WASHINGTON'S MEGAFAUNA: REALLY BIG CREATURES FROM THE PAST

by Thomas Noland, Spring 2021

Photos by Thomas Noland at the Burke Museum in Seattle

WASHINGTON'S MEGAFAUNA: REALLY BIG CREATURES FROM THE PAST

by Thomas Noland, Spring 2021

Photos by Thomas Noland at the Burke Museum in Seattle

We’ve been lucky to find remnants of really big creatures from the past here in Washington. Not dinosaurs — their fossils are much older and rare in this state — but other really big creatures known as the megafauna that lived in the Salish Sea region thousands of years ago.

Within the past several decades, scientists have learned startling new things about the Salish Sea megafauna and their relationship with early humans. Much of the evidence has been uncovered by accident, by people digging a farm pond or excavating a building site.

This article describes a few of the best-known megafauna of the Salish Sea region: ancient bison, American mastodon, Columbia mammoth, and giant ground sloth. And we can’t explore Washington’s megafauna without mentioning the saber-tooth salmon (I’m not making this up). Even though these creatures have been extinct for a long time in human terms, you can still see their fossils and learn about them at local museums and online.

The last ice age was during the Pleistocene Epoch, which lasted from roughly 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. There were seven periods during this time frame when the ice sheet melted and advanced. The last advance of the Cordilleran ice sheet covered Canada and some parts of the northern United States. In Washington state, the ice sheet was known as the Puget Lobe and it extended just past Olympia, covering all of what was to become Puget Sound.

As the icy Puget Lobe began melting around 15,000 years ago, nitrogen-fixing plants were able to recolonize the barren landscape that had been scoured by ice. Plants such as willows and alder were able to grow in. They were later followed by cottonwood, hemlock, and spruce forests. The plants provided food that allowed the enormous animals to move north into areas once blanketed in ice.

So now, on to the really big beasts and where you can still find them.

ancient bison (Bison antiquus)

The remains of ancient bison have been found at Ayer’s Pond on Orcas Island, where workers excavating a pond unearthed the bones in 2003. These creatures were the ancestors of today’s modern bison, and they were the most common large herbivore in North America for thousands of years. The ancient bison was up to 25 percent larger than a modern bison. Imagine a great shaggy beast up to 7.5 feet tall and 15 feet long, weighing around 3,500 pounds. From tip-to-tip, its horns measured around three feet.

The ancient bison remains, found on Orcas Island, are 12,000 to 14,000 years old. Pollen samples collected at archeological dig sites suggest that the vegetation in the San Juan Islands at that time consisted of open pine forests. The ancient bison probably fed primarily on low-growing herbs and shrubs such as buffaloberry, northern wormwood, and Sitka alder. Like the large herbivores of today (such as elk and deer), the ancient bison were likely an important part of the natural cycle, fertilizing the forest with their droppings, spreading plant seeds, and serving as food for predators and scavengers.

The ancient bison remains from Ayer’s Pond show signs of human butchering, providing very early evidence of human activity and human interactions with wild animals in the region. You can learn more about them at the Orcas Island Historical Museum, the Burke Museum in Seattle, and in this video:

Mossback’s Northwest | Bison Hunters in the San Juans | Season 4 | PBS

american mastodon (Mammut americanum)

In 1977, Emanuel Manis was working with a backhoe on his farm in Sequim when he unearthed the fossilized tusks of a mastodon buried under four feet of mucky wetland soil. This find was especially important because a spear point was embedded in a rib bone, and there was evidence of scoring with a tool on the tusks. This is one of the oldest sites in North America that shows human interactions with mastodons, dated at around 14,000 years ago. The archaeologists who soon descended on the site also found bison bones with signs of butchering, along with remains of caribou, birds, and other creatures.

Mastodons were shaggy, short legged, and heavily muscled. They were around seven feet tall at the shoulders for a female and up to nine feet for a male and weighed around 17,500 pounds (comparable to a modern male African elephant). Their enormous tusks (several feet long) may have been used in feeding and during mating challenges between males. They lived in social groups of females and young, similar to elephants today.

The American mastodon is thought to have browsed on shrubs near swampy areas such as the Manis site. They had pointy teeth that were good for breaking down woody plants.

You can see the artifacts of the Manis mastodon at the Sequim Museum and Arts Center. For a fascinating description and photos of the excavation, see this article:

columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi)

In January 2016, a partial skull of a Columbian mammoth was found in Sequim. Local hikers found the skull exposed in an eroding bluff. It was subsequently excavated by scientists from the Burke Museum. Just two years earlier, a Columbian mammoth tusk over eight feet long was found at a construction site in the South Lake Union area of Seattle. This species was so common in Washington state that it was designated as our state fossil in 1998.

