FROM SWAMPS & BOGS TO MARSHES & MEADOWS

by Sara & Thomas Noland, Autumn 2020

Photos by Thomas Noland except as noted

FROM SWAMPS & BOGS TO MARSHES & MEADOWS

by Sara & Thomas Noland, Summer 2020

Photos by Thomas Noland except as noted

Wetlands are part of our landscape here in the lowlands near the Salish Sea. Anyone who’s walked around in a park or forest has probably spotted some familiar wetland signs: a pond where tree frogs chorus in the early spring, or a patch of skunk cabbage in a shady glade. But some kinds of wetlands might not even look like “wetlands” to the unpracticed eye, while others are rare and hard to find. All are worth a closer look and exploration.

Cattail photo by John F. Williams

In a wetland, water is present long enough during the growing season to favor certain kinds of plants. That water can appear as surface ponding or it can be below the surface of the soil, keeping the plants’ roots wet. Plants range widely in their ability to deal with being flooded or living in soggy soils. For example, common cattail needs to stay wet and is often found in permanent ponds. On the dry end of the spectrum, big-leaf maple does best in well-drained upland soils. Then there are all the species in the middle of the spectrum; those that like conditions somewhere in between wet and dry and can be found both within and outside of wetlands.

Many wetland plants have evolved to handle being in wet soils or even underwater for part of the year. For example, some willows grow special roots above the soil surface that allow them to survive even during extended flooding. Other species, such as Douglas spirea (a shrub), tolerate widely fluctuating water levels that would kill other plants. However, major changes in the water reaching a wetland can alter its plant community, sometimes drastically (as we’ll discuss for bogs).

Maple photo by John F. Williams

wetlands take many forms

This article explores the different types of wetlands found in our region. Our focus is on the types of plants commonly found in each wetland community and the animals you might see there. This is not intended to be a scientific description of wetland types or categories (you can find those in other articles in this issue), but rather a general guide. Keep in mind that different types of wetlands often occur together, creating a mosaic of communities. Also, wetlands change over time, such as when a beaver dam blocks a stream, flooding a forested swamp; the trees eventually die and the forested swamp becomes a pond. Over many years the pond fills with sediment, allowing a shrub wetland to grow in. And so on.

freshwater ponds

Ponds have cattails, sedges, rushes, and even lily pads interspersed with areas of open water. Ponds that have year-round water might support fish such as bass. If the water is still, you will likely find a green layer of duckweed floating on the surface. Waterfowl, from ducks and coots to mergansers, use ponds as nesting spots or places to grab a quick bite along their migratory routes. In late winter, you can often find the egg masses of frogs or salamanders along the shallow margins of a pond, attached to a twig or reed. Dragonflies lay their eggs in ponds, and their larvae mature underwater until emerging as winged adults.

Shrubs such as Douglas spirea and willow may grow around the edge of a pond where the water is shallower. This fringing vegetation provides perches for dragonflies and birds, such as cedar waxwing, that swoop out to capture flying insects over the water. A pond wouldn’t be complete without a great blue heron stalking around its edges.

forested swamps

When you hear the word “swamp” you might think of mossy cypress trees of the South where alligators and water moccasins roam. We have forested swamps in Puget Sound as well, with western red cedar, red alder, Sitka spruce, and black cottonwood being common trees.

See the article about red alders in Issue #8

See the article about red alders in Issue #8

It’s not unusual to find a stream meandering through the wetland. For the hiker, forested swamps can be hard to navigate, with pockets of deep, wet soils interspersed with higher hummocks. If you can find one, a boardwalk trail is an ideal pathway through this type of wetland. This terrain creates a unique mosaic where water-lovers, such as skunk cabbage, can be neighbors with upland species like western hemlock.

The dense vegetation of the forest can make it hard to spot wildlife, but you might see or hear signs of deer, racoons, owls, woodpeckers, coyotes, and many other species taking advantage of the hiding places and food sources available in the swamp.

shrub wetlands

Shrub wetlands are dominated by woody plants (shrubs) such as Douglas spirea, red osier dogwood, salmonberry, and willows. Sometimes the shrubs form such dense thickets that nothing can grow underneath. Douglas spirea has bright pink, fluffy blooms in mid-summer.

A shrub wetland might be found in the midst of a forested swamp where the trees have died, creating a sunny area where shrubs can establish. Or the shrubs might border a stream, pond, lake, or emergent wetland. Shrubs are excellent bird habitat, providing perches, nesting places, food, and cover, as well as browse for deer, and food and building materials for beavers.

emergent wetlands

Emergent wetlands lack shrubs or trees, and they are instead dominated by grasses, sedges, rushes, and other ground cover species that “emerge” or poke up from the water. Unlike duckweed, which floats, these plants are rooted in the soil. This type of wetland usually has seasonal flooding in winter and spring, with wet soils but little surface water by summer. A good place to find them is in river floodplains, as well as pastures and ungrazed meadows. Some of the emergent plants, such as creeping buttercup, are widespread and can be found in backyards as well as wetlands. Others, such as spikerush, are particular to wetlands.

The diversity of plants in an emergent wetland can be amazing if you look closely at the seeming tangle of green herbs. The saying “rushes are round and sedges have edges” is good to keep in mind when identifying emergent wetland species. You might find tiny plants such as American brooklime with delicate flowers. Depending on the season, an emergent wetland might support ducks dabbling in early spring ponds, or deer browsing on tender summer grass, or swallows hunting a swarm of insects.

salt marshes

Salt marshes are wetlands along the shores of Puget Sound where the water is saline enough to affect the types of plants that can grow there. In many places a stream or river flows through the marsh into the Sound, diluting the salt and making the water brackish. This is sometimes called an estuarine marsh or marine marsh.

