LICHENS

by Sara and Thomas Noland, Autumn 2019

Photo by John F. Williams

LICHENS

by Sara and Thomas Noland, Autumn 2019

In the fantastical world of fungus, it’s hard to stand out. But the lichens have managed to do just that.

You probably see lichens every day, whether in your yard, at the park, in the forest, or even walking down a city street. You can find lichens growing on rocks at the beach, on gravestones in a cemetery, on tree trunks, fence posts, and old cars. They inhabit extreme environments, from mountain peaks to shorelines; lichens dominate the Arctic tundra and are found in the Antarctic and in deserts. On some Puget Sound beaches, salt-tolerant lichens form characteristic bands of yellow, orange, and black on the rocks. Trees covered with lichens give our Northwest forests their magical character, softening the lines of trunks and adding delicacy to bare branches on a rainy winter day.

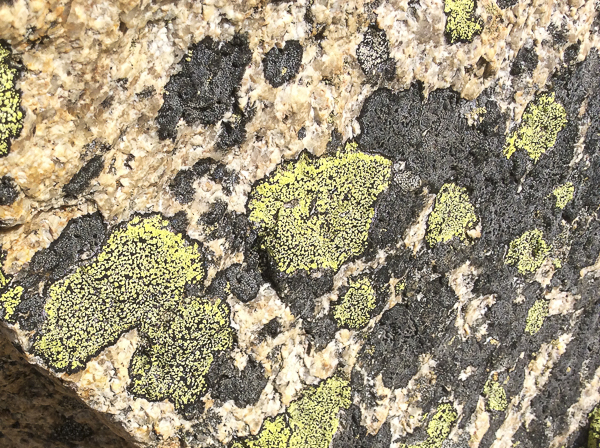

Yellow crustose lichen on a basalt boulder. Photo by Thomas Noland.

What is a lichen? Simply put, a lichen is a fungus plus one or more types of algae or blue-green bacteria that perform photosynthesis (that is, they use the energy of the sun to manufacture sugars, like green plants do). Around ten percent of lichens are “cyanolichens,” meaning they have blue-green bacteria as the photosynthetic partner. Some lichens have both green algae and a bacterial partner. The fungus and its algal/bacterial partner together form a complex structure (the lichen) that allows both partners to live in places they couldn’t inhabit on their own. The fungus dominates the relationship, giving the lichen its primary form and its name. The algal/bacterial partner is usually confined to a single layer of cells, whose color becomes more visible when the lichen is wet.

Lichens take on many different shapes and colors. Some forests lichens hang from tree branches like grizzled beards. Others form crusts that look like daubs of white paint or crazy orange graffiti. Still others might remind you of antler shapes, lettuce, or fairy-size teacups. Over 1,500 different lichens have been identified in the Pacific Northwest, with over 5,000 in North America and tens of thousands worldwide. New species are discovered every year.

Scientists (lichenologists) have divided lichens into three general groups based on their form: crustose (crust), foliose (leafy), and fruticose (shrubby or hairy).

Crustose lichens colonizing a piece of petrified wood. Photo by Thomas Noland.

A foliose species on a tree branch with brown reproductive structures like little cups. Photo by Thomas Noland.

Fruticose lichen on an alder branch. Photo by John F. Williams.