The Columbian mammoth stood around 13 feet tall and weighed around 22,000 pounds. Their tusks curved toward each other until sometimes they crossed. Unlike the mastodon that browsed on woody shrubs, mammoths grazed on sedges and grasses. Their teeth were flat and ridged, good for grinding grassy vegetation. The web page below compares these two elephant-like creatures:

Mastodon or Mammoth? (U.S. National Park Service)

The Burke Museum has a collection of Columbian mammoth fossils including tusks and teeth. The web link below tells the story of the find at Sequim, with photos of the archaeologists excavating and preserving the fossils:

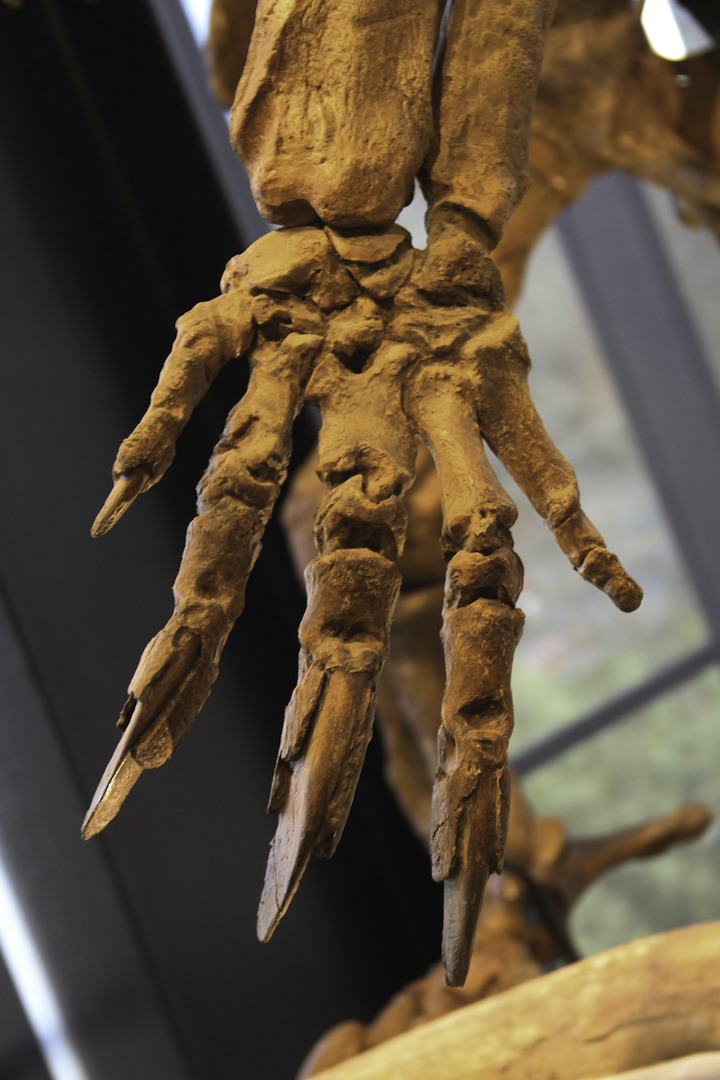

giant ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii)

The giant ground sloth lived in North and Central American forests until about 11,000 years ago. They were 10 feet tall and up to the size of a modern elephant. They lived on the ground, not in trees like today’s sloths.

As the ice melted away, pines, grass, and shrubland vegetation grew into the newly exposed ground. This allowed the herbivorous giant ground sloth plenty of food to eat with their peg-like teeth and enormous claws. Strong hind legs allowed them to rear up and strip vegetation from trees.

The well-preserved bones of a giant ground sloth were found in a peat bog near SeaTac during the construction of a runway in the 1960s. This sloth died around 13,000 years ago. You can see a mounted display of the SeaTac sloth skeleton at the Burke Museum and this web page tells the story:

Construction at Sea-Tac Airport unearths an extinct giant sloth on February 14, 1961