In addition to salinity, the plants of a salt marsh live with the rising and falling of the tide, and each species has a preference for how much salt and how much inundation it can tolerate. For example, some species, such as Puget gumweed and Pacific silverweed, tolerate salt spray but not much tidal inundation; they grow at higher elevations in the marsh. Others, such as Lyngby’s sedge, grow at lower elevations and prefer brackish water.

Other common salt marsh species include pickleweed, fleshy jaumea, fat hen, saltgrass, and seaside plantain. Salt marshes are incredibly important for fish and wildlife, from creatures living in the mud, to young salmon finding a refuge, to bald eagles and great blue herons.

bogs

Bogs form when layers of sphagnum moss grow and die, year after year, creating deep peat soils. They often form in potholes left by the glaciers. The very acidic conditions in a bog support a unique community of plants and animals. These include carnivorous plants, like sundew, that attract and then digest insects to supplement their diet. Other common bog plants include Labrador tea (in the rhododendron family), bog cranberry, sedges, and bog laurel.

Rare plant species and insects, along with more common wildlife, inhabit bogs. Bogs themselves are very rare in our region today. Some were mined for peat and are now open water lakes. Others have been used as discharge points for stormwater, changing their water supply and chemistry so much that the plant communities have been altered.

According to the Washington Department of Ecology, once a bog has been lost it can’t be recreated. The good news is, some remaining bogs have been protected in natural area preserves and other set-aside areas. For more details about local bogs, see King County’s web site.

Sara and Thomas Noland are naturalists who live in Everett, Washington. They live in a tiny house with many cats but are fortunate to have a big yard with lots of trees, birds, and lichens. They frequently take field trips to enjoy and photograph mountains, beaches, and deserts, as well as enjoying the creatures in their own neighborhood.

Table of Contents, Issue #9, Autumn 2020

Issue 9 Art Poetry

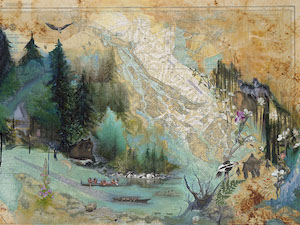

Autumn 2020Juan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaJuan de Fuca painting by Melissa McCannaSummer 2020Going Home, painting by Julia MillerComing Home by Dawn Henthorn Salmon come home home to the Elwha. Bit by bit of rubble two feet at a time, the dams were removed,...

Salt Marshes

by Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020Gumweed photo by John F. WilliamsGumweed photo by John F. Williamsby Ron Hirschi, Autumn 2020I’ve enjoyed, studied, mapped, and tried to protect wet places for pretty much my entire life. So, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share some...

Importance of Wetlands

by Josh Wozniak, Autumn 2020 Photographs by John F. Williamsby Josh Wozniak, Summer 2020 Photographs by John F. WilliamsTaking many forms, wetlands are natural features of the landscape that provide crucial functions for both nature and humankind. We benefit directly...

Newts: Wetland Magicians

by Sharon & Paul Pegany, Autumn 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany except as notedby Sharon & Paul Pegany, Summer 2020 Photos by Sharon Pegany, except as noted. Did I just see what I think I saw? I had to do a double take while exploring the edge of a local pond...

Healthy Wetlands

by Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Autumn 2020Wetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. WilliamsWetland at Point No Point, photo by John F. Williamsby Curt Hart and Marcus Humberg, Summer 2020For the 4.2 million residents in and around Puget Sound, there is a good...

Earthquakes and Tsunamis

by Carrie Garrison-Laney and Ian Miller Autumn 2020 A photo of sediments in the coastal marsh near the mouth of Salt Creek on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, showing distinct bands of different colors and textures. Photo by Ian Miller.A photo of sediments in the coastal...

10 Things About Duckweed

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as notedby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020 Photos by John F. Williams, except as noted1. Duckweed grows in dense colonies in quiet water that is undisturbed by wave action. We try to avoid insulting still...

Carpenter Creek Salt Marsh

by Melissa Fleming & Terry Pereida, Autumn 2020 Photos by Terry Pereida, except as notedSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom TwiggSalt marsh with the main channel running down the middle. Photo by Tom Twiggby Melissa Fleming &...

Wetland Basics

Frank Stricklin, Autumn 2020 Photos by John F. Williams except as notedThis large wetland in Newberry Hill Heritage Park is listed by the State of Washington as a “wetland of significant conservation value.” It contains many species of aquatic plants, and some...

Blue Carbon

by Adelia Ritchie, Autumn 2020Underwater Rainbow, painting by Julia MillerUnderwater Rainbow, painting by Julia Millerby Adelia Ritchie, Summer 2020As you’ll see everywhere else in this issue, a wetland system isn’t just another lovely place for a nature walk. Wetland...

PLEASE HELP SUPPORT

SALISH MAGAZINE

DONATE

Salish Magazine contains no advertising and is free. Your donation is one big way you can help us inspire people with stories about things that they can see outdoors in our Salish Sea region.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.

We also don't advertise Salish Magazine, so please spread the word of this online resource to your friends and colleagues.

Thanks so much for your interest and your support.