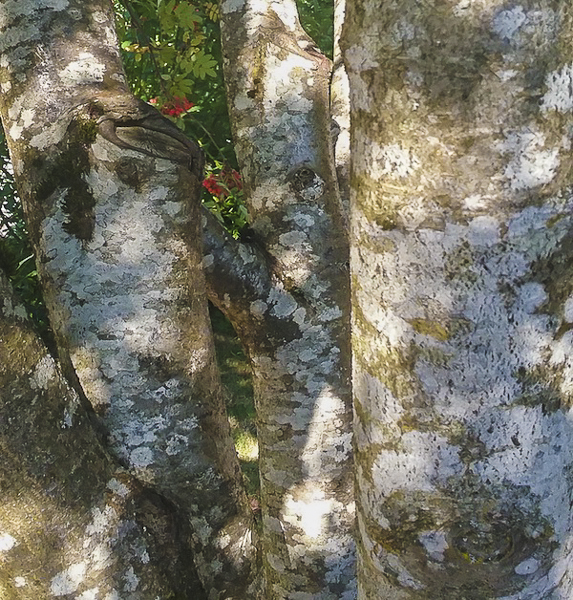

The crustose lichens encrust the surfaces of rocks, cemetery markers, tree trunks, and even rusty car wrecks. This lichen form ranges from plain white or gray to brilliant colors like deep oranges, yellows, and reds. The trunks of red alder, mountain ash, and other tree species can be covered by crustose lichens, turning them from brown to patterned white.

Pix to left: White crustose lichen splotches on the trunk of an alder tree. Photo by John F. Williams

The foliose lichens have two sides, a top and a bottom, often of different colors. They are sheet-like with numerous bumps and ridges and lobes. As Arthur Kruckeberg describes this group:

“Foliose lichens, those fringed, scalloped, or tattered sheets of plasticlike substance, are nature’s expression of crochet, needlepoint, and origami. They festoon the forest and decorate the forest floor in endless color, form, and texture.”

A local example from western Washington is Lobaria, known as lungwort lichen. Some of the lichens in this group are particularly sensitive to air pollution (discussed in more detail below).

Sunburst lichen (Xanthoria). Even though this lichen appears crust-like, the leafy lobes of a foliose lichen are visible. The cup-like structures are used for reproduction. It likes to grow where animals have been urinating. Photo by Thomas Noland.

Dog’s pelt lichen (Peltigera) on a tree in Renton Park, King County, Washington. This species absorbs nitrogen from the air and contributes it to the forest soil. Photo by Thomas Noland.

The fruticose lichens can look like miniature shrubs with round branches, or tangled beards hanging from tree branches, or tiny wine cups sticking up from a log. A common species is Letharia or wolf lichen, which contains a toxin called vulpinic acid that was historically used to poison wolves and foxes. One of the best-known lichens is a fruticose type commonly known as old man’s beard (Usnea), which can grow prolifically on old conifer trees.

Wolf lichen (Letharia), a fruticose species growing on conifers. Photo by Thomas Noland.

The hair-like lichen on this fallen alder tree branch is mostly old man’s beard (Usnea), a fruticose lichen. It’s sharing space with a white foliose (leafy) lichen and a bright green moss. As they decompose, lichens add nutrients to the forest soil. Photo by Thomas Noland.

These three groupings provide a way to study lichens based on their overall appearance. But what’s happening inside the lichen—how does the partnership work? A fungus on its own lacks chlorophyll (the pigment that is the engine of photosynthesis) and therefore can’t produce its own food. Unlike forest mushrooms that have various kinds of relationships with the trees themselves, these fungi take on a partner (algae or blue-green bacteria) that can manufacture sugar to feed them. Lichenized fungi can live in places lacking the nutrients a lone fungus would need to survive. (Around 20 percent of fungus species have become “lichenized,” meaning they occur as part of a lichen partnership.) For the algae/photosynthetic bacteria, which on their own need to live in water or wet areas, being part of a lichen means they have a moist, shady home provided by their fungal partner, and they too can also spread into areas they couldn’t inhabit on their own.

Bronze lichen sculpture by David Eisenhour, photo by Ann Welch.

You can learn more about forest mushrooms and their special relationships with trees in the article, Think Like a Mushroom in this issue

You can learn more about forest mushrooms and their special relationships with trees in the article, Think Like a Mushroom in this issue

Lichens don’t have deep roots to take up water in the way a tree or shrub does, and they lack a waxy coating as is found on the leaves of many plants. So how do they keep from drying out? Lichens can absorb water from rain, fog, or dew, but during a drought their water content can fall dramatically. At these dry times they enter a kind of dormancy until water is available again. In fact, alternating times of being dry and being wet appear to be important to the health of lichens, regulating the distribution of sugars between the algae/bacteria and fungus partners.