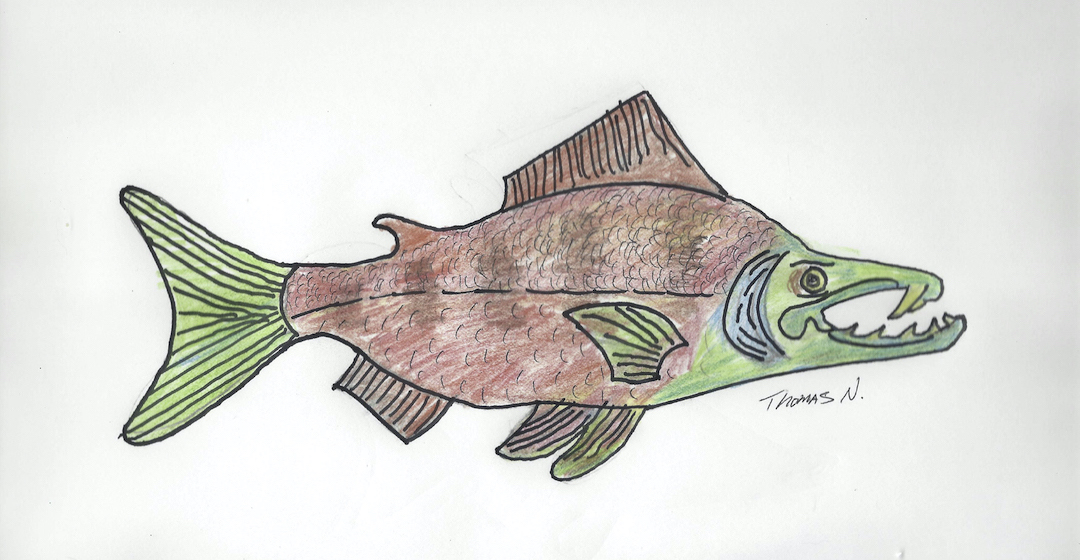

saber-tooth salmon (Onchorhynchus rastosus)

Imagine a salmon six to eight feet long weighing 400 pounds, with tusk-shaped teeth over an inch long protruding from its upper jaw. These saber-tooth salmon once swam in the coastal waters of the Pacific Northwest. Scientists believe the ancient salmon’s saber teeth were used during the mating season and that these giants fed on plankton.

Salmon evolved millions of years ago when the climate was warmer. Some species, such as the saber-tooth salmon, didn’t survive the ice age. However, in the Salish Sea region, salmon were able to move in as the glaciers retreated. In fact, the geologic forces that sculpted our landscape — glaciers, lahars, volcanos, erosion — may have shaped the evolution of the six different salmon species we have here today.

Salmon colonize the Puget lowland about 14,900 years ago

The Oregon University Museum of Natural and Cultural History has an extensive exhibit on the saber-tooth salmon. You can visit the exhibit online at this link:

what happened to the really big beasts?

The giant mammals roamed the Salish Sea landscape for thousands of years. Around 10,000 years ago, they disappeared. Their extinction is part of a pattern of disappearing megafauna across North America around that time. Scientists have several theories about why they went extinct: climate change, hunting by humans, and other causes. For a fascinating discussion, check out “End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World’s Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals” by Ross D.E. MacPhee and this video:

10 extinct giants that once roamed North America | Live Science

Thomas Noland is a naturalist and photographer living in Everett. In addition to his interests in paleobiology, he is a dedicated entomologist and caretaker of numerous rescued cats.

Table of Contents, Issue #11, Spring 2021

Huge Ice Flood

by JOHN J. CLAGUE and NICHOLAS J. ROBERTS, Spring 2021The longest river in British Columbia twists through the Fraser Canyon and past the town of Hope. Photo by Michael A. Thornquist, Seaside Signs.The longest river in British Columbia twists through the Fraser Canyon...

Whidbey Island Kettles

by Sadie Bailey, Spring 2021 Photos & video by Tom Noland except as notedby Sadie Bailey, Spring 2021 Photos & video by Tom Noland except as noted I have always loved cloudy days. The kind of days where the grey takes over the color of the world. Where the...

Poetry-11

Spring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsSpring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsShe feels the heat by Janet Knox From deep below groundDegrees add degrees the deeperHeat of exhaust bodies degassingIn cars like coffins the heat of ageDone with pregnant possibilityHer body...

Our Icy Past

by Nancy Sefton, Spring 2021 Photos by John F. Williamsby Nancy Sefton, Spring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsFerries are an integral part of today’s Salish Sea region. But thousands of years ago, you could have simply walked across the Salish Sea, that is, if you...

Riches of the Prairies

by Sarah Hamman, Spring 2021Taylor's checkerspot butterfly visiting a balsamroot flower. Photo by Sarah Hamman.by Sarah Hamman, Spring 2021The geologic history of the Puget Lowlands is filled with drama — multiple glacial advances, glacial outburst floods, tectonic...

Language of Glaciers

by Chrys Bertolotto, Spring 2021 Photo by Tom Nolandby Chrys Bertolotto, Spring 2021 Photo by Tom NolandGlaciers are such immensely powerful rivers of ice that they shape landscapes in their path. They have done this to such a degree that new words needed to be...

Videos-11

Spring 2021 Photo by Cookie the Pom on UnsplashSpring 2021 Photo by Cookie the Pom on UnsplashYes, that's Videos-11, not Oceans Eleven. These are some videos that illustrate some of the ideas discussed in the articles and poems in Salish Magazine issue number 11....

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.