OUR ICY PAST

by Nancy Sefton, Spring 2021

Photos by John F. Williams

OUR ICY PAST

by Nancy Sefton, Spring 2021

Photos by John F. Williams

Ferries are an integral part of today’s Salish Sea region. But thousands of years ago, you could have simply walked across the Salish Sea, that is, if you were a skilled ice climber!

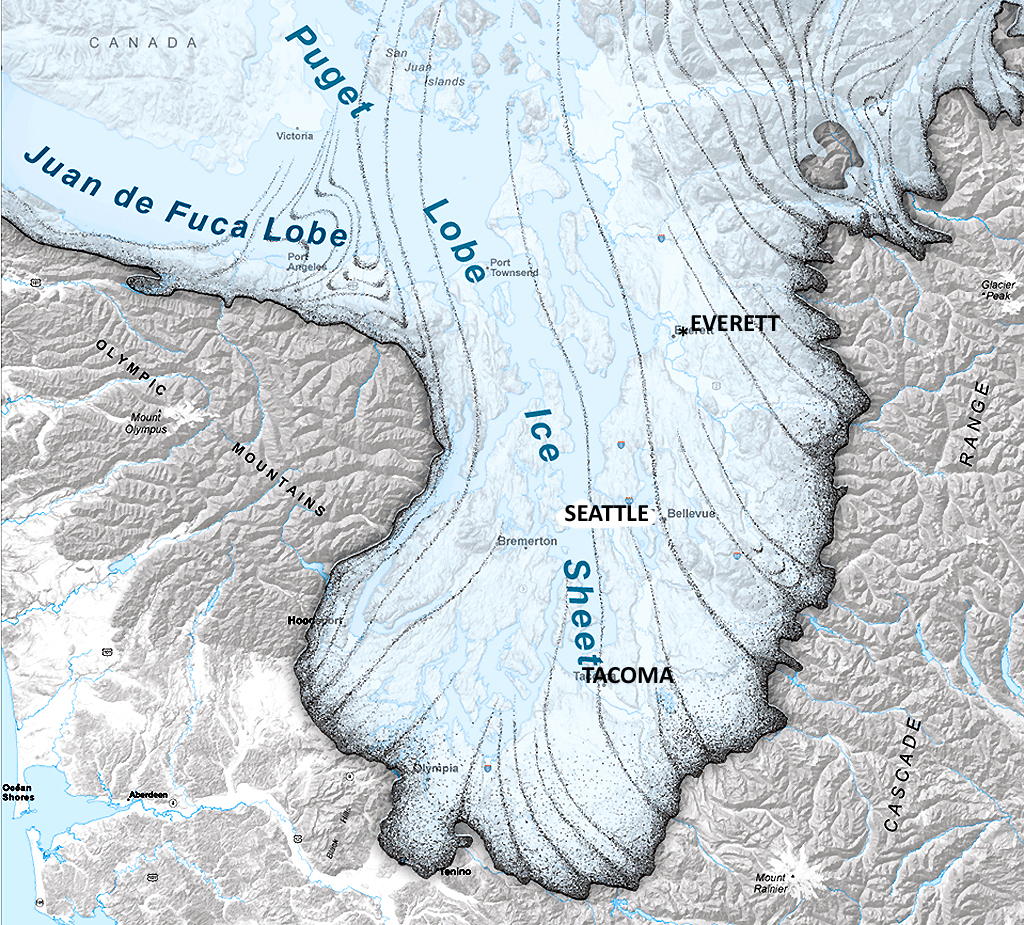

Back then, this area lay crushed below a creeping sheet of ice. Formed in Canada about 25,000 years in the past, part of it had slowly bulldozed its way south over the border as a powerful ice blanket thousands of feet thick known today as the Puget Lobe. As it crept steadily southward, the Olympic and Cascade mountain ranges on either side were barely visible above the marauding ice. The gravel, rocks, and boulders carried at the glacier’s base, along with gushing melt-water, relentlessly ground away at the terrain below.

When it finally moved over what is now downtown Seattle, the glacier grew in thickness until it was as tall as three Columbia Centers stacked on top of one another. (That’s over 3,000 feet!) As its overall shape, height, and weight increased over time, the terrain beneath was continuously carved, sculpted, and molded. Moreover, the ice had choked off the routes that water had taken from our area out to the Pacific Ocean. In other words, the Strait of Juan de Fuca was blocked, and melt-water had to flow south and down to the ocean through the Chehalis River valley.