An assortment of lichen on a fallen tree. Photo by John F. Williams.

Sometimes you might find lichen perched on a large boulder. Find out more about our local boulders in the article Big Boulders in Issue #1.

Sometimes you might find lichen perched on a large boulder. Find out more about our local boulders in the article Big Boulders in Issue #1.

Lichens need other nutrients and minerals in addition to sugars. Some of these they can get from rain or even bird droppings. (Certain lichens are typically found on rocks favored by perching birds.) A few types of lichens absorb nitrogen from the air, bringing it into the forest ecosystem in a form that can be used by trees when the lichens fall to the forest floor and decompose. The relationship between trees and lichens is an intricate one. An old tree can support more than 30 different types of lichens, from those that require a moist, shady crevice to those that thrive on a sunny part of the trunk. Lichens grow slowly, and they don’t hurt the tree.

Lichens form an important ground cover in ecosystems such as southwest Washington prairies. Researchers have identified over 30 different groups of lichens in south Puget Sound remnant prairies, including rare reindeer lichens at Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve.

Mima Mounds prairie in southwest Washington. You can see ground-dwelling lichens if you walk the trails through this natural area preserve. Photo by Thomas Noland

Cyanolichens are very important to biological soil crusts. In the arid lands of eastern Washington, lichens, along with algae, fungi, liverworts, and mosses, form a crust that covers and stabilizes dry soil, brings in nitrogen from the atmosphere, and provides nutrients for plant growth.

Besides their beauty, lichens are an important food source for caribou, deer, grouse, and wild turkeys and a nesting material for flying squirrels and other small mammals. Lichens are also a favored nesting material for at least 45 species of North American birds, including hummingbirds, kinglets, warblers, and flycatchers. They are also used by insects, spiders, snails, slugs, and other invertebrates for food or shelter.

Humans have a long association with lichens. First People in British Columbia favored wolf lichen as a source of yellow dye for baskets, wood, feathers, cloth, fur, and other items, while old man’s beard lichen was used for baby diapers. You can find abundant information about making your own lichen dyes online; we tried it with Evernia, which created a lovely purple dye for wool yarn.

Purple dye made from Evernia lichen. Lichens were placed in the jar with household ammonia and water and left to steep. The longer you let the mixture steep, the deeper the color becomes. Photo by Thomas Noland.

Scientists have long used lichens in another unique fashion: as biomonitors, or organisms that can tell us about the health of the environment. Lichens not only absorb water from the air, they are also subject to air-borne pollutants such as metals, sulfur dioxide, and fluorides. Some lichens are sensitive to the effects of pollution and can’t survive in areas with polluted air, while others can. By analyzing the community of lichens found in a given area, scientists can learn about the air quality in that area. The U.S. Forest Service has been collecting lichen data since the 1970s, using it, in their words, “to tell us how air pollution and climate are affecting the forested landscape and how we are doing as managers in mitigating changing atmospheric conditions and pollution.”

In some forests of Europe and the east coast of Canada, it appears that acid rain (a result of air pollution) has reduced the diversity of lichens compared to historical levels. We’re fortunate that species that require clean air and ancient trees still find refuge in places like Olympic National Park. On the coast of British Columbia, conifer trees still provide habitat for at least twelve species of lichens that only live on this type of tree.

Improvements in air quality over the past several decades have allowed lichens to start recovering in some cities that were once “lichen deserts” because of smog. In fact, some “urban lichens” survive and even thrive in the company of humans. Those lichens that tolerate air pollution tend to have surfaces that repel rainwater into little beads. Since they don’t absorb the water from their surfaces, they don’t absorb the air pollutants either.

In the Antarctic, where lichens are a dominant feature, scientists have proposed using them to monitor climate change. This is also being done for lichen communities in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California.

Lichen sculpture by David Eisenhour, photo by Ann Welch.

