

The Fraser River watershed is one of the largest in North America, with an area equal to nearly one-quarter of the surface area of British Columbia. The river flows nearly 700 km (430 miles) from its headwaters in the central Rocky Mountains of BC to its mouth on the Strait of Georgia at Vancouver.

The flood described in this article traveled down the Fraser River valley near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, often referred to as the “Ice Ages,” a period of recurrent continental glaciation from about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. Just before the Fraser River flood, BC and southern Yukon were covered by the Cordilleran ice sheet (Figure 1). This large ice sheet covered nearly all of BC, extending west across the BC continental shelf and south into northern Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

About 16,500 years ago, the Cordilleran ice sheet began to melt away. The southern Coast Mountains of BC remained ice-covered for another several thousand years, but about 12,500 years ago glaciers moved back down from the mountains into the valleys north and east of Vancouver. At the same time, a labyrinth of dead or dying tongues of glacier ice remained in many interior valleys, forming temporary glacier-dammed lakes. The largest of these lakes is known as Glacial Lake Fraser (Figure 2). The lake at the ice dam eventually reached more than 250 m (820 feet) deep and covered about 2,500 km2 (nearly a thousand square miles) of central British Columbia.

Figure 2. Map of the Fraser River watershed showing Glacial Lake Fraser prior to the megaflood about 11,500 years ago. The inset shows the location of Fort Langley, BC, and Lynden, Washington, which are featured in Figure 5. Map courtesy of Nick Roberts.

the megaflood breaks free

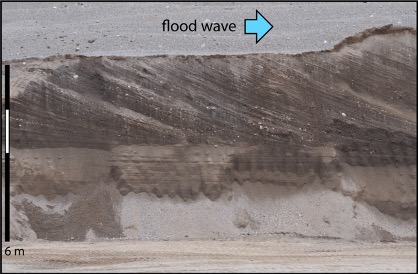

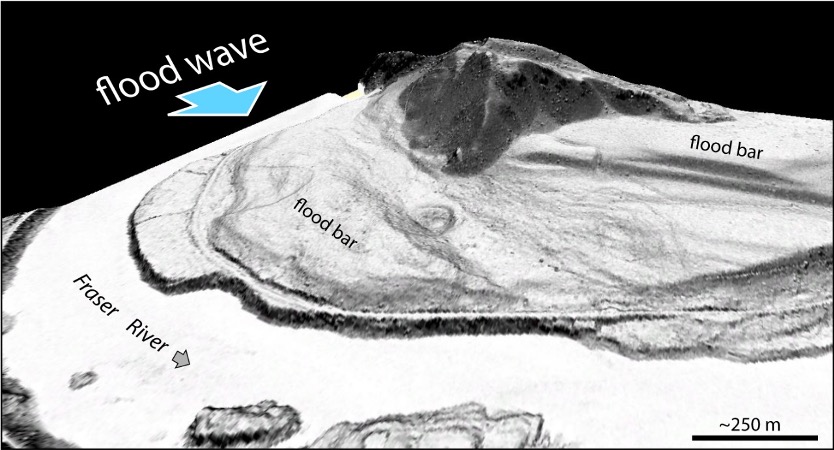

About 11,500 years ago, the weakened glacier dam failed and the flood of water from Glacial Lake Fraser traveled 330 km (200 miles) southward to Hope and from there west into the Salish Sea. South as far as Hope, the flood was confined within a narrow valley, and the flood wave left spectacular whaleback-shaped bars of gravel and boulders (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Oblique Lidar digital elevation model (DEM) of flood-sculpted terrain in the Fraser Canyon north of Hope. View to the northeast. For more about Lidar and how it’s being used to better understand our local geologic history, see Lidar | WA – DNR. Image courtesy of Nick Roberts.

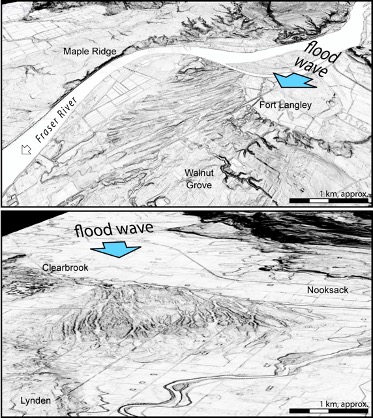

The flood waters didn’t stop there. When the flood wave left the narrow Fraser Canyon, the water spread and slowed, but large lowland areas from Vancouver south to Bellingham, Wash. were still overrun by the flood. It appears the floodwaters followed two paths in the western Fraser Lowland: one south of Sumas Mountain, across Sumas Prairie, and into the Salish Sea at Bellingham; and the other north of Sumas Mountain, past Fort Langley, and into the Salish Sea just south of Vancouver. Sand deposits west of Hope (Figure 4) and flood-scoured surfaces in the Fraser Lowland near Lynden, Washington, and Fort Langley, BC (Figure 5) provide evidence of the flood’s passing.