Photo courtesy of Washington state Department of Natural Resources

Eventually, as our planet warmed, the Big Thaw began, and the moving ice at last came to a halt about a dozen miles south of what is now Olympia. As the frozen barrier melted and retreated over the next thousand years, the mighty Pacific Ocean could at last make its entrance. It slowly rolled in through an ice-and-boulder-carved trench above the Olympic Peninsula, to become the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Salt water also crept in to fill another gouge running northward into British Columbia: the Strait of Georgia.

The ice sheet advanced and retreated many times, each time digging out older glacial material and depositing a new layers. When the last ice sheet melted back to the north, it left behind a host of giant boulders (“glacial erratics”). Many erratics can be seen today in their final resting places.

As the climate warmed, the land rebounded slowly from the weight of the ice, rising hundreds of feet and gradually exposing the complex Pacific Northwest terrain we know today. Our regional saltwater byways are now referred to as the Salish Sea, after our local native tribes. (The Coast Salish people occupied these shores long before George Vancouver arrived with his tall ships.) Because the ice sheets left so much sediment behind, shorelines in this region are composed primarily of sand, gravel, cobbles, and mud.

Although plate tectonics played a role in shaping the broad troughs extending from the Puget Lowland up through the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca, the glacial ice sheet left us with the more intricate channels of Hood Canal, Puget Sound, Lake Washington, and Lake Sammamish as part of its legacy. Today, these waters are heavily traveled by cruise ships, ferries, fishing boats, tankers, and pleasure craft ranging from giant yachts to kayaks and canoes.

Lands to the east of the Salish Sea also showcase our glacier’s travels. A drive into the Cascade Range reveals the effects of moving ice; as the glacier crept south, it dammed up the lower ends of several river valleys that ultimately filled to become today’s mountain lakes. A particularly scenic stretch lies between Seattle and the town of North Bend, where ancient ice carved the terrain in dramatic fashion.

Thus the forces of a historic glacier influenced northwest topography: where we build, where rivers empty into the Salish Sea, where wetlands lie, where harbors offer safe haven, where fish return upstream to spawn. Northwest residents are privileged to live in a unique water wonderland carved by ice.

And for a brief video tour or all of this, geologist Greg Geehan shows the landscape carved by glaciers 17,000 years ago. This 2 minute extract comes from just one chapter in an entrancing two hour video: The Geological Formation of Bainbridge Island. Find out about other chapters by visiting bainbridgegeology.com

Producer-Director: Cameron Snow; Lead-Camera: Cathy Bellefeuille

Nancy Sefton is an artist, writer, videographer and photographer who specializes in nature subjects. As a former diver she has contributed frequently to national magazines and newspapers, publishing over 300 articles about marine life. Nancy now lives in Poulsbo and writes for Sound Publishing newspapers.

Table of Contents, Issue #11, Spring 2021

Huge Ice Flood

by JOHN J. CLAGUE and NICHOLAS J. ROBERTS, Spring 2021The longest river in British Columbia twists through the Fraser Canyon and past the town of Hope. Photo by Michael A. Thornquist, Seaside Signs.The longest river in British Columbia twists through the Fraser Canyon...

WA Megafauna

by Thomas Noland, Spring 2021 Photos by Thomas Noland at the Burke Museum in Seattleby Thomas Noland, Spring 2021 Photos by Thomas Noland at the Burke Museum in SeattleWe’ve been lucky to find remnants of really big creatures from the past here in Washington. Not...

Whidbey Island Kettles

by Sadie Bailey, Spring 2021 Photos & video by Tom Noland except as notedby Sadie Bailey, Spring 2021 Photos & video by Tom Noland except as noted I have always loved cloudy days. The kind of days where the grey takes over the color of the world. Where the...

Poetry-11

Spring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsSpring 2021 Photos by John F. WilliamsShe feels the heat by Janet Knox From deep below groundDegrees add degrees the deeperHeat of exhaust bodies degassingIn cars like coffins the heat of ageDone with pregnant possibilityHer body...

Riches of the Prairies

by Sarah Hamman, Spring 2021Taylor's checkerspot butterfly visiting a balsamroot flower. Photo by Sarah Hamman.by Sarah Hamman, Spring 2021The geologic history of the Puget Lowlands is filled with drama — multiple glacial advances, glacial outburst floods, tectonic...

Language of Glaciers

by Chrys Bertolotto, Spring 2021 Photo by Tom Nolandby Chrys Bertolotto, Spring 2021 Photo by Tom NolandGlaciers are such immensely powerful rivers of ice that they shape landscapes in their path. They have done this to such a degree that new words needed to be...

Videos-11

Spring 2021 Photo by Cookie the Pom on UnsplashSpring 2021 Photo by Cookie the Pom on UnsplashYes, that's Videos-11, not Oceans Eleven. These are some videos that illustrate some of the ideas discussed in the articles and poems in Salish Magazine issue number 11....

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.