Even if you don’t go to visit ancient trees or make a trip to a native prairie to see lichens, we hope you’ll explore the lichens right next door. Over 30 lichen species are known to dwell in Seattle. In our suburban Everett backyard, we counted five species of lichens—three on a red alder tree (a crustose, a foliose, and a fruticose); a delicate cup lichen on a piece of driftwood that’s been in the garden for years; and a crustose orange lichen on, of all places, our natural gas meter. Lichens are an abundant and fascinating part of our lives.

Orange crustose lichen growing on natural gas meter, Everett, Washington. Photo by Thomas Noland.

Pixie cup lichen (Cladonia) growing on driftwood in a garden, Everett, Washington. Photo by Thomas Noland.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Katherine Glew, Associate Curator of the lichen collection at the University of Washington Herbarium and long-time friend, for her help reviewing this article and providing her list of “urban lichens” in Seattle.

Sara and Thomas Noland are naturalists who live in Everett, Washington. They live in a tiny house with many cats but are fortunate to have a big yard with lots of trees, birds, and lichens. They frequently take field trips to enjoy and photograph mountains, beaches, and deserts, as well as enjoying the creatures in their own neighborhood.

Table of Contents, Issue #5, Autumn 2019

Think Like a Mushroom

by David Ansley, Autumn 2019 Photos by John F. Williams, except where notedPhoto by John F. WilliamsBy David Ansley, Autumn 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedMushrooms? I don’t know how I missed them. I grew up deep in a second-growth...

Ghost Plant

AN UNDERSTORY THIEF by Adelia E. Ritchie, Autumn 2019 Photos by John F. Williams except where notedAN UNDERSTORY THIEF by Adelia E. Ritchie, Autumn 2019 Indian Pipes “Stop,” I said. “Indian Pipes.” Ghostly white, tiny vampires reaching up from moist loam...

Mushroom Poetry

by Mahathi Mangipudi, Autumn 2019 Photos by John F. Williams, except where notedBy Mahathi Mangipudi Autumn 2019 Photos by John F. Williams except where notedEquinox ~ s p r i n g ~fragile buds twist and turn,bloom under warm rays of pastel goldnutrients taken from...

Foto Tour 1

Showcase of Participant Photos from June 4, 2019 Showcase of Participant Photos from June 4, 2019 On June 4, 2019, WSU Extension in Kitsap County hosted a Forest Foto Expedition led by John F. Williams. We met at Newberry Hill Heritage Park in Silverdale. A park...

Mushroom Photo Essay

by John F. Williams, Autumn 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedBy John F. Williams, Autumn 2019 Photos & video by John F. Williams except where notedintroduction This issue contains a couple of very informative articles about mushrooms...

Survival of Our Woods

DEPENDS ON MUSHROOMS by Olaf K. Ribeiro, Autumn 2019DEPENDS ON MUSHROOMS by Olaf K. Ribeiro, Autumn 2019 Have you ever wondered about the mushrooms you see in the woods? Actually, there is much more to mushrooms than the colorful forms that so delight us during our...

Yellow Spotted Millipede

by Catherine Whalen, Autumn 2019A couple of yellow-spotted millipedes spotted in North Kitsap Heritage Park in May. Photo by John F. WilliamsA couple of yellow-spotted millipedes spotted in North Kitsap Heritage Park in May. Photo by John F. WilliamsBy Catherine...

More Mushrooms: Another Photo Essay

by Catherine Whalen, Autumn 2019 Photos & video by Catherine Whalen except where notedBy Catherine Whalen, Autumn 2019 Photos & video by Catherine Whalen except where notedart imitates lifeI found the above mushroom in my front yard one afternoon and it...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

FIND OUT MORE

Art

Photos of two lichen sculptures by David Eisenhour in this article. More of his sculptures of nature can be see on his web site: http://eisenhoursculpture.com/Portfolio.html

Books and reports:

- Lichens by Willam Purvis (Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000).

- Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest by Bruce McCune and Linda Geiser (Oregon State University Press, 2000).

- Mosses, Lichens, and Ferns of Northwest North America by Dale Vitt, Janet Marsh, and Robin Bovey (Lone Pine Publishing, 1988).

- Inventory of the Mosses, Liverworts, Hornworts, and Lichens of Olympic National Park, Washington: Species List by Martin Hutten, Andrea Woodward, and Karen Hutten (U.S. Geological Survey, 2005).

- Lichen Communities as Climate Indicators in the U.S. Pacific States by Robert Smith, Sarah Jovan, and Bruce McCune (U.S. Forest Service, 2017).

- The Natural History of Puget Sound Country by Arthur Kruckeberg (University of Washington Press, 1995).

- Seashore Life of the Northern Pacific Coast by Eugene Kozloff (University of Washington Press, 1983).

- Introduction to Microbiotic Crusts (Natural Resources Conservation Service, 1997).

Articles and papers:

- “Lichen Composition in Blue-gray Gnatcatcher and Ruby-throated Hummingbird Nests,” by Jim McCormac and Ray E. Showman, The Ohio Cardinal, Fall 2009 and Winter 2009-2010. https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/V33.1-2.OhioCardinal_Fall2009-Winter2009-2010_p72-82_Lichen%20Composition%20in%20Blue-gray%20Gnatcatcher%20and%20Roby-throated%20Hummingbird%20Nests.pdf

- “Freshwater and Marine Lichen-Forming Fungi,“ by D.L. Hawksworth, (2000), Fungal Diversity 5:1‑7. http://www.fungaldiversity.org/fdp/sfdp/FD_5_1-7.pdf

- “Lichenometric Dating of Historic Inscriptions on a Rock Outcrop in Coastal Oregon,” by Bruce McCune, Katherine Haramundanis, and Edward Gaposchkin (2019), Northwest Science 92(5): 388-394. https://bioone.org/journals/northwest-science/volume-92/issue-5/046.092.0507/Lichenometric-Dating-of-Historic-Inscriptions-on-a-Rock-Outcrop-in/10.3955/046.092.0507.full

- “Antarctic Studies Show Lichens to be Excellent Biomonitors of Climate Change,” by Leopoldo Sancho, Ana Pintado, and T.G. Allan Green, Diversity 2019: 11(3). https://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/11/3/42

- “Cyanolichens and Conifers: Implications for Global Conservation,” by Trevor Goward and André Arsenault, Forest, Snow, and Landscape Research 75, 3: 303–318 (2000). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228845405_Cyanolichens_and_conifers_Implications_for_global_conservation

- “Rare Inland Reindeer Lichens at Mima Mounds in Southwest Washington State,” by R.J. Smith and others, North American Fungi 7(3): 1-2 (2012). https://www.pnwfungi.org/index.php/pnwfungi/article/view/1110

- “A Checklist of Soil-Dwelling Bryophytes and Lichens of the South Puget Sound Prairies of Western Washington,” by Lalita Calabria and others, Evansia 32(1):30-41 (2015). https://bioone.org/journals/Evansia/volume-32/issue-1/079.032.0106/A-Checklist-of-Soil-Dwelling-Bryophytes-and-Lichens-of-the/10.1639/079.032.0106.short

- “A Cumulative Checklist for the Lichen-forming, Lichenicolous and Allied Fungi of the Continental United States and Canada, Version 22,” by Theodore Esslinger, 2018. https://www.ndsu.edu/pubweb/~esslinge/chcklst/chcklst7.htm

Web pages:

- S. Forest Service lichens page: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/beauty/lichens/index.shtml

- Smithsonian “Seaside Lichens” article: https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/seaside-lichens

- Northwest Lichenologists page: http://northwest-lichenologists.wildapricot.org/

- One of many web pages about creating dyes with lichens: https://blog.mycology.cornell.edu/2006/12/12/dyeing-with-lichens-mushrooms/

- S. Forest Service National Lichens and Air Quality Database and Clearinghouse: http://gis.nacse.org/lichenair/