We speculate that humans lived along the shores of the Salish Sea at the time of the megaflood. Although we have no direct evidence for this, human footprints to the north on the central BC coast have been dated to about 13,000 years ago. In any case, the flood must have been an immense, roaring wall of water. We estimate that its peak discharge at Hope was about four times the mean discharge of the Amazon River.

Figure 4. Photo of flood-deposited sediments underlying a terrace just south of the Trans-Canada Highway west of Hope, BC. Note the scale bar at the left side of the photo. Photo by John Clague.

Figure 5. Oblique Lidar DEMs of flood-scoured glaciomarine sediments near Fort Langley, BC (top) and Lynden, Washington (bottom). Image courtesy of Nick Roberts.

determining the age of the flood

How do we know when the Glacial Lake Fraser megaflood happened? Through scientific detective work. Along with studying deposits of sediments and rocks in the landscape, scientists also use radiocarbon dating and terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide (TCN) dating to find clues. Radiocarbon dating measures the decay of a certain type of carbon isotope in fossilized plants and animals to estimate the amount of time that’s passed since the organism died. TCN dating estimates how long rocks have been at the ground surface where they are exposed to cosmic rays that affect certain isotopes in the rocks.

Some 20 years ago, researchers obtained radiocarbon ages on marine shells and wood fragments from sediments in Saanich Inlet on the west side of the Salish Sea. The sediment also contained fossil pollen eroded from sedimentary rocks found only on the BC mainland near Vancouver. This finding, together with the unique characteristics of the sediment, suggested that a flood carried large amounts of sediment across the Fraser Lowland into the Salish Sea. Putting together the sediment, the pollen, the radiocarbon ages on the shell and wood in the Saanich Inlet sediment, and the TCN ages of boulders along the flood path, scientists have deduced that the flood happened about 11,500 years ago.

John J. Clague is an emeritus professor in the Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC. He is one of Canada’s leading authorities in Quaternary and environmental earth sciences. In addition to publishing 300 papers, reports, and monographs on a wide range of earth science topics, John provides interviews and materials (such as this article) that are understandable and interesting to the public. His research on earthquakes, landslides, and floods has greatly increased public and official awareness of these hazards.

Nicholas J. Roberts is a natural hazards geologist at Mineral Resources Tasmania and an adjunct professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at Simon Fraser University. His research spans natural hazards, Quaternary geology, paleomagnetism, and Earth’s past magnetic field. Together these insights help reduce hazard losses and understand geologically recent climatic variability. In addition to his recent collaboration with John Clague, Nick’s 50 scholarly publications cover topics such as vulcanism, landslides, tsunamis, and glacial history.

FIND OUT MORE

Readers who would like more information on the Fraser River megaflood are referred to an article published in the journal Geomorphology:

Clague, J.J., Roberts, N.J., Miller, B., Menounos, B., and Goehring, B. 2020. A huge flood in the Fraser River valley, British Columbia, near the Pleistocene Termination. Geomorphology, v. 374, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107374

The editor also recommends these web pages for more about ice age floods in the Pacific Northwest and other places (maybe even on Mars?):

Explore the Ice Age Floods with 12 New IAFI Brochures – Ice Age Floods Institute

Table of Contents, Issue #11, Spring 2021

WA Megafauna

by Thomas Noland, Spring 2021 Photos by Thomas Noland at the Burke Museum in Seattleby Thomas Noland, Spring 2021 Photos by Thomas Noland at the Burke Museum in SeattleWe’ve been lucky to find remnants of really big creatures from the past here in Washington. Not...

Whidbey Island Kettles

by Sadie Bailey, Spring 2021 Photos & video by Tom Noland except as notedby Sadie Bailey, Spring 2021 Photos & video by Tom Noland except as noted I have always loved cloudy days. The kind of days where the grey takes over the color of the world. Where the...

Poetry-11

Spring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsSpring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsShe feels the heat by Janet Knox From deep below groundDegrees add degrees the deeperHeat of exhaust bodies degassingIn cars like coffins the heat of ageDone with pregnant possibilityHer body...

Our Icy Past

by Nancy Sefton, Spring 2021 Photos by John F. Williamsby Nancy Sefton, Spring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsFerries are an integral part of today’s Salish Sea region. But thousands of years ago, you could have simply walked across the Salish Sea, that is, if you...

Riches of the Prairies

by Sarah Hamman, Spring 2021Taylor's checkerspot butterfly visiting a balsamroot flower. Photo by Sarah Hamman.by Sarah Hamman, Spring 2021The geologic history of the Puget Lowlands is filled with drama — multiple glacial advances, glacial outburst floods, tectonic...

Language of Glaciers

by Chrys Bertolotto, Spring 2021 Photo by Tom Nolandby Chrys Bertolotto, Spring 2021 Photo by Tom NolandGlaciers are such immensely powerful rivers of ice that they shape landscapes in their path. They have done this to such a degree that new words needed to be...

Videos-11

Spring 2021 Photo by Cookie the Pom on UnsplashSpring 2021 Photo by Cookie the Pom on UnsplashYes, that's Videos-11, not Oceans Eleven. These are some videos that illustrate some of the ideas discussed in the articles and poems in Salish Magazine issue number 11....